Understanding the Core Concepts of User Research

The following is a short extract from our new book, Researching UX: User Research, written by James Lang and Emma Howell. It’s the ultimate guide to user research, a key part of effective UX design. SitePoint Premium members get access with their membership, or you can buy a copy in stores worldwide.

This next section is going to get a bit theoretical. Don’t worry: we’ll show you how to apply it later in the chapter. For now, though, you need the basic building blocks of research design.

In this section, we’re going to run through 10 concepts. Some may already be familiar to you, others less so. They are:

- What is data?

- Qualitative vs. quantitative

- Discovery vs. validation

- Insight vs. evidence vs. ideas

- Validity and representativeness

- Scaling your investment

- Multi-method approaches

- In-the-moment research

- Ethics

- Research as a team sport.

What is Data?

The research process involves collecting, organising and making sense of data, so it’s a good idea to be clear what we mean by the word ‘data’. Actually, data is just another word for observations, and observations come in many forms, such as:

- Seeing someone behave in a certain way

- Or do something we’re interested in (such as click on a particular button)

- Hearing someone make a particular comment about your product

- Noting that 3,186 people have visited your Contact Us page today

But how do you know what’s useful data, and what’s just irrelevant detail? That’s what we’ll be covering in the first few chapters, where we’ll talk about how to engage the right people, and how to ask the right questions in the right way.

And how do you know what to do with data when you’ve got it? We’ll be covering that in the final two chapters about analysis and sharing your findings. In particular, we’ll be showing you how to transform raw data into usable insight, evidence and ideas.

Qualitative vs. Quantitative

When it comes to data analysis, the approaches we use can be classified as qualitative or quantitative.

Qualitative questions are concerned with impressions, explanations and feelings, and they tend to begin with why, how or what. Such as:

- “Why don't teenagers use the new skate park?"

- “How do novice cooks bake a cake?”

- “What's the first thing visitors do when they arrive on the homepage?"

Quantitative questions are concerned with numbers. For example:

- “How many people visited the skate park today?"

- “How long has the cake been in the oven for?

- "How often do you visit the website?"

Because they answer different questions, and use data in different ways, we also think of research methods as being qualitative or quantitative. Surveys and analytics are in the quantitative camp, while interviews of all sorts are qualitative. In general, you’ll be leaning on qualitative research methods more, so that will be the focus of this book.

Discovery vs. Validation

The kind of research will depend on where you are in your product or project lifecycle.

If you’re right at the beginning (in the ‘discovery’ phase), you’ll be needing to answer fundamental questions, such as:

- Who are our potential users?

- Do they have a problem we could be addressing?

- How are they currently solving that problem?

- How can we improve the way they do things?

If you’re at the validation stage, you have a solution in mind and you need to test it. This might involve:

- Choosing between several competing options

- Checking the implementation of your solution matches the design

- Checking with users that your solution actually solves the problem it’s supposed to.

What this all means is that your research methods will differ, depending on whether you’re at the discovery stage or the validation stage. If it’s the former, you’ll be wanting to conduct more in-depth, multi-method research with a larger sample, using a mix of both qualitative and quantitative methodologies. If it’s the latter, you’ll be using multiple quick rounds of research with a small sample each time.

At the risk of confusing matters, it’s worth mentioning that discovery continues to happen during validation – you're always learning about your users and how they solve their problems, so it's important to remain open to this, and adapt earlier learnings to accommodate new knowledge.

Insight, Evidence and Ideas

Research is pointless unless it’s actually used. In some cases, the purpose of research is purely to provide direction to your team; the output of this kind of project is insight. Perhaps you want to understand users’ needs in the discovery phase of your project. If so, you need insight into their current behaviour and preferences, which you’ll refer to as you design a solution.

Often, though, you need research to persuade other people, not just enlighten your immediate team. This can be where you need to make a business case, where your approach faces opposition from skeptical stakeholders, or where you need to provide justification for the choices you’ve made. When you need to persuade other people, what you need is evidence.

And sometimes, your main objective is to generate new ideas. Where that’s the case, rigorous research is still the best foundation, but you’ll want to adjust things slightly to maximise the creativity of your outputs.

Research is great at producing insight, evidence and ideas. But… methodologies that prioritise one are often weaker on the others, and vice versa. It’s much easier if you plan in advance what you’ll need to collect, and how, rather than leaving it till the end of the project. The takeout: you should think about the balance of insight, evidence and ideas you’ll need from your project, and plan accordingly.

When it comes to planning your approach, bear in mind your analysis process later on. If you give it thought at this stage, you’ll ensure you’re collecting the right data in the right way. We talk about this more in Chapter 8.

Validity

Validity is another way of saying, “Could I make trustworthy decisions based on these results?” If your research isn’t valid, you might as well not bother. And at the same time, validity is relative. What this means is that every research project is a tradeoff between being as valid as possible, and being realistic about what’s achievable within your timeframe and budget. Designing a research project often comes down to a judgement call between these two considerations.

Let’s look at an example. You want to understand how Wall Street traders use technology to inform their decision-making. If you were prioritising validity, you might aspire to recruit a sample of several hundred, and use a mix of interviewing and observation to follow their behaviour week by week over several months. That would be extremely valid, but it would also be totally unrealistic:

- Wall Street traders will be rich and busy. They’re unlikely to want to take part in your research.

- A sample of several hundred is huge. You’re unlikely to be able to manage it and process the mountain of data it would generate.

- A duration of several months is ambitious. You would struggle to keep your participants engaged over such a long period.

- Even if the above weren’t issues, the effort and cost involved would be huge.

Undaunted, you might choose to balance validity and achievability in a different way, by using a smaller number of interviews, over a shorter duration, and appealing to traders’ sense of curiosity rather than offering money as an incentive for taking part. It’s more achievable, but you’ve sacrificed some validity in the process.

Validity can take several forms. When you design a research project, ask yourself whether your approach is:

- Representative: Is your sample a cross-section of the group you’re interested in? Watch out for the way you recruit and incentivize participants as a source of bias.

- Realistic: If you’re asking people to complete a task, is it a fair reflection of what they’d do normally? For example, if you’re getting them to assess a smartphone prototype, don’t ask them to try it on a laptop.

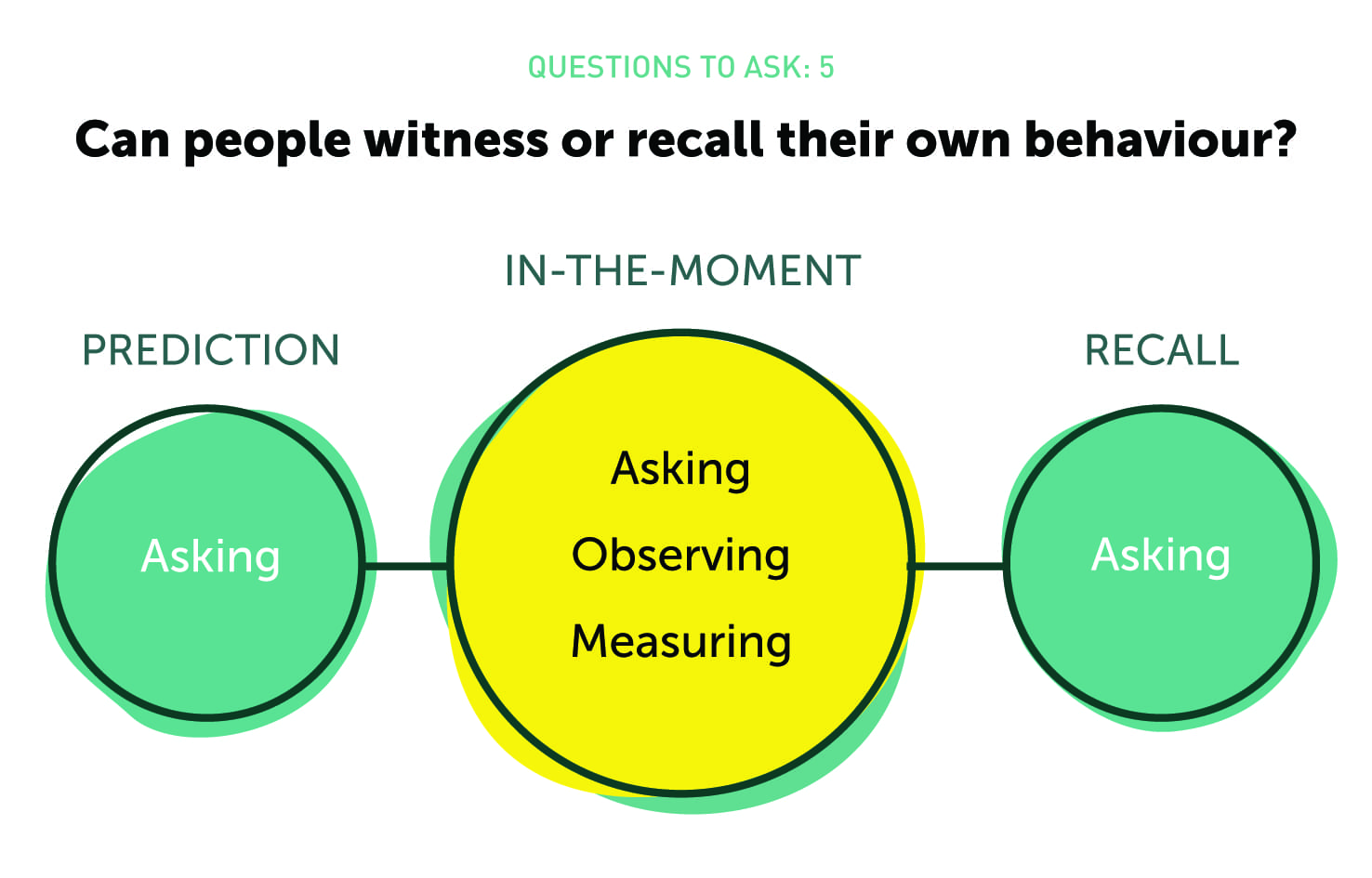

- Knowable: Sometimes people don’t know why they do things. If that’s the case, it’s not valid to ask them! For example, users may not know why they tend to prefer puzzle games to racing games, but they will probably still take a guess.

- Memorable: Small details are hard to remember. If you’re asking your participants to recall something, like how many times they’ve looked at their email in the past month, they’ll be unlikely to remember, and therefore your question isn’t valid: you need a different approach, such as one based on analytics. If you were to ask them how many times they’ve been to a funeral in the past month, you can put more trust in their answer.

- In the moment: If your question isn’t knowable or memorable, it’s still possible to tackle it ‘in the moment’. We’ll say more about this below.

Takeout: You want your research approach to be as valid as possible (ie, representative and realistic, as well as focused on questions that are knowable and memorable) within the constraints of achievability. Normally, achievability is a matter of time and budget, which leads us to…

Scaling Your Investment

Imagine you were considering changing a paragraph of text on your website. In theory, you could conduct a six-month contextual research project at vast expense, but it probably wouldn’t be worth it. The scale of investment wouldn’t be justified by the value of the change.

On the other hand, you might have been tasked with launching a game-changing new product on which the future of your organisation depended. You could go and ask two people in the street for their opinion, but that would be a crazy way to inform such a major decision. In this case, the scale of the risk and opportunity justifies a bigger research project.

So when you look at your research project, ask yourself: what’s the business value of the decisions made with this research? What’s the potential upside? What’s the potential risk? Then scale your research project accordingly. Incidentally, it’s also good practice to refer back to the business impact as a project KPI. You’ll find it much easier to justify the value of your research later on if you can show how it’s made a difference to the business numbers your colleagues care about, such as revenue, conversion rate or Net Promoter Score.

Multi-Method Approaches

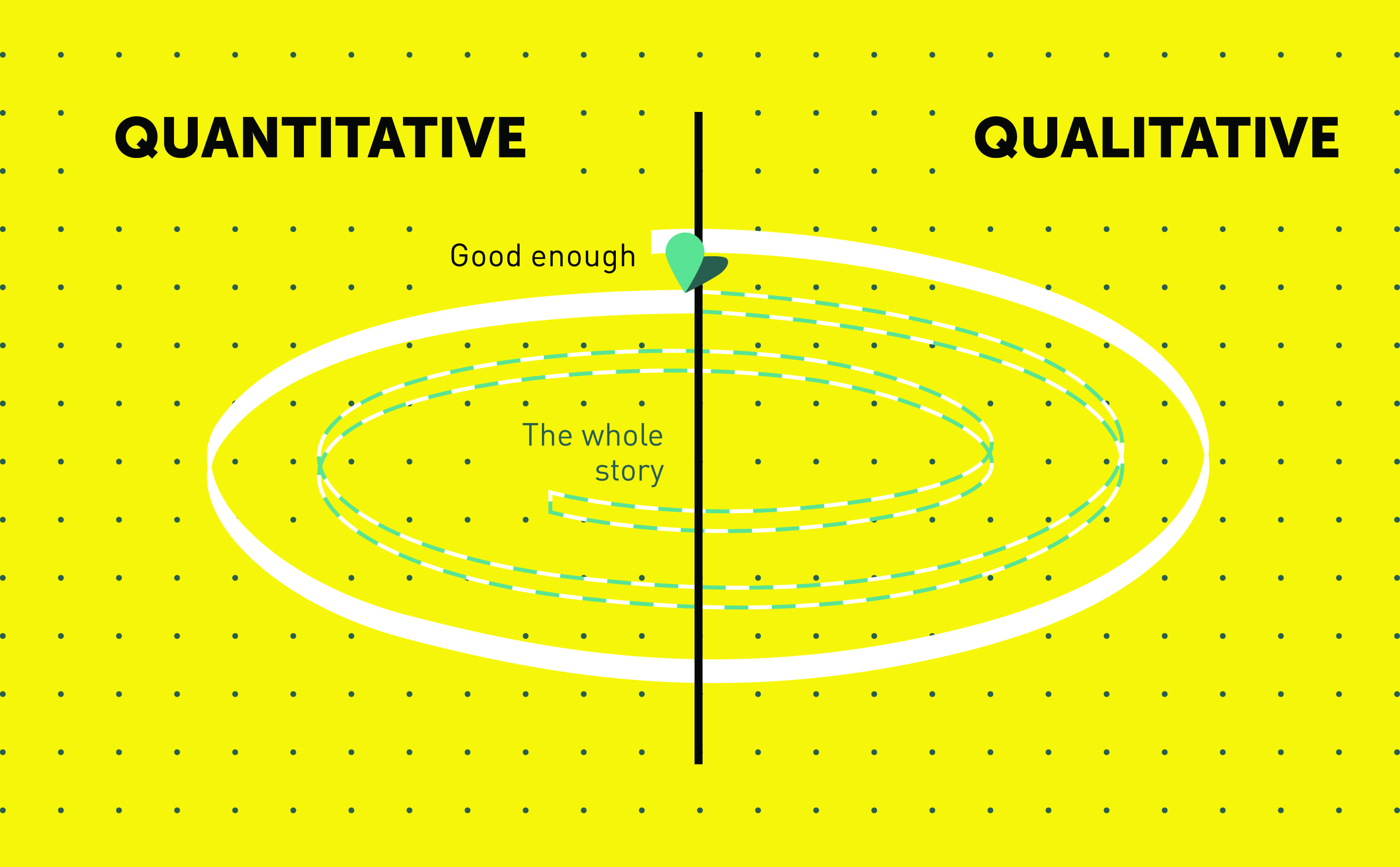

You’ll sometimes hear people talking about qualitative and quantitative methods as if they’re in opposition. Not so: they’re friends. And your research projects will always be better if you can combine both, because they counteract each other’s blind spots.

In fact, all research methods have blind spots. Although you’ve got to make a judgement call about which method to use in any given situation, you should always be aware of its limitations. But the best way to overcome these limitations is to team it up with another approach, so you can have the best of both worlds. Kristy Blazo from U1 Group describes the cycle of qualitative and quantitative stages as a spiral. Each stage builds on the last as you work round it, until you get to the point where the benefits of increased certainty are outweighed by the costs of further research.

In-The-Moment Research

Earlier, we talked about research needing to be knowable and memorable in order to be valid. Actually, that’s not always the case. If you can be present when the event you’re interested in is actually happening, you don’t need to rely on their patchy memory and interpretation to figure out what’s going on.

Imagine you’re interested in the experience of sports fans at a game. You could interview them afterwards, but it would be more insightful to be there at the event. That way, you could look at the features you’re interested in, and compare your observations to visitors’ own comments. Rather than asking them to recall the state of the toilets and the quality of the catering, you could observe yourself and interview people there and then.

In-the-moment research, then, gives a more realistic view of events than asking people afterwards. The main methods for in-the-moment research are contextual interviewing and observation, diary studies and analytics, which we’ll talk more about later in this chapter.

Takeout: If you’re interested in events and behaviour that people aren’t likely to recall accurately afterwards, you should consider in-the-moment methods, instead of approaches that involve asking them about their experiences weeks or months later, such as depth interviews and surveys.

Taking Care

Research has the power to do harm.

- By revealing participants’ identities, you could expose them to consequences in their work or community. Because of this, we hide people’s identities as default.

- Depending on what you’re researching or testing, you risk upsetting people, particularly if they’re young or vulnerable. Because of this, we take care to set up interviews in as unthreatening a way as possible, and ensure participants know they can leave at any point.

- For researchers themselves, there are risks. Visiting participants in their home requires care. Working in a state of deep empathy, sometimes on distressing subjects, can be emotionally hard to deal with, and researchers can and do get burned out as a result. Because of this, we take care with physical safety, and make sure we’re managing the emotional burden together.

Takeout: When you design your research project, consider the impact it may have on both participants and the project team. If you’re working with adults on an shoe retail website, then this isn’t something you need to worry about too much. But if you’re working with vulnerable teenagers to create an app about domestic violence, then it’s a different story.

Research as a Team Sport

Research is most effective when the whole team’s involved. Consider the difference: a project where a researcher takes a brief, goes away for a few weeks, then comes back with a report, versus a project where the whole team decides on the approach together, take turns interviewing and observing all the interviews, and analyse collectively. In the latter, you’re going to have better understanding, greater buy-in, and quicker, more effective results. Research isn’t just about generating insight, evidence or ideas: it’s also about building consensus among a multidisciplinary group who are about to tackle a problem together. The UK’s Government Digital Service calls this ‘research as a team sport’, and that’s the way we think it should be played, too.

We talk about how to work as a team in Chapter 2, and how to engage and activate the research with your wider group of stakeholders in Chapter 9.