A Guide to HTML & CSS Forms (No Hacks!)

Historically, HTML forms have been quite tricky — firstly, because at least a little bit of JavaScript was required, and secondly, because no amount of CSS could ever make them behave.

However, this isn’t necessarily true in the case of the modern web, so let’s learn how to mark up forms using only HTML and CSS.

Form-ing the basic structure

Start off with the <form> element.

Nothing fancy here. Just covering the basic structure.

<form>

...

</form>

If you’re submitting the form data naturally (that is, without JavaScript), you’ll need to include the action attribute, where the value is the URL you’ll be sending the form data to. The method should be GET or POST depending on what you’re trying to achieve (don’t send sensitive data with GET).

Additionally, there’s also the lesser-used enctype attribute which defines the encoding type of the data being sent. Also, the target attribute, although not necessarily an attribute unique to forms, can be used to show the output in a new tab.

JavaScript-based forms don’t necessarily need these attributes.

<form method="POST" action="/subscribe" enctype="application/x-www-form-urlencoded" target="_blank">

...

</form>

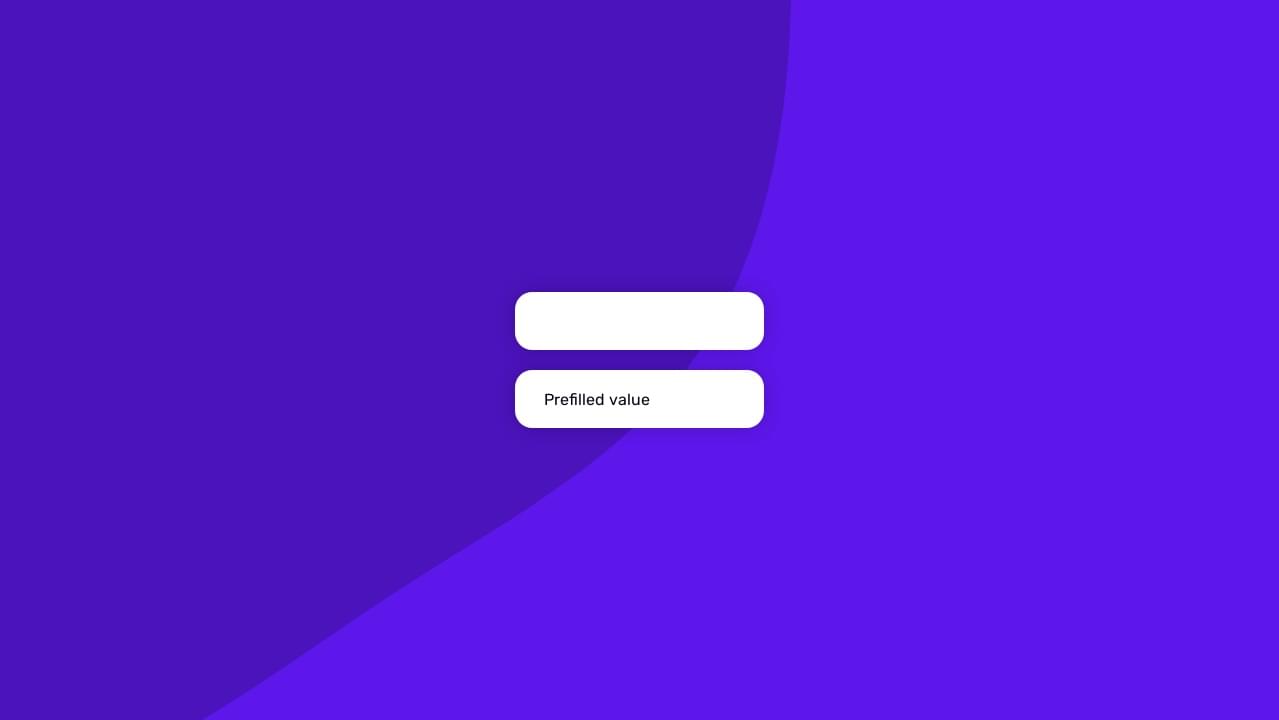

Forms are made up of inputs, which expect data values.

<form>

<input type="text"><!-- text input -->

<input type="text" value="Prefilled value">

</form>

See the Pen

Form 1 by SitePoint (@SitePoint)

on CodePen.

Including Labels for Better Usability & Accessibility

Every input needs a label.

A label is a text descriptor that describes what an input is for. There are three ways to declare a label, but one of them is superior to the other two. Let’s dive into these now.

Adjacent labels

Adjacent labels require the most code because we need to explicitly declare which input the label describes. To most, this is counterintuitive because we can instead wrap inputs inside labels to achieve the same effect with less code.

That being said, the adjacent method may be necessary in extenuating circumstances, so here’s what that would look like:

<label for="firstName">First name</label>

<input id="firstName">

As you can see from the example above, the for attribute of the <label> must match the id attribute of the input, and what this does is explain to input devices which text descriptor belongs to which input. The input device will then relay this to users (screen readers, for example, will dictate it via speech).

ARIA labels

While semantic HTML is better, ARIA (Accessible Rich Internet Applications) labels can compensate in their absence. In this case, here’s what a label might look like in the absence of an actual HTML <label>:

<input aria-label="First name">

Unfortunately, the downside of this approach is the lack of a visual label. However, this might be fine with some markups (for example, a single-input form with a heading and placeholder):

<h1>Subscribe</h1>

<form>

<input aria-label="Email address" placeholder="bruce@wayneenterpris.es">

</form>

(I’ll explain what placeholders are for in a moment.)

Wrapping labels

Wrapping inputs within labels is the cleanest approach. Also, thanks to CSS’s :focus-within, we can even style labels while their child inputs receive focus, but we’ll discuss that later.

<label>

First name<input>

</label>

Placeholders vs labels

A brief comparison:

- Labels state what the input expects

- Placeholders show examples of said expectations

Placeholders aren’t designed to be the alternative to labels, although as we saw in the ARIA example above, they can add back some of the context that’s lost in the absence of visual labels.

Ideally, though, we should use both:

<label>

First name<input placeholder="Bruce">

</label>

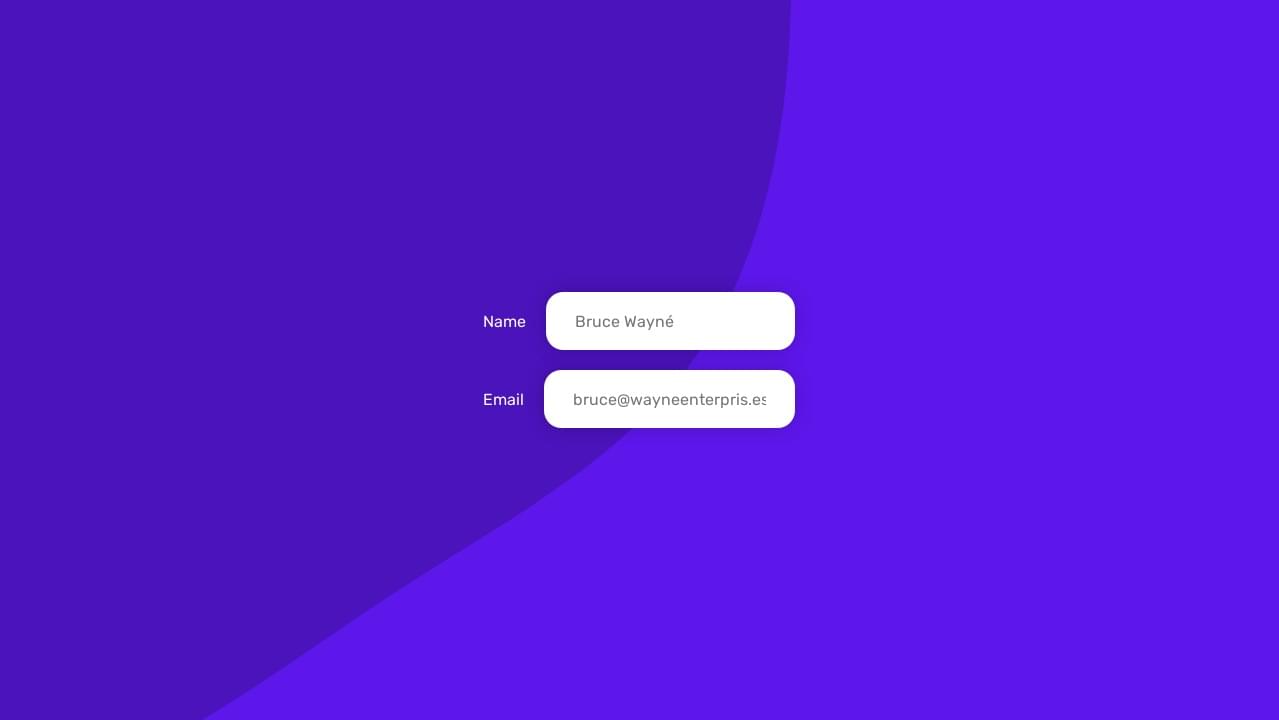

See the Pen

Form 2 by SitePoint (@SitePoint)

on CodePen.

Choosing Input Types

Placeholders only apply to text-based inputs, but there are actually a whole range of different input types, which include:

<input type="button">

<input type="checkbox">

<input type="color">

<input type="date">

<input type="datetime-local">

<input type="email">

<input type="file">

<input type="hidden"> <!-- explained later -->

<input type="image">

<input type="month">

<input type="number">

<input type="password">

<input type="radio">

<input type="range">

<input type="reset">

<input type="search">

<input type="submit"> <!-- submits a form -->

<input type="tel">

<input type="text"> <!-- the default -->

<input type="time">

<input type="url">

<input type="week">

Semantic input types are useful during form validation, especially when relying on native validation, which we’ll take a look at shortly. First, let’s learn how to style these inputs.

Styling inputs

Arguably the most infuriating aspect of coding forms is overriding the browser’s default styling. Thankfully, today, appearance: none; has 96.06% browser support according to caniuse.com.

After resetting the web browser’s default styling with the following CSS code, we can then style inputs however we want, and this even includes both the radio and checkbox input types:

input {

-webkit-appearance: none;

-moz-appearance: none;

appearance: none;

...

}

However, some of these inputs might come with quirks that are difficult or even impossible to overcome (depending on the web browser). For this reason, many developers tend to fall back to the default type="text" attribute=value if they find these quirks undesirable (for example, the “caret” on input type="number").

However, there is a silver lining …

Specifying an inputmode

With 82.3% web browser support according to caniuse.com, the new inputmode attribute specifies which keyboard layout will be revealed on handheld devices irrespective of the input type being used.

Better than nothing, right?

<input type="text" inputmode="none"> <!-- no keyboard 👀 -->

<input type="text" inputmode="text"> <!-- default keyboard -->

<input type="text" inputmode="decimal">

<input type="text" inputmode="numeric">

<input type="text" inputmode="tel">

<input type="text" inputmode="search">

<input type="text" inputmode="email">

<input type="text" inputmode="url">

Validating User Input

Should you choose native-HTML validation over a JavaScript solution, remember that inputmode achieves nothing in this regard. inputmode="email" won’t validate an email address, whereas input type="email" will. That’s the difference.

Putting this aside, let’s discuss what does trigger validation:

<input required> <!-- value is required -->

<form required> <!-- all values are required -->

<!-- alternative input types -->

<input type="email"> <!-- blank or a valid email address -->

<input type="email" required> <!-- must be a valid address -->

<!-- text-based inputs -->

<input minlength="8"> <!-- blank or min 8 characters -->

<input maxlength="32"> <!-- blank or max 32 characters -->

<input maxlength="32" required> <!-- max 32 characters -->

<!-- numeric-based inputs -->

<input type="date" min="yyyy-mm-dd"> <!-- min date -->

<input type="number" max="66" required> <!-- max number -->

Creating custom rules

Custom rules require knowledge of JavaScript regular expressions, as used by the RegExp object (but, without wrapping slashes or quotes). Here’s an example that enforces lowercase characters (a–z) and minlength/maxlength in one rule:

<input pattern="[a-z]{8,12}">

Note: front-end validation (native-HTML or otherwise) should never, ever be used as a substitute for server-side validation!

Styling valid/invalid states

Just for extra clarity, this is how we’d style validity:

input:valid {

border-left: 1.5rem solid lime;

}

input:invalid {

border-left: 1.5rem solid crimson;

}

form:invalid {

/* this also works, technically! */

}

Houston, we have a problem!

Inputs attempt to validate their values (or lack thereof) immediately, so the following code (which only shows the valid/invalid states while the input holds a value) might be better:

input:not(:placeholder-shown):valid {

border-left: 1.5rem solid lime;

}

This shows the valid/invalid styling but only when the placeholder isn’t shown (because the user typed something).

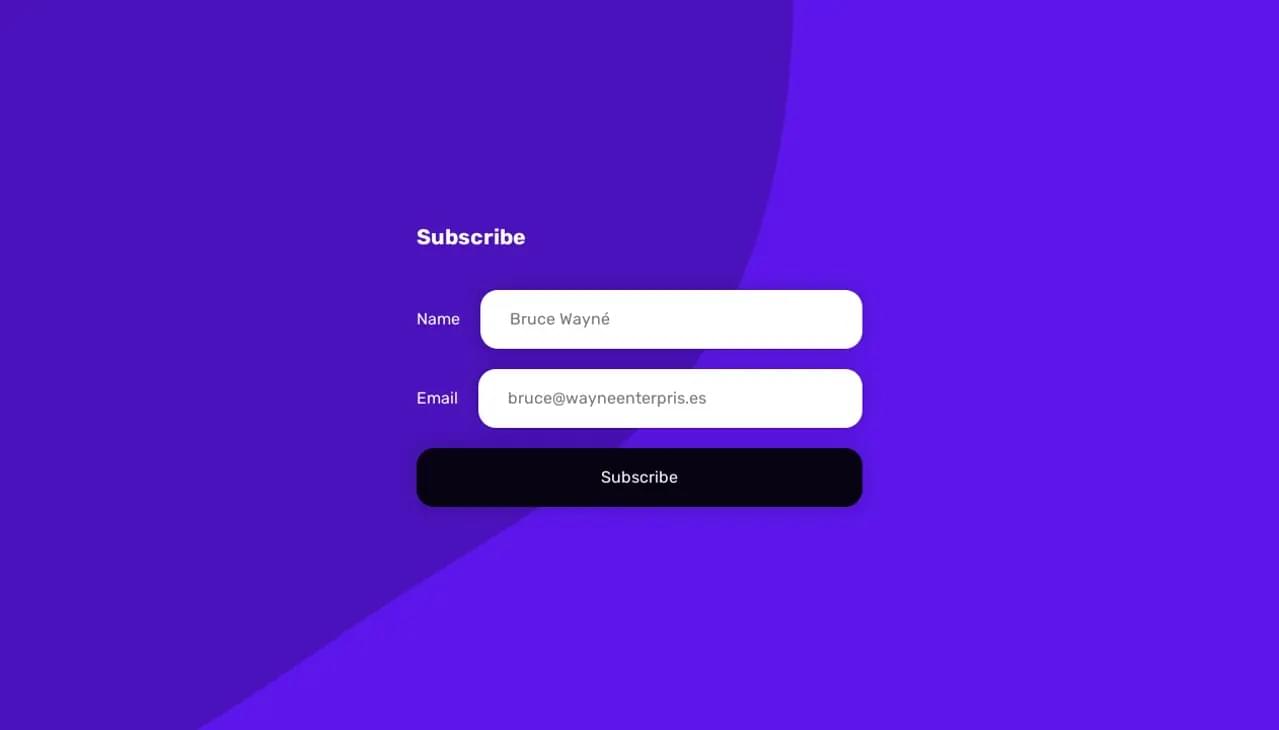

See the Pen

Form 3 by SitePoint (@SitePoint)

on CodePen.

Other Basic Things

Sending form data

Sending form data to the server usually requires that inputs have the name attribute. This also applies to hidden inputs:

<input type="email" name="email">

<input type="hidden" name="email" value="{{ user.email }}">

Accepting long-form input

Essentially, <textarea></textarea> is the same thing as <input type="text">, except for the fact that textareas have multiline support. Yes, <input type="textarea"> would certainly be more intuitive, but alas <textarea></textarea> is the correct way to accept long-form input from users. Plus, it accepts most (if not all) of the attributes that inputs do.

Grouping inputs for better accessibility

Although shorter forms offer a much better user experience, sometimes longer ones are unavoidable. In such scenario, the <fieldset> element can be used to contain related inputs, with a child <legend> being used as a title/heading for the <fieldset>:

<fieldset>

<legend>Name</legend>

<input type="text" name="title">

<input type="text" name="firstName">

<input type="text" name="lastName">

</fieldset>

<fieldset>

<legend>Contact details</legend>

<input type="email" name="email">

<input type="tel" name="homePhone">

<input type="tel" name="mobilePhone">

</fieldset>

Nice-to-know things

Disabling inputs

Adding the disabled attribute can render an input (or any focusable element) defunct, although this would typically be applied/unapplied via JavaScript. Here’s how it works, though:

<form disabled>...</form>

<fieldset disabled>...</fieldset>

<input type="submit" disabled>

And the accompanying CSS, if needed:

:enabled {

opacity: 1;

}

:disabled {

opacity: 0.5;

}

However, if all that you want to do is add an extra visual cue hinting that the user’s input isn’t valid, you would most likely want to use the general sibling combinator (~). The following code basically means “the submit button that follows any element with invalid input”. This doesn’t alter any functionality, but when we’re leveraging native-HTML form validation (which handles disabling/enabling of submit-ability automatically), this is fine:

:invalid ~ input[type=submit] {

opacity: 0.5;

}

Disabling an input, but sending the data anyway

A mix of <input disabled> and <input type="hidden">, the following example will ensure that the value cannot be changed. The difference is that, unlike disabled, readonly values are sent as form data; and unlike hidden, readonly is visible:

<input readonly value="Prefilled value">

Altering increments

Numeric-based inputs have a “spin button” to adjust the numerical value, and they also accept a step attribute which determines an alternative incremental value of each adjustment:

<input type="number" step="0.1" max="1">

Styling forms, labels, and fieldsets on focus

We can use focus-within: to style any parent of an input currently receiving focus. Most likely this element will be the input’s <form>, <label>, or <fieldset> container:

form:focus-within,

fieldset:focus-within,

label:focus-within {

...

}

Sending multiple values with one input

multiple is valid for the file and email input types:

<input multiple type="file"> <!-- multiple files -->

<input multiple type="email"> <!-- comma-separated emails -->

Writing shorthand form code

If a form consists only of a singular <button>, <input type="image">, or <input type="submit">, there’s a shorthand method of marking up HTML forms. Here’s an example:

<input type="image" formaction formmethod formenctype formtarget>

As opposed to this:

<form action method enctype target>

<input type="image">

</form>

Did I Miss Anything?

HTML is so much more intuitive than it was, say, 10 years ago. It’s constantly evolving and no doubt there will be more to add on the subject of HTML/CSS forms in due time. One example that springs to mind is the datalist element, which at the moment can be quite buggy (especially in Firefox). But that aside, did I miss anything?

I’ll end by noting that there are some aspects of HTML forms that I didn’t discuss because their use isn’t recommended, including:

- Autofocus (bad for accessibility)

- Autocomplete (not using autocomplete should be the user’s choice, not the default)

- Accesskey (bad support and accessibility)

- Novalidate (this is useless without JavaScript)

FAQs About HTML Forms

An HTML form is a crucial element used to collect and gather user input on a web page. It allows users to enter data, make selections, and submit information to a server for processing.

To create a basic HTML form, you use the <form> element and include various input elements like text fields, checkboxes, radio buttons, and buttons within it. The form tag has attributes like action and method that specify where the data should be sent and how it should be processed.

Common input types include text fields (<input type="text">), checkboxes (<input type="checkbox">), radio buttons (<input type="radio">), dropdown lists (<select>), and buttons (<button>).

User input is handled using server-side scripts or client-side scripts (like JavaScript). The form’s action attribute specifies the URL where the data is sent, and the method attribute defines the HTTP method (GET or POST) used for submission.

The GET method appends data to the URL, visible in the address bar, and is suitable for less sensitive data. The POST method sends data in the request body, keeping it hidden from users, making it more secure for sensitive information.

Form data can be validated using HTML attributes like required or by using JavaScript for more complex validation. JavaScript allows you to perform real-time validation, ensuring that the data entered meets specific criteria before submission.

Yes, you can style HTML forms using CSS. You can modify the appearance of form elements, adjust layouts, and apply styles to improve the overall visual appeal and user experience.

Yes, you can enable file uploads with the <input type="file"> element. This allows users to select and submit files through the form. The enctype attribute of the form should be set to “multipart/form-data” for file uploads.