Arrow Functions in JavaScript: How to Use Fat & Concise Syntax

Learn all about JavaScript arrow functions. We’ll show you how to use ES6 arrow syntax, and some of the common mistakes you need to be aware of when leveraging arrow functions in your code. You’ll see lots of examples that illustrate how they work.

JavaScript arrow functions arrived with the release of ECMAScript 2015, also known as ES6. Because of their concise syntax and handling of the this keyword, arrow functions quickly became a favorite feature among developers.

Arrow Function Syntax: Rewriting a Regular Function

Functions are like recipes where you store useful instructions to accomplish something you need to happen in your program, like performing an action or returning a value. By calling your function, you execute the steps included in your recipe. You can do so every time you call that function without needing to rewrite the recipe again and again.

Here’s a standard way to declare a function and then call it in JavaScript:

// function declaration

function sayHiStranger() {

return 'Hi, stranger!'

}

// call the function

sayHiStranger()

You can also write the same function as a function expression, like this:

const sayHiStranger = function () {

return 'Hi, stranger!'

}

JavaScript arrow functions are always expressions. Here’s how you could rewrite the function above as an arrow function expression using the fat arrow notation:

const sayHiStranger = () => 'Hi, stranger'

The benefits of this include:

- just one line of code

- no

functionkeyword - no

returnkeyword - and no curly braces {}

In JavaScript, functions are “first-class citizens.” You can store functions in variables, pass them to other functions as arguments, and return them from other functions as values. You can do all of these using JavaScript arrow functions.

The Parens-free Syntax

In the above example, the function has no parameters. In this case, you must add a set of empty parentheses () before the fat arrow (=>) symbol. The same holds when you create functions that have more than one parameter:

const getNetflixSeries = (seriesName, releaseDate) => `The ${seriesName} series was released in ${releaseDate}`

// call the function

console.log(getNetflixSeries('Bridgerton', '2020') )

// output: The Bridgerton series was released in 2020

With just one parameter, however, you can go ahead and leave out the parentheses (you don’t have to, but you can):

const favoriteSeries = seriesName => seriesName === "Bridgerton" ? "Let's watch it" : "Let's go out"

// call the function

console.log(favoriteSeries("Bridgerton"))

// output: "Let's watch it"

Be careful, though. If, for example, you decide to use a default parameter, you must wrap it inside parentheses:

// with parentheses: correct

const bestNetflixSeries = (seriesName = "Bridgerton") => `${seriesName} is the best`

// outputs: "Bridgerton is the best"

console.log(bestNetflixSeries())

// no parentheses: error

const bestNetflixSeries = seriesName = "Bridgerton" => `${seriesName} is the best`

// Uncaught SyntaxError: invalid arrow-function arguments (parentheses around the arrow-function may help)

And just because you can, doesn’t mean you should. Mixed with a little bit of light-hearted, well-meaning sarcasm, Kyle Simpson (of You Don’t Know JS fame) has put his thoughts on omitting parentheses into this flow chart.

Implicit Return

When you only have one expression in your function body, you can make ES6 arrow syntax even more concise. You can keep everything on one line, remove the curly braces, and do away with the return keyword.

You’ve just seen how these nifty one-liners work in the examples above. Here’s one more example, just for good measure. The orderByLikes() function does what it says on the tin: that is, it returns an array of Netflix series objects ordered by the highest number of likes:

// using the JS sort() function to sort the titles in descending order

// according to the number of likes (more likes at the top, fewer at the bottom

const orderByLikes = netflixSeries.sort( (a, b) => b.likes - a.likes )

// call the function

// output:the titles and the n. of likes in descending order

console.log(orderByLikes)

This is cool, but keep an eye on your code’s readability — especially when sequencing a bunch of arrow functions using one-liners and the parentheses-free ES6 arrow syntax, like in this example:

const greeter = greeting => name => `${greeting}, ${name}!`

What’s going on there? Try using the regular function syntax:

function greeter(greeting) {

return function(name) {

return `${greeting}, ${name}!`

}

}

Now, you can quickly see how the outer function greeter has a parameter, greeting, and returns an anonymous function. This inner function in its turn has a parameter called name and returns a string using the value of both greeting and name. Here’s how you can call the function:

const myGreet = greeter('Good morning')

console.log( myGreet('Mary') )

// output:

"Good morning, Mary!"

Watch Out for these Implicit Return Mistakes

When your JavaScript arrow function contains more than one statement, you need to wrap all of them in curly braces and use the return keyword.

In the code below, the function builds an object containing the title and summary of a few Netflix series (Netflix reviews are from the Rotten Tomatoes website) :

const seriesList = netflixSeries.map( series => {

const container = {}

container.title = series.name

container.summary = series.summary

// explicit return

return container

} )

The arrow function inside the .map() function develops over a series of statements, at the end of which it returns an object. This makes using curly braces around the body of the function unavoidable.

Also, as you’re using curly braces, an implicit return is not an option. You must use the return keyword.

If your function returns an object literal using the implicit return, you need to wrap the object inside round parentheses. Not doing so will result in an error, because the JavaScript engine mistakenly parses the object literal’s curly braces as the function’s curly braces. And as you’ve just noticed above, when you use curly braces in an arrow function, you can’t omit the return keyword.

The shorter version of the previous code demonstrates this syntax:

// Uncaught SyntaxError: unexpected token: ':'

const seriesList = netflixSeries.map(series => { title: series.name });

// Works fine

const seriesList = netflixSeries.map(series => ({ title: series.name }));

You Can’t Name Arrow Functions

Functions that don’t have a name identifier between the function keyword and the parameter list are called anonymous functions. Here’s what a regular anonymous function expression looks like:

const anonymous = function() {

return 'You can\'t identify me!'

}

Arrow functions are all anonymous functions:

const anonymousArrowFunc = () => 'You can\'t identify me!'

As of ES6, variables and methods can infer the name of an anonymous function from its syntactic position, using its name property. This makes it possible to identify the function when inspecting its value or reporting an error.

Check this out using anonymousArrowFunc:

console.log(anonymousArrowFunc.name)

// output: "anonymousArrowFunc"

Be aware that this inferred name property only exists when the anonymous function is assigned to a variable, as in the examples above. If you use an anonymous function as a callback, you lose this useful feature. This is exemplified in the demo below where the anonymous function inside the .setInterval() method can’t avail itself of the name property:

let counter = 5

let countDown = setInterval(() => {

console.log(counter)

counter--

if (counter === 0) {

console.log("I have no name!!")

clearInterval(countDown)

}

}, 1000)

And that’s not all. This inferred name property still doesn’t work as a proper identifier that you can use to refer to the function from inside itself — such as for recursion, unbinding events, etc.

The intrinsic anonymity of arrow functions has led Kyle Simpson to express his view on them as follows:

Since I don’t think anonymous functions are a good idea to use frequently in your programs, I’m not a fan of using the

=>arrow function form. — You Don’t Know JS

How Arrow Functions Handle the this Keyword

The most important thing to remember about arrow functions is the way they handle the this keyword. In particular, the this keyword inside an arrow function doesn’t get rebound.

To illustrate what this means, check out the demo below:

[codepen_embed height=”300″ default_tab=”html,result” slug_hash=”qBqgBmR” user=”SitePoint”]See the Pen

JS this in arrow functions by SitePoint (@SitePoint)

on CodePen.[/codepen_embed]

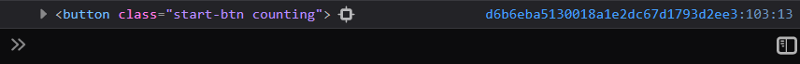

Here’s a button. Clicking the button triggers a reverse counter from 5 to 1, which displays on the button itself.

<button class="start-btn">Start Counter</button>

...

const startBtn = document.querySelector(".start-btn");

startBtn.addEventListener('click', function() {

this.classList.add('counting')

let counter = 5;

const timer = setInterval(() => {

this.textContent = counter

counter --

if(counter < 0) {

this.textContent = 'THE END!'

this.classList.remove('counting')

clearInterval(timer)

}

}, 1000)

})

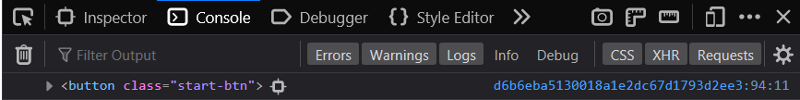

Notice how the event handler inside the .addEventListener() method is a regular anonymous function expression, not an arrow function. Why? If you log this inside the function, you’ll see that it references the button element to which the listener has been attached, which is exactly what’s expected and what’s needed for the program to work as planned:

startBtn.addEventListener('click', function() {

console.log(this)

...

})

Here’s what it looks like in the Firefox developer tools console:

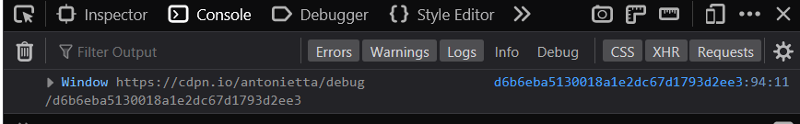

However, try replacing the regular function with an arrow function, like this:

startBtn.addEventListener('click', () => {

console.log(this)

...

})

Now, this doesn’t reference the button anymore. Instead, it references the Window object:

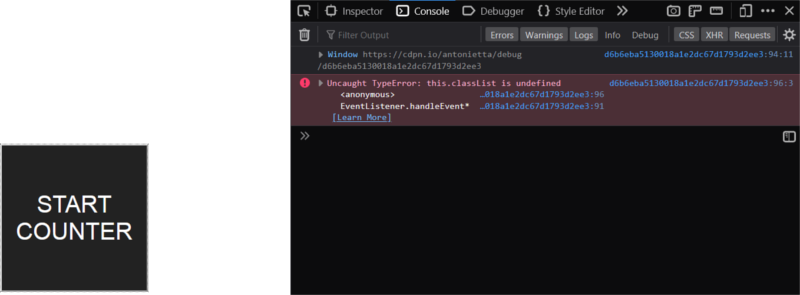

This means that, if you want to use this to add a class to the button after it’s clicked, your code won’t work, as shown in the folowing exampple:

// change button's border's appearance

this.classList.add('counting')

Here’s the error message in the console:

When you use an arrow function in JavaScript, the value of the this keyword doesn’t get rebound. It’s inherited from the parent scope (this is called lexical scoping). In this particular case, the arrow function in question is being passed as an argument to the startBtn.addEventListener() method, which is in the global scope. Consequently, the this inside the function handler is also bound to the global scope — that is, to the Window object.

So, if you want this to reference the start button in the program, the correct approach is to use a regular function, not an arrow function.

Anonymous Arrow Functions

The next thing to notice in the demo above is the code inside the .setInterval() method. Here, too, you’ll find an anonymous function, but this time it’s an arrow function. Why?

Notice what the value of this would be if you used a regular function:

const timer = setInterval(function() {

console.log(this)

...

}, 1000)

Would it be the button element? Not at all. It would be the Window object!

In fact, the context has changed, since this is now inside an unbound or global function which is being passed as an argument to .setInterval(). Therefore, the value of the this keyword has also changed, as it’s now bound to the global scope.

A common hack in this situation has been that of including another variable to store the value of the this keyword so that it keeps referring to the expected element — in this case, the button element:

const that = this

const timer = setInterval(function() {

console.log(that)

...

}, 1000)

You can also use .bind() to solve the problem:

const timer = setInterval(function() {

console.log(this)

...

}.bind(this), 1000)

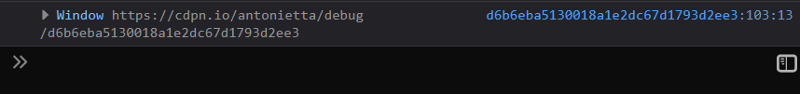

With arrow functions, the problem disappears altogether. Here’s what the value of this is when you use an arrow function:

const timer = setInterval( () => {

console.log(this)

...

}, 1000)

This time, the console logs the button, which is what we want. In fact, the program is going to change the button text, so it needs this to refer to the button element:

const timer = setInterval( () => {

console.log(this)

// the button's text displays the timer value

this.textContent = counter

}, 1000)

Arrow functions don’t have their own this context. They inherit the value of this from the parent, and it’s because of this feature that they make a great choice in situations like the one above.

JavaScript Arrow Functions Aren’t Always the Right Tool for the Job

Arrow functions aren’t just a fancy new way of writing functions in JavaScript. They have their own limitations, which means there are cases when you don’t want to use one. The click handler in the previous demo is a case in point, but it’s not the only one. Let’s examine a few more.

Arrow Functions as Object Methods

Arrow functions don’t work well as methods on objects. Here’s an example.

Consider this netflixSeries object, which has some properties and a couple of methods. Calling console.log(netflixSeries.getLikes()) should print a message with the current number of likes, and calling console.log(netflixSeries.addLike()) should increase the number of likes by one and then print the new value with a thankyou message on the console:

const netflixSeries = {

title: 'After Life',

firstRealease: 2019,

likes: 5,

getLikes: () => `${this.title} has ${this.likes} likes`,

addLike: () => {

this.likes++

return `Thank you for liking ${this.title}, which now has ${this.likes} likes`

}

}

Instead, calling the .getLikes() method returns “undefined has NaN likes”, and calling the .addLike() method returns “Thank you for liking undefined, which now has NaN likes”. So, this.title and this.likes fail to reference the object’s properties title and likes respectively.

Once again, the problem lies with the lexical scoping of arrow functions. The this inside the object’s method is referencing the parent’s scope, which in this case is the Window object, not the parent itself — that is, not the netflixSeries object.

The solution, of course, is to use a regular function:

const netflixSeries = {

title: 'After Life',

firstRealease: 2019,

likes: 5,

getLikes() {

return `${this.title} has ${this.likes} likes`

},

addLike() {

this.likes++

return `Thank you for liking ${this.title}, which now has ${this.likes} likes`

}

}

// call the methods

console.log(netflixSeries.getLikes())

console.log(netflixSeries.addLike())

// output:

After Life has 5 likes

Thank you for liking After Life, which now has 6 likes

Arrow Functions With 3rd Party Libraries

Another gotcha to be aware of is that third-party libraries will often bind method calls so that the this value points to something useful.

For example, inside a jQuery event handler, this will give you access to the DOM element that the handler was bound to:

$('body').on('click', function() {

console.log(this)

})

// <body>

But if we use an arrow function — which, as we’ve seen, doesn’t have its own this context — we get unexpected results:

$('body').on('click', () =>{

console.log(this)

})

// Window

Here’s a further example using Vue:

new Vue({

el: app,

data: {

message: 'Hello, World!'

},

created: function() {

console.log(this.message);

}

})

// Hello, World!

Inside the created hook, this is bound to the Vue instance, so the “Hello, World!” message is displayed.

If we use an arrow function, however, this will point to the parent scope, which doesn’t have a message property:

new Vue({

el: app,

data: {

message: 'Hello, World!'

},

created: function() {

console.log(this.message);

}

})

// undefined

Arrow Functions Have No arguments Object

Sometimes, you might need to create a function with an indefinite number of parameters. For example, let’s say you want to create a function that lists your favorite Netflix series ordered by preference. However, you don’t know how many series you’re going to include just yet. JavaScript makes the arguments object available. This is an array-like object (not a full-blown array) that stores the values passed to the function when called.

Try to implement this functionality using an arrow function:

const listYourFavNetflixSeries = () => {

// we need to turn the arguments into a real array

// so we can use .map()

const favSeries = Array.from(arguments)

return favSeries.map( (series, i) => {

return `${series} is my #${i +1} favorite Netflix series`

} )

console.log(arguments)

}

console.log(listYourFavNetflixSeries('Bridgerton', 'Ozark', 'After Life'))

When you call the function, you’ll get the following error message: Uncaught ReferenceError: arguments is not defined. What this means is that the arguments object isn’t available inside arrow functions. In fact, replacing the arrow function with a regular function does the trick:

const listYourFavNetflixSeries = function() {

const favSeries = Array.from(arguments)

return favSeries.map( (series, i) => {

return `${series} is my #${i +1} favorite Netflix series`

} )

console.log(arguments)

}

console.log(listYourFavNetflixSeries('Bridgerton', 'Ozark', 'After Life'))

// output:

["Bridgerton is my #1 favorite Netflix series", "Ozark is my #2 favorite Netflix series", "After Life is my #3 favorite Netflix series"]

So, if you need the arguments object, you can’t use arrow functions.

But what if you really want to use an arrow function to replicate the same functionality? One thing you can do is use ES6 rest parameters (...). Here’s how you could rewrite your function:

const listYourFavNetflixSeries = (...seriesList) => {

return seriesList.map( (series, i) => {

return `${series} is my #${i +1} favorite Netflix series`

} )

}

Conclusion

By using arrow functions, you can write concise one-liners with implicit return and finally forget about old-time hacks to solve the binding of the this keyword in JavaScript. Arrow functions also work great with array methods like .map(), .sort(), .forEach(), .filter(), and .reduce(). But remember: arrow functions don’t replace regular JavaScript functions. Remember to use JavaScript arrow functions only when they’re the right tool for the job.

If you have any questions about arrow functions, or need any help getting them just right, I recommend you stop by SitePoint’s friendly forums. There there are lots of knowledgeable programmers ready to help.

FAQs About Arrow Functions in JavaScript

You can define an arrow function using the following syntax: (parameters) => expression. For example: (x, y) => x + y defines an arrow function that takes two parameters and returns their sum.

You can define an arrow function using the following syntax: (parameters) => expression. For example: (x, y) => x + y defines an arrow function that takes two parameters and returns their sum.

Arrow functions differ from regular functions in several ways:

They do not have their own this. Instead, they inherit the this value from the surrounding lexical scope.

Arrow functions cannot be used as constructors, meaning you can’t create instances of objects using new.

Arrow functions don’t have their own arguments object. Instead, they inherit the arguments from the enclosing scope.

Arrow functions are more concise and suitable for simple, one-line operations.

Arrow functions offer concise syntax, making your code more readable. They also help avoid issues with the binding of this, as they inherit the surrounding context. This can simplify certain coding patterns and reduce the need for workarounds like bind, apply, or call.

While arrow functions are useful for many scenarios, they might not be suitable for all situations. They are best suited for short, simple functions. For complex functions or functions that require their own this context, traditional functions might be more appropriate.

Arrow functions were introduced in ECMAScript 6 (ES6) and are supported by modern browsers and Node.js versions. They are widely used in modern JavaScript development.

Arrow functions cannot be used as constructors, don’t have their own arguments object, and are less suitable for methods requiring a dynamic this context. Additionally, their concise syntax might not be suitable for functions with multiple statements.

Yes, arrow functions can be used for methods in objects or classes. However, remember that arrow functions do not have their own this, so they might not behave as expected in methods that require a dynamic this context.

When returning an object literal directly from an arrow function, you need to wrap the object in parentheses to avoid confusion with the function block. For example: () => ({ key: value }).

Yes, if an arrow function takes a single parameter, you can omit the parentheses around the parameter. For example, x => x * 2 is a valid arrow function