A Practical Guide to Angular Directives

This article focuses on Angular directives — what are they, how to use them, and to build our own.

Directives are perhaps the most important bit of an Angular application, and if we think about it, the most-used Angular unit, the component, is actually a directive.

An Angular component isn’t more than a directive with a template. When we say that components are the building blocks of Angular applications, we’re actually saying that directives are the building blocks of Angular applications.

Basic overview

At the core, a directive is a function that executes whenever the Angular compiler finds it in the DOM. Angular directives are used to extend the power of the HTML by giving it new syntax. Each directive has a name — either one from the Angular predefined like ng-repeat, or a custom one which can be called anything. And each directive determines where it can be used: in an element, attribute, class or comment.

By default, from Angular versions 2 and onward, Angular directives are separated into three different types:

Components

As we saw earlier, components are just directives with templates. Under the hood, they use the directive API and give us a cleaner way to define them.

The other two directive types don’t have templates. Instead, they’re specifically tailored to DOM manipulation.

Attribute directives

Attribute directives manipulate the DOM by changing its behavior and appearance.

We use attribute directives to apply conditional style to elements, show or hide elements or dynamically change the behavior of a component according to a changing property.

Structural directives

These are specifically tailored to create and destroy DOM elements.

Some attribute directives — like hidden, which shows or hides an element — basically maintain the DOM as it is. But the structural Angular directives are much less DOM friendly, as they add or completely remove elements from the DOM. So, when using these, we have to be extra careful, since we’re actually changing the HTML structure.

Using the Existing Angular Directives

Using the existing directives in Angular is fairly easy, and if you’ve written an Angular application in the past, I’m pretty sure you’ve used them. The ngClass directive is a good example of an existing Angular attribute directive:

<p [ngClass]="{'blue'=true, 'yellow'=false}">

Angular Directives Are Cool!

</p>

<style>

.blue{color: blue}

.yellow{color: yellow}

</style>

So, by using the ngClass directive on the example below, we’re actually adding the blue class to our paragraph, and explicitly not adding the yellow one. Since we’re changing the appearance of a class, and not changing the actual HTML structure, this is clearly an attribute directive. But Angular also offers out-of-the-box structural directives, like the ngIf:

@Component({

selector: 'ng-if-simple',

template: `

<button (click)="show = !show">{{show ? 'hide' : 'show'}}</button>

show = {{show}}

<br>

<div *ngIf="show">Text to show</div>

`

})

class NgIfSimple {

show: boolean = true;

}

In this example, we use the ngIf directive to add or remove the text using a button. In this case, the HTML structure itself is affected, so it’s clearly a structural directive.

For a complete list of available Angular directives, we can check the official documentation.

As we saw, using Angular directives is quite simple. The real power of Angular directives comes with the ability to create our own. Angular provides a clean and simple API for creating custom directives, and that’s what we’ll be looking at in the following sections.

Creating an attribute directive

Creating a directive is similar to creating a component. But in this case, we use the @Directive decorator. For our example, we’ll be creating a directive called “my-error-directive”, which will highlight in red the background of an element to indicate an error.

For our example, we’ll be using the Angular 2 quickstart package. We just have to clone the repository, then run npm install and npm start. It will provide us a boilerplate app that we can use to experiment. We’ll build our examples on top of that boilerplate.

Let’s start by creating a file called app.myerrordirective.ts on the src/app folder and adding the following code to it:

import {Directive, ElementRef} from '@angular/core';

@Directive({

selector:'[my-error]'

})

export class MyErrorDirective{

constructor(elr:ElementRef){

elr.nativeElement.style.background='red';

}

}

After importing the Directive from @angular/core we can then use it. First, we need a selector, which gives a name to the directive. In this case, we call it my-error.

Best practice dictates that we always use a prefix when naming our Angular directives. This way, we’re sure to avoid conflicts with any standard HTML attributes. We also shouldn’t use the ng prefix. That one’s used by Angular, and we don’t want to confuse our custom created Angular directives with Angular predefined ones. In this example, our prefix is my-.

We then created a class, MyErrorDirective. To access any element of our DOM, we need to use ElementRef. Since it also belongs to the @angular/core package, it’s a simple matter of importing it together with the Directive and using it.

We then added the code to actually highlight the constructor of our class.

To be able to use this newly created directive, we need to add it to the declarations on the app.module.ts file:

import { NgModule } from '@angular/core';

import { BrowserModule } from '@angular/platform-browser';

import { MyErrorDirective } from './app.myerrordirective';

import { AppComponent } from './app.component';

@NgModule({

imports: [ BrowserModule ],

declarations: [ AppComponent, MyErrorDirective ],

bootstrap: [ AppComponent ]

})

export class AppModule { }

Finally, we want to make use of the directive we just created. To do that, let’s navigate to the app.component.ts file and add the following:

import { Component } from '@angular/core';

@Component({

selector: 'my-app',

template: `<h1 my-error>Hello {{name}}</h1>`,

})

export class AppComponent { name = 'Angular'; }

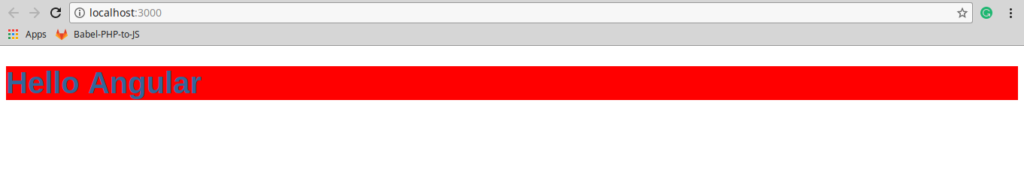

The final result looks similar to this:

Creating a structural directive

In the previous section, we saw how to create an attribute directive using Angular. The approach for creating a structural behavior is exactly the same. We create a new file with the code for our directive, then we add it to the declarations, and finally, we use it in our component.

For our structural directive, we’ll implement a copy of the ngIf directive. This way, we’ll not only be implementing a directive, but also taking a look at how Angular directives handle things behind the scenes.

Let’s start with our app.mycustomifdirective.ts file:

import { Directive, Input, TemplateRef, ViewContainerRef } from '@angular/core';

@Directive({

selector: '[myCustomIf]'

})

export class MyCustomIfDirective {

constructor(

private templateRef: TemplateRef<any>,

private viewContainer: ViewContainerRef) { }

@Input() set myCustomIf(condition: boolean) {

if (condition) {

this.viewContainer.createEmbeddedView(this.templateRef);

} else {

this.viewContainer.clear();

}

}

}

As we can see, we’re using a couple of different imports for this one, mainly: Input, TemplateRef and ViewContainerRef. The Input decorator is used to pass data to the component. The TemplateRef one is used to instantiate embedded views. An embedded view represents a part of a layout to be rendered, and it’s linked to a template. Finally, the ViewContainerRef is a container where one or more Views can be attached. Together, these components work as follows:

Directives get access to the view container by injecting a

ViewContainerRef. Embedded views are created and attached to a view container by calling theViewContainerRef’screateEmbeddedViewmethod and passing in the template. We want to use the template our directive is attached to so we pass in the injectedTemplateRef. — from Rangle.io’s Angular 2 Training

Next, we add it to our declarators:

import { NgModule } from '@angular/core';

import { BrowserModule } from '@angular/platform-browser';

import { MyErrorDirective } from './app.myerrordirective';

import { MyCustomIfDirective } from './app.mycustomifdirective';

import { AppComponent } from './app.component';

@NgModule({

imports: [ BrowserModule ],

declarations: [ AppComponent, MyErrorDirective, MyCustomIfDirective ],

bootstrap: [ AppComponent ]

})

export class AppModule { }

And we use it in our component:

import { Component } from '@angular/core';

@Component({

selector: 'my-app',

template: `<h1 my-error>Hello {{name}}</h1>

<h2 *myCustomIf="condition">Hello {{name}}</h2>

<button (click)="condition = !condition">Click</button>`,

})

export class AppComponent {

name = 'Angular';

condition = false;

}

The kind of approach provided by structural directives can be very useful, such as when we have to show different information for different users based on their permissions. For example, a site administrator should be able to see and edit everything, while a regular user shouldn’t. If we loaded private information into the DOM using an attribute directive, the regular user and all users for that matter would have access to it.

Angular Directives: Attribute vs Structural

We’ve looked at attribute and structural directives. But when should we use one or the other?

The answer might be confusing and we can end up using the wrong one just because it solves our problems. But there’s a simple rule that can help us choose the right one. Basically, if the element that has the directive will still be useful in the DOM when the DOM is not visible, then we should definitely keep it. In this case, we use an attribute directive like hidden. But if the element has no use, then we should remove it. However, we have to be careful to avoid some common pitfalls. We have to avoid the pitfall of always hiding elements just because it’s easier. This will make the DOM much more complex and probably have an impact on overall performance. The pitfall of always removing and recreating elements should also be avoided. It’s definitely cleaner, but comes at the expense of performance.

All in all, each case should be carefully analyzed, because the ideal solution is always the one that has the least overall impact on your application structure, behavior and performance. That solution might be either attribute directives, structural directives or, in the most common scenario, a compromise between both of them.

Conclusion

In this article, we took a look at Angular directives, the core of Angular applications. We looked at the different types of directives and saw how to create custom ones that suit our needs.

I hope that this article was able to get you up and running with Angular directives. If you have any questions, feel free to use the comment section below.