Power Up Your Team by Using Scrum Properly

The following is a short extract from our recent book, Scrum: Novice to Ninja, available for free to SitePoint Premium members. Print copies are sold in stores worldwide, or you can order them here. We hope you enjoy this extract and find it useful.

What Is Scrum?

If you picked up this book to learn about applying scrum to your web or mobile development team, you may already be familiar with the terms scrum and agile. Perhaps you received this book from your company, or maybe you’ve been tasked with implementing an agile process in your own organization. Whatever the reason, it’s always useful to start with a clear, shared definition of the relevant terms.

Scrum is one of several techniques for managing product development organizations, lumped under the broad category of agile software development. Agile approaches are designed to support iterative, flexible, and sustainable methods for running a product engineering organization.

Among the various agile techniques, scrum is particularly well suited to the types of organizations that develop products such as websites and mobile software. The focus on developing cohesive, modular, measurable features that can be estimated relatively, tracked easily, and that may need to adapt quickly to changing market conditions makes scrum particularly appropriate for these types of projects.

Scrum encourages teams to work in a focused way for a limited period of time on a clearly defined set of features, understanding that the next set of features they may be asked to work on could be unpredictable because of changes in the marketplace, feedback from customers, or any number of factors. Scrum allows teams to develop an improved ability to estimate how much effort it will take to produce a new feature in a relative way, based on the work involved in features they’ve developed before. And scrum creates the opportunity for a team to reflect on the process and improve it regularly, bringing everybody’s feedback into play.

Warning: Don’t Confuse Merely Applying Scrum Terms with Actually Using Scrum

A familiar anti-pattern in non-agile organizations looking to mask their process problems is using the terminology of scrum as a labeling system on top of their waterfall techniques and tools. That can create confusion, and even negative associations among people who have seen these terms used incorrectly, and who mistakenly believe they’ve seen scrum in action.

As we go through this book, you’re going to find out more about how scrum functions. You’re going to be introduced to all of the aspects of scrum, including its rituals, its artifacts, and the roles that it creates for the people in an organization. We’re going to introduce you to a team of people working in a scrum environment, and show you how they adopted scrum in the first place, and how they adapted to it.

Before we get there, it’s worthwhile taking a moment to position scrum in its historical context. After all, scrum isn’t the only way to organize product development. Scrum came into existence right around the time that web development emerged on the engineering landscape, and it flourished as mobile technology became part of our daily lives. If you consider how scrum works, where it came from, and how we apply it, I think you’ll see that there might be a reason for that.

Note: Scrum’s Odd Vocabulary

The vocabulary of scrum is distinctive, and may sound odd. That’s intentional. Scrum uses terms such as ritual, artifact, and story to make it clear that these concepts are different from related ideas that may be encountered in other project management approaches.

A Brief History of Scrum

The original concept for scrum came out of Japan, introduced in 1986 as part of The New Product Development Game by Hirotaka Takeuchi and Ikujiro Nonaka. They applied the concept of a scrum, taken from the team game rugby, to describe cross-functional team organization based around moving forward in a layered approach.

Their concepts were codified as the Scrum Methodology at a joint presentation in 1995 by Ken Schwaber and Jeff Sutherland, based on their personal experiences applying the concepts in their own organizations. This work inspired the 2001 book, Agile Software Development with Scrum, written by Schwaber and Mike Beedle.

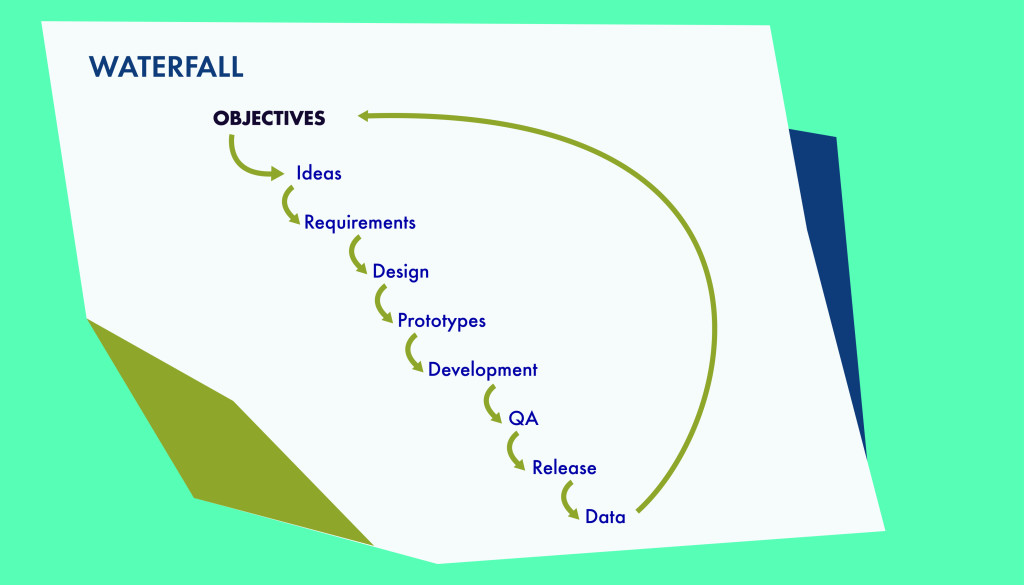

At the time, the most prevalent approach for software development was called the waterfall model. Under the waterfall model, product development happens in stages, leading sequentially from requirements through design, implementation, and release. Until the 1990s, most software development was targeted at packaged software delivery for desktop computers. Such products had long development and release cycles. While waterfall is well-suited to products that have a long development trajectory, it doesn’t adapt well to situations where the product needs to change constantly in response to changing conditions.

In the mid-to-late 1990s, new publishing models emerged involving electronic media and the Internet. To support these, software development organizations had to incorporate more flexibility to adapt to changing browsers, tight media deadlines, and a variety of platforms with different requirements. Soon after that, the development of large monolithic software applications that lived on desktop computers gave way to smaller, more nimble apps that were delivered through mobile devices. A different approach was needed for developing these.

It isn’t a coincidence that agile approaches became codified, and quickly became popular, just as the marketplace was shifting from desktop software to web and mobile software.

Comparing Scrum and Waterfall

The slow cycle of waterfall development may still be appropriate in a world of hardware development, or even in gaming. These industries rely on long, stable markets, where many of the decisions are either repetitive, constrained by external resources, or need to be made far in advance because of the massive scale and expense of development.

Web and mobile technology moves too fast for a waterfall approach. By the time you’re done developing a solution to one problem and gathering feedback from users, the technology has already moved on, and you may have a very small window of opportunity to capitalize on your solution.

In a waterfall approach, the ideas for what needs to be developed may come from customers, from the executives, from market research, or from the imagination of people making the decisions and setting the budgets. Those ideas are passed on to product managers, who create a long product roadmap. They establish and collect requirements, write out classic product requirement documents, and then pass those requirements on to designers to create prototypes as wireframes and mockups. Those prototypes are passed on to an engineering team that implements those ideas, and produces a product that can finally be released to the marketplace. Until that product is released and put in the hands of customers, no feedback into the process is generated.

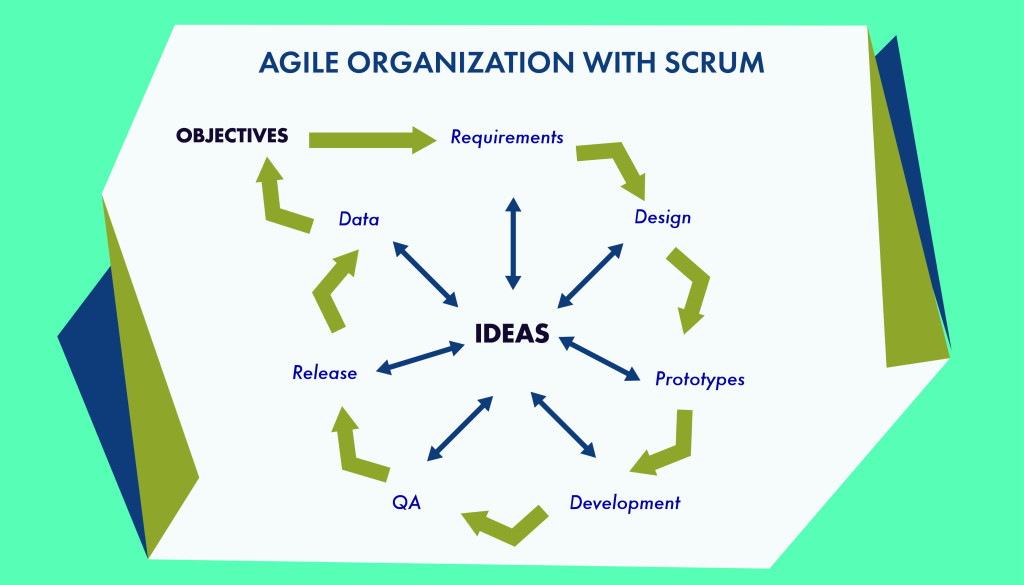

In an agile organization, guiding objectives and key performance indicators guide the process, but the team manages itself to meet those objectives. A product owner maintains the overall vision, and works with the scrum master to make sure that everyone on the team is clear about the objectives and how they’ll be measured. The input of the designers and the engineers is included at every stage in this process. Features are conceived and formulated into stories when the team is ready to work on them. No idea gets locked into a static product timeline.

The value to a company of hiring its own team of designers and engineers is that these people can bring their design thinking and their current technical knowledge to the table for the benefit of the organization’s own objectives. Designers should be evaluating the user experience and figuring out the best solutions to real customers’ problems, not decorating bad ideas to make them functional.

Getting engineers involved in ideation allows them to pull in the latest technology as early as possible, since they’re in the best position to know what’s technically feasible. The sooner the designers and engineers are brought into the planning process, the more agile development will be.

Scrum allows the full resources of the team to be applied when and where they can do the most good, and to work together in a sustainable and productive way. Instead of waiting until the entire cycle has completed before any data can be fed back into the system, ideas are generated at every stage, and encouraged to bubble to the surface at the end of each sprint. Total participation of the team in every stage of the process allows these ideas to feed into the objectives, and support the vision of the organization.

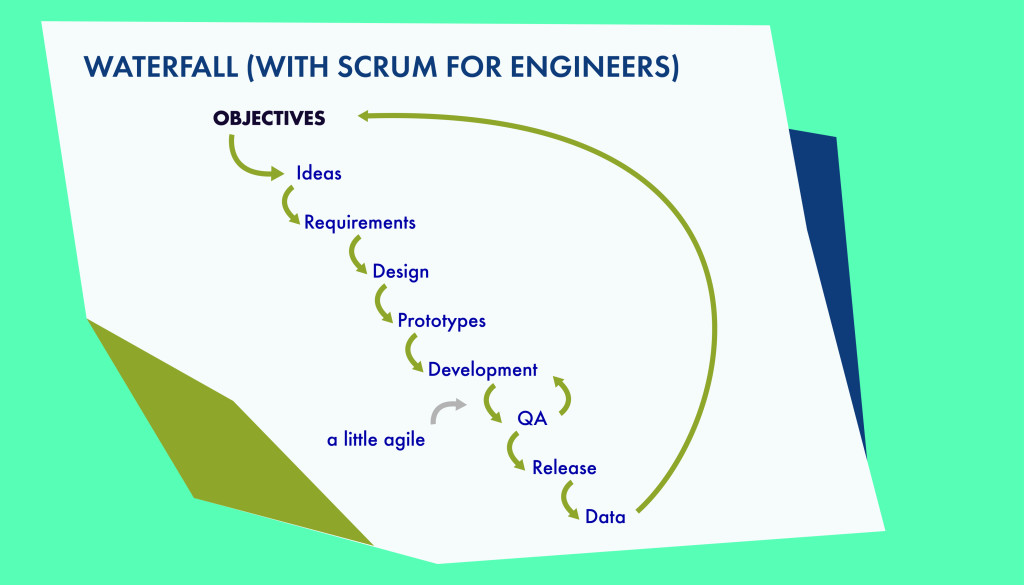

Warning: Mixing Scrum With Waterfall

While some organizations may claim to follow scrum, many of them actually follow a modified waterfall approach, using scrum techniques only for development. The rest of the organization structures itself around long-lived product timelines with static objectives. While that may be an improvement over pure waterfall, in that it allows the engineers to iterate and improve their process, it doesn’t take full advantage of the potential of scrum. Isolating scrum inside the development loop without inviting the learnings of the team into the planning and market testing process is a waste of resources, and a wasted opportunity.

Mixing a little scrum into an otherwise waterfall organization is usually not a good idea, since it can draw attention to the fundamental conflicts between the different approaches, and foster friction.

Reasons to Choose Scrum for Web and Mobile

We’ve covered how scrum works, and why it’s a productive way to structure web and mobile product development. At this point, it’s worth taking a moment to recap some of the highlights of how scrum applies in particular to web and mobile product development.

Fundamentally, scrum offers a team-based approach to project work that allows a product development process to benefit from iterative self-reflection, helps a team learn how to estimate their own ability to address unfamiliar tasks, exposes metrics about team effectiveness, encourages dialogue about feature implementation instead of static specifications, and supports rapid response to changing market conditions in a sustainable manner.

All of those advantages can make a real difference when doing web and mobile development. Most work in web or mobile development tends to be very time sensitive, and needs to respond quickly to changes in the marketplace. Whether that means new browsers, new technologies, or new messaging that needs to be communicated immediately, web and mobile teams have to be able to respond quickly.

Scrum provides a framework that allows developers to work toward a vision, and the opportunity to shift direction as the environment changes without feeling torn away from their focus.

When following best development practices, the type of work that’s involved in building and enhancing a web or mobile project tends to break down into discrete pieces that can be worked on independently, with a core of infrastructure stories that support a broad range of independent feature stories. This makes it easier for one part of a web or mobile project to be developed in isolation, and leverage the shared resources of other parts of the same project.

Scrum encourages teams to spell out the work on a new feature so that it can be developed in parallel, without relying on other undeveloped features. By using stories, and making sure each story is properly formatted and estimated, the team sets itself up for a consistent and productive development experience.

Note: Some Scrum Terms Defined

When scrum uses a word, it means just what scrum chooses for it to mean. But unlike Humpty Dumpty in Through the Looking Glass, scrum relies on familiar and easily understood definitions. Learning the language is one of the first steps in acquiring a new skill, and consistent use of language is fundamental to teams trying to work together. The terms below are only some of the ones that will be defined in much more detail later in the book, but a brief glance through these concepts may help as you read on.

- Agile

-

a set of software development practices designed to help engineers work together and adapt to changes quickly and easily.

- Artifact

-

a physical or virtual tool used by a scrum team to facilitate the scrum process

- Blocker

-

anything keeping an engineer from moving forward on a task in progress

- Customer

-

whoever has engaged the team to create a product

- Engineer/Developer

-

a person responsible for creating and maintaining the technology that goes into a product

- Engineering Organization

-

the part of a company where engineers are employed to create and maintain products

- Product

-

what the engineering organization is building or maintaining for a customer

- Product backlog

-

a constantly evolving list of potential features or changes for a product

- Product owner

-

a person who helps define the product for the team, and whose job may be on the line if the customer isn’t satisfied

- Retrospective

-

a regular opportunity for the team to reflect on how they are doing, and what they could do better

- Ritual

-

a group of people coming together as part of the scrum process for a fixed time, with a specified agenda, to achieve a clearly defined outcome

- Scrum Master

-

a person responsible for maintaining the artifacts and overseeing the rituals of scrum

- Sprint

-

a fixed number of days during which the team can work together to produce an agreed upon set of changes to the product

- Sprint backlog

-

a finite and well-defined set of stories the team has agreed they can reasonably complete in the current sprint

- Story

-

a clear and consistent way of chunking, phrasing, and discussing work the team may need to do on the product

- User

-

a person who will be making use of the product

Scrum is also flexible enough to support working styles for product owners who prefer to break down stories that can be completed in one week, two weeks, three weeks, four weeks or longer. While most web and mobile development teams tend to split the work into one- or two-week segments—known in scrum terminology as sprints—whatever the team agrees on should work. As long as the team is keeping track of how they work together, and they’re given the opportunity to reflect on a regular basis about their schedules, scrum can adapt to work on projects ranging from the simplest to the most complex.

Time Sensitivity

Scrum provides opportunities in every sprint to integrate the ideas of designers, engineers, executives, customers, product managers, and customers through real customer data. Because of the cyclical nature of scrum, and the iterative approach that encourages learning as you go, scrum allows mobile and web projects to adapt to changing technologies and changing market expectations quickly.

Modular Development

Scrum supports the ability to develop a project in modules. Because scrum is based on thinking in terms of slices of functionality, it’s perfectly suited for making independent, interoperable features that can be developed atomically and work together harmoniously.

For example, a new section for a website may inherit styling from a shared style guide and CSS structure, and may inherit its functionality from a shared template. The work to build out that section relies on those other components remaining static long enough to complete the work. Scrum provides the stability to support that, without limiting the development of the rest of the site.

At the same time, updating the infrastructure of a product to support a new feature may happen at any time in the process, so a team has to consider up front how to make those changes safely, without breaking the work being done on other features.

As another example, sometimes an API that every feature of the site relies on needs to be changed. Scrum encourages the team to manage the code in a modular, testable way, so that changes can be inherited by other feature stories that might be in progress without undue breakage.

Flexible Scheduling

Companies serving customers in the web and mobile space need to be able to respond quickly to changes. However, engineers need to be confident that what they’re working on isn’t going to change before they can get the feature developed. It can be difficult to balance those two objectives.

Scrum provides windows of opportunity that are long enough to allow a web or mobile feature to be fully developed, while still allowing a product to change directions at the end of each sprint, based on data from the marketplace.

Reflection and Improvement

A scrum team isn’t only looking to improve the product: they’re also looking to improve their own process. Scrum teams get better over time at estimating how much work they can do, and improving their approach to working so that they can be the most productive.

By giving the team the opportunity to look at its own process, and figure out how it works best together, scrum makes maximum use of the limited resources of any organization.

Summary

That was a quick overview of scrum, taken from a 30,000-foot perspective. We had a brief introduction to how scrum works, and why it can be effective for certain types of product development. We contrasted scrum with the more traditional waterfall approach for software development, and discussed why it emerged when it did. We also noted how well suited scrum is for web and mobile development projects.

But scrum isn’t just an abstract concept and a bunch of unfamiliar buzzwords. Scrum is a practical and flexible approach to product development that relies on the active and engaged participation of real people. So in the next chapter, we’re going to meet a few of the typical people who might work in a web or mobile development organization. We’ll talk to them about some of their frustrations, find out what they hope to get out of scrum, and ask them about their concerns when they consider scrum.

As we go through this book, keep these people in mind. We’ll be meeting them again, and following them through their process as they learn and start to apply scrum to their work.

Enjoyed this chapter? Download the whole book (and our entire book library!) by joining SitePoint Premium