Creating a GraphQL Server with Node.js and MongoDB

This article was peer reviewed by Ryan Chenkie. Thanks to all of SitePoint’s peer reviewers for making SitePoint content the best it can be!

Requesting data from the server on the client side is not a new concept. It allows an application to load data without having to refresh the page. This is most used in single page applications, which instead of getting a rendered page from the server, request only the data needed to render it on the client side.

The most common approach across the web in the last few years has been the REST architectural style. However, this approach brings some limitations for high data demand applications. In a RESTful system, we need to make multiple HTTP requests to grab all the data we want, which has a significant performance impact. What if there was a way to request multiple resources in a single HTTP request?

Introducing GraphQL, a query language which unifies the communication between client and server side. It allows the client side to describe exactly the data it needs, in a single request.

In this article, we’ll create a Node.js/Express server with a GraphQL route which will handle all our queries and mutations. We’ll then test this route by sending some POST requests and analyze the outcome using Postman.

You can find the full source code for this application here. I’ve also made a Postman collection that you can download here.

Setting up a GraphQL Endpoint on an Express Server

First thing to do is create our Node.js server using the Express framework. We’ll also use MongoDB together with Mongoose for data persistency, and babel to use ES6. Since the code is transpiled to ES5 at runtime, there is no need for a build process. This is done in the index.js:

// index.js

require('babel/register');

require('./app');

In app.js we’ll start our server, connect with a Mongo database and create a GraphQL route.

// app.js

import express from 'express';

import graphqlHTTP from 'express-graphql';

import mongoose from 'mongoose';

import schema from './graphql';

var app = express();

// GraphqQL server route

app.use('/graphql', graphqlHTTP(req => ({

schema,

pretty: true

})));

// Connect mongo database

mongoose.connect('mongodb://localhost/graphql');

// start server

var server = app.listen(8080, () => {

console.log('Listening at port', server.address().port);

});

The most relative part of the code above, in this article context, is where we define our GraphQL route. We use express-graphql, an Express middleware developed by Facebook’s GraphQL team. This will process the HTTP request through GraphQL and return the JSON response. For this to work we need to pass through in the options our GraphQL Schema which is discussed in the next section. We’re also setting the option pretty to true. This makes the JSON responses pretty-printed, making them easier to read.

GraphQL schema

For GraphQL to understand our requests we need to define a schema. And a GraphQL schema is nothing else than a group of queries and mutations. You can think of queries as resources to retrieve from the database and mutations as any kind of update to your database. We’ll create as an example a BlogPost and a Comment Mongoose model, and we will then create some queries and mutations for it.

Mongoose Models

Let’s start by creating the mongoose models. Won’t go into much detail here since mongoose isn’t the focus of this article. You can find the two models in models/blog-post.js and models/comment.js.

GraphQL Types

Like with Mongoose, in GraphQL we need to define our data structure. The difference is that we define for each query and mutation what type of data can enter and what is sent in the response. If these types don’t match, an error is thrown. Although it can seem redundant, since we’ve already defined a schema model in mongoose, it has great advantages, such as:

- You control what is allowed in, which improves your system security

- You control what is allowed out. This means you can define specific fields to never be allowed to be retrieved. For example: passwords or other sensitive data

- It filters invalid requests so that no further processing is taken, which can improve the server’s performance

You can find the source code for the GraphQL types in graphql/types/. Here’s an example of one:

// graphql/types/blog-post.js

import {

GraphQLObjectType,

GraphQLNonNull,

GraphQLString,

GraphQLID

} from 'graphql';

export default new GraphQLObjectType({

name: 'BlogPost',

fields: {

_id: {

type: new GraphQLNonNull(GraphQLID)

},

title: {

type: GraphQLString

},

description: {

type: GraphQLString

}

}

});

Here, we’re defining the blog post output GraphQL type, which we’ll use further when creating the queries and mutations. Note how similar the structure is to the mongoose model BlogPost. It can seem duplication of work, but these are separated concerns. The mongoose model defines the data structure for the database, the GraphQL type defines a rule of what is accepted in a query or mutation to your server.

GraphQL Schema Creation

With the Mongoose models and the GraphQL types created we can now create our GraphQL schema.

// graphql/index.js

import {

GraphQLObjectType,

GraphQLSchema

} from 'graphql';

import mutations from './mutations';

import queries from './queries';

export default new GraphQLSchema({

query: new GraphQLObjectType({

name: 'Query',

fields: queries

}),

mutation: new GraphQLObjectType({

name: 'Mutation',

fields: mutations

})

});

Here we export a GraphQLSchema where we define two properties: query and mutation. A GraphQLObjectType is one of the many GraphQL types. With this one in particular you can specify:

- name – which should be unique and identifies the object;

- fields – property which accepts an object than in this case will be our queries and mutations.

We’re importing queries and mutations from another location, this is only for structural purposes. The source code is structured in a way that enables our project to scale well if we want to add more models, queries, mutations, etc.

The queries and mutations variables that we’re passing through to fields are plain JavaScript objects. The keys are the mutation or query names. The values are plain JavaScript objects with a configuration that tells GraphQL what to do with them. Let’s take the following GraphQL query as an example:

query {

blogPosts {

_id,

title

}

comments {

text

}

}

For GrahpQL to understand what to do with this query we need to define the blogPosts and comments query. So our queries variable would be something like this:

{

blogPosts: {...},

comments: {...}

}

Same goes for mutations. This to explain that there is a direct relation between the keys we have in our queries or mutations and the names we put in the queries. Let’s now see how each of these queries and mutations are defined.

Queries

Starting from the queries, let’s pick up from an example using the models we’ve created so far. A good example can be to get a blog post and all its comments.

In a REST solution you’d have to make two HTTP requests for this. One to get the blog post and the other to get the comments, which would look something like this:

GET /api/blog-post/[some-blog-post-id]

GET /api/comments?postId='[some-blog-post-id]'

In GraphQL we can make this in only one HTTP request, with the following query:

query ($postId: ID!) {

blogPost (id: $postId) {

title,

description

}

comments (postId: $postId) {

text

}

}

We can fetch all the data we want in one single request, which alone improves performance. We can also ask for the exact properties we’re going to use. In the example above, the response will only bring the title and description of the blog post, and the comments will only bring the text.

Retrieving only the needed fields from each resource, can have massive impact on the loading time of a web page or application. Let’s see for example the comments, which also have a _id and a postId properties. Each one of these are small, 12 bytes each to be exact (not counting with the object key). This has little impact when it is a single or a few comments. When we’re talking about let’s say 200 comments, that’s over 4800 bytes that we won’t even use. And that can make a significant difference on the application loading time. This is specially important for devices with limited resources, such as mobile ones, which usually have a slower network connection.

For this to work we need to tell GraphQL how to fetch the data for each specific query. Let’s see an example of a query definition:

// graphql/queries/blog-post/single.js

import {

GraphQLList,

GraphQLID,

GraphQLNonNull

} from 'graphql';

import {Types} from 'mongoose';

import blogPostType from '../../types/blog-post';

import getProjection from '../../get-projection';

import BlogPostModel from '../../../models/blog-post';

export default {

type: blogPostType,

args: {

id: {

name: 'id',

type: new GraphQLNonNull(GraphQLID)

}

},

resolve (root, params, options) {

const projection = getProjection(options.fieldASTs[0]);

return BlogPostModel

.findById(params.id)

.select(projection)

.exec();

}

};

Here we’re creating a query that retrieves a single blog post based on an id parameter. Note that we’re specifying a type, which we previously created, that validates the output of the query. We’re also setting an args object with the needed arguments for this query. And finally, a resolve function where we query the database and return the data.

To further optimize the process of fetching data and leverage the projection feature on mongoDB, we’re processing the AST that GraphQL provide us to generate a projection compatible with mongoose. So if we make the following query:

query ($postId: ID!) {

blogPost (id: $postId) {

title,

description

}

}

Since we just need to fetch title and description from the database, the getProjection function will generate a mongoose valid projection:

{

title: 1,

description: 1

}

You can see other queries at graphql/queries/* in the source code. We won’t go through each one since they are all similar to the example above.

Mutations

Mutations are operations that will deal some kind of change in the database. Like queries we can group different mutations in a single HTTP request. Usually an action is isolated, such as ‘add a comment’ or ‘create a blog post’. Although, with the rising complexity of applications and data collection, being for analytics, user experience testing or complex operations, a user action on a website or application can trigger a considerable number of mutations to different resources of your database. Following our example, a new comment on our blog post can mean a new comment and an update to the blog post comments count. In a REST solution you would have something like the following:

POST /api/blog-post/increment-comment

POST /api/comment/new

With GraphQL you can do it in only one HTTP request with something like the following:

mutation ($postId: ID!, $comment: String!) {

blogPostCommentInc (id: $postId)

addComment (postId: $postId, comment: $comment) {

_id

}

}

Note that the syntax for the queries and mutations is exactly the same, only changing query to mutation. We can ask data from a mutation the same way we do from a query. By not specifying a fragment, like we have in the query above for the blogPostCommentInc, we’re just asking a true or false return value, which often is enough to confirm the operation. Or we can ask for some data like we have for addComment mutation, which can be useful to retrieve data generated on the server only.

Let’s then define our mutations in our server. Mutations are created exactly as a query:

// graphql/mutations/blog-post/add.js

import {

GraphQLNonNull,

GraphQLBoolean

} from 'graphql';

import blogPostInputType from '../../types/blog-post-input';

import BlogPostModel from '../../../models/blog-post';

export default {

type: GraphQLBoolean,

args: {

data: {

name: 'data',

type: new GraphQLNonNull(blogPostInputType)

}

},

async resolve (root, params, options) {

const blogPostModel = new BlogPostModel(params.data);

const newBlogPost = await blogPostModel.save();

if (!newBlogPost) {

throw new Error('Error adding new blog post');

}

return true;

}

};

This mutation will add a new blog post and return true if successful. Note how in type, we specify what is going to be returned. In args the arguments received from the mutation. And a resolve() function exactly as in a query definition.

Testing the GraphQL Endpoint

Now that we’ve created our Express server with a GraphQL route and some queries and mutations, let’s test it out by sending some requests to it.

There are a lot of ways to send GET or POST requests over to a location, such as:

- The Browser – by typing a url in your browser you’re sending a GET request. This has the limitation of not being able to send POST requests

- cURL – for command line fans. It enables to send any type of request to a server. Although, it isn’t the best interface, you can’t save requests and you need to write everything in a command line, which is not ideal from my point of view

- GraphiQL – a great solution for GraphQL. It’s an in browser IDE which you can use to create queries to your server. It has some great features such as: syntax highlighting and type ahead

There are more solutions than the ones described above. The first two are the most known and used ones. GraphiQL is the GraphQL team’s solution to simplify the process with GraphQL, since queries can be more complex to write.

From these three I’d recommend GraphiQL, although I prefer and recommend above all Postman. This tool is definitely an advance in API testing. It provides an intuitive interface where you can create and save collections of any type of request. You can even create tests for your API and run them with the click of a button. It also has a collaborative feature and enables to share collections of requests. So I’ve created one that you can download here, which you can then import to Postman. If you don’t have Postman installed, I definitely recommend you to do so.

Let’s start by running the server. You should have node 4 or higher installed; If you haven’t, I recommend using nvm to install it. We can then run the following in the command line:

$ git clone https://github.com/sitepoint-editors/graphql-nodejs.git

$ cd graphql-nodejs

$ npm install

$ npm start

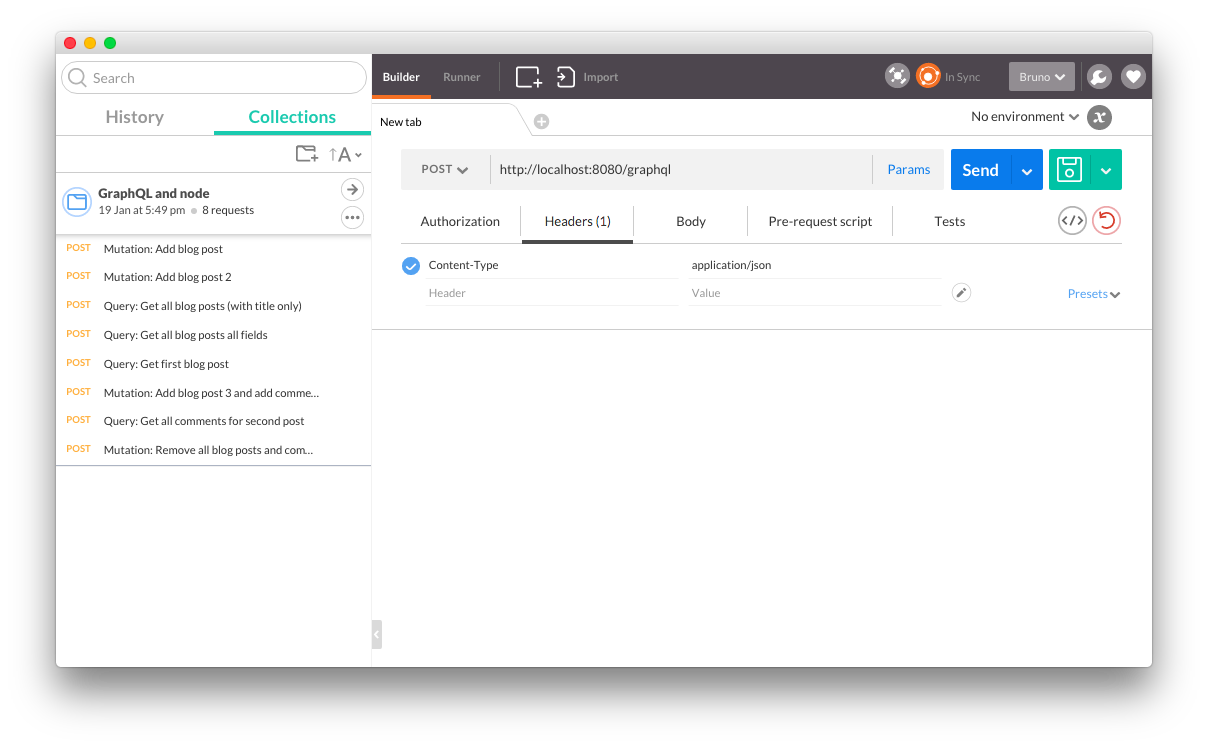

The server is now ready to receive requests, so let’s create some on Postman. Our GraphQL route is set on /graphql so first thing to do is setting the location to where we want to direct our request which is http://localhost:8080/graphql. We then need to specify if it is a GET or a POST request. Although you can use either of these, I prefer POST as it doesn’t affect the URL, making it cleaner. We also need to configure the header that goes with the request, in our case we just need to add Content-Type equal to application/json. Here’s how it looks all set up in Postman:

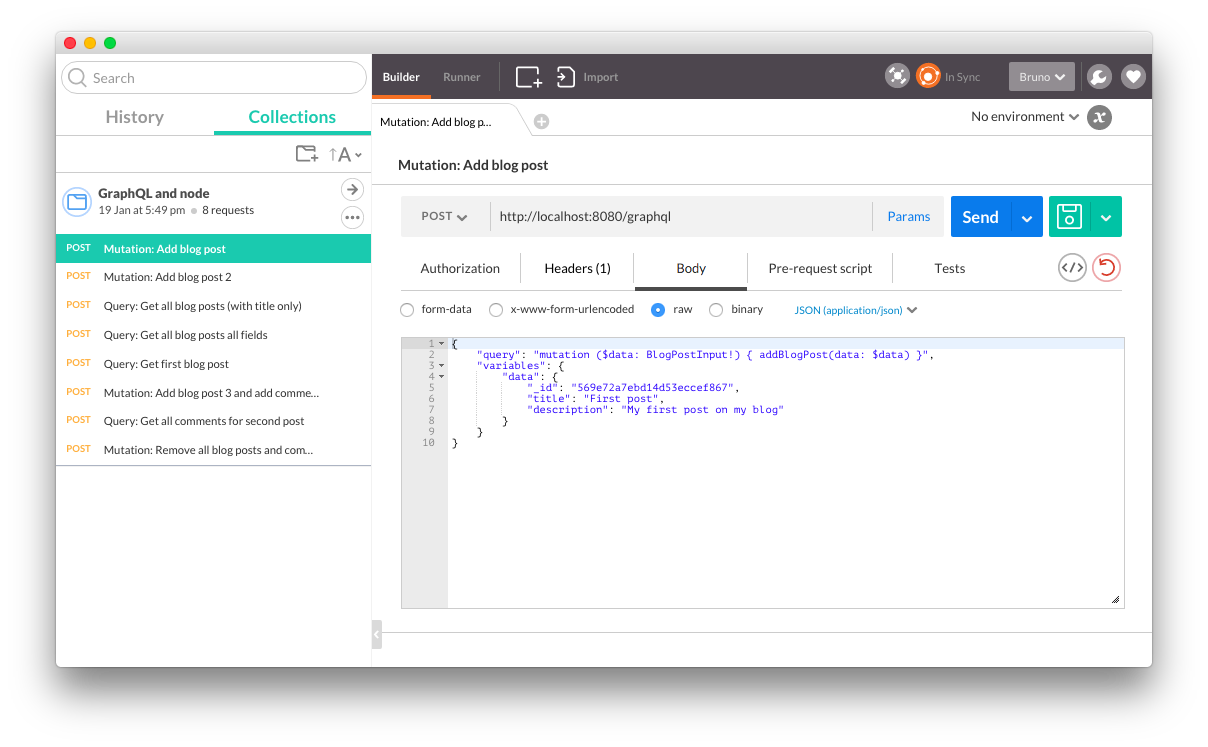

We can now create the body which will have our GraphQL query and variables needed in a JSON format like the following:

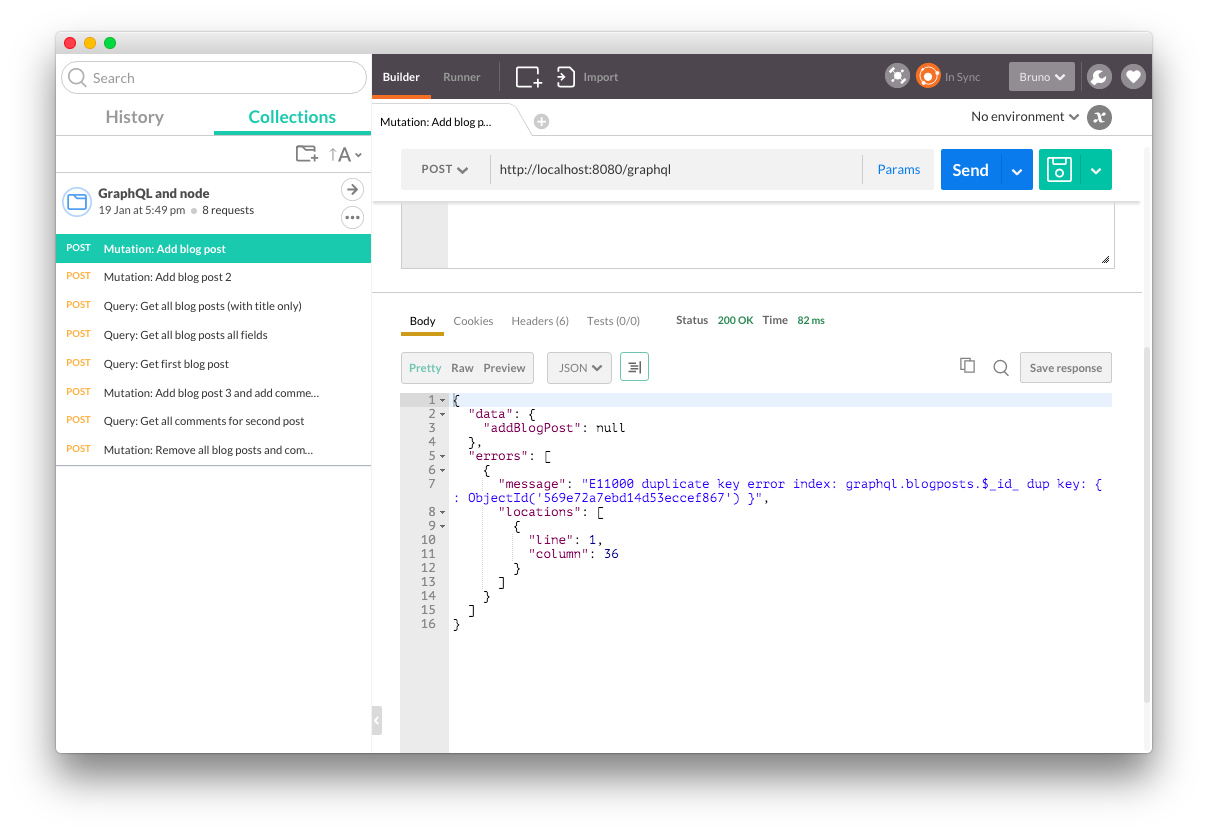

Assuming you’ve imported the collection I’ve supplied, you should already have some query and mutation requests that you can test. Since I’ve used hard-coded Mongo ids, run the requests in order and they should all succeed. Analyze what I’ve put in each one’s body and you’ll see it is just an application of what has been discussed in this article. Also, if you run the first request more than once, since it will be a duplicate id you can see how errors are returned:

Conclusion

In this article, we’ve introduced the potential of GraphQL and how it differs from a REST architectural style. This new query language is set to make a great impact on the web. Especially for more complex data applications, that can now describe exactly the data they want and request it with a single HTTP request.

I’d love to hear from you: what do you think of GraphQL and what has been your experience with it?