Uncovering the Secret Coded Language of Postage Stamps

We don’t LOL as often as we used to, do we?

Five years ago, it felt like every second TXT, IM, or Facebook post would contain a lowercase LOL, if not a fully-fledged ‘ROFL‘.

A recent Facebook study claims over half of us use ‘Haha’ while ‘LOL’ usage has dropped to 1.9% of us. Poor LOL only made it into the OED in 2011 but its golden era has already passed.

But in 2016, we seem to be all about the emoji.

- The cheeky wink

;-), - The incredulous stare,

:ಠ_ಠ - The single tear

:'( - The full ‘shruggy‘

¯\_(ツ)_/¯

We’ve all learned to hack the way the text interface works to communicate messages that words alone can’t. Your mother probably does it. Maybe your kids or nephews and nieces do too.

Sure, in theory typing the words ‘I’m winking at you‘ conveys the basic meaning but it’s somehow more formal AND more creepy at the same time. A ;) is both less and more.

So, on some level, we’re all UI hackers. But we’re not the first generation to do this.

1840: When Mail was the Hot Social Platform

It’s probably hard for us to appreciate what a tech miracle the postal service was to anyone living in the mid-1800’s. While royalty and governments had run their own messaging networks for centuries, these systems had always been expensive, unreliable and difficult to comprehend. Postage rates were tied tightly to the mileage of each individual letter – like a taxi fare – except the receiver had to pay for delivery.

I imagine that email would have been far less attractive if we’d all had to pay a hefty fee for each Russian spammer or Nigerian prince spam we received. That was how all public mail services worked prior to 1840, so the idea that a working-class person could send a message anywhere in the country for a penny would have boggled minds!

Not surprisingly, the service was a roaring success, carrying huge volumes of mail by the 1850s at up to three deliveries a day.

Coded Messages of Love

Postal deliveries were a big event for any household – rich or poor – so it was practically impossible to get mail to someone without the entire household knowing about it. At a time when ‘Victorian morals’ were central and privacy wasn’t, this made personal, private messaging between couples very difficult.

So, how did they speak their feelings without writing it?

They coded it into the positioning of their stamps.

Apparently the ‘secret stamp code’ actually emerged back in the ‘receiver pays’ mail era as a way to dodge exorbitant postal fees. The sender could encode a simple answer into the placement of their stamp on the envelope – perhaps ‘yes’, ‘no’, or ‘come at once’. The receiver could then examine the envelope, extract the message and then refuse to pay the delivery fee for the unopened letter.

Obviously, this became redundant in the ‘penny post’ era but later couples adopted the system for their own needs. Here’s an example.

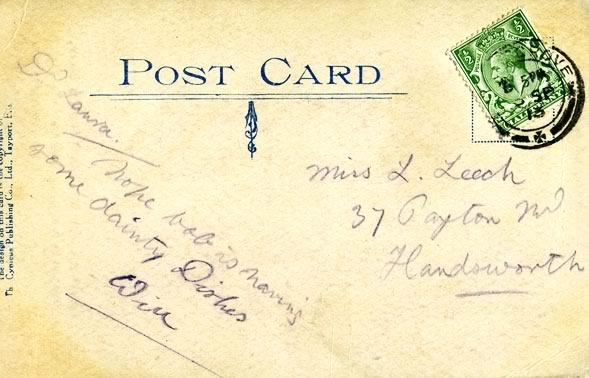

Will writes to Miss Laura Leech

The postcard above appears perfectly innocent to anyone scanning it. Will is asking Laura if “Bob is having some dainty dishes“. A little oblique – perhaps an ‘in-joke’ – but nothing improper.

In reality, the stamp tells another story. Will was telling Laura: “I’m longing to see you“. I hope that Bob wasn’t Laura’s husband.

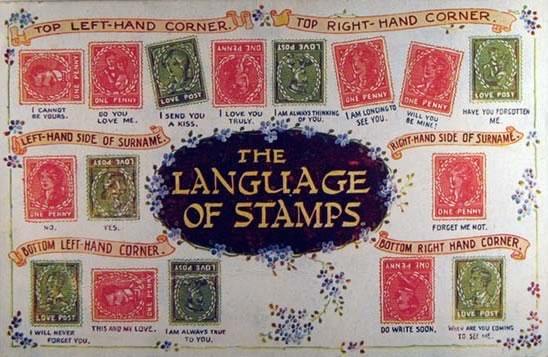

This stamp messaging system was used across the postal systems of the world although there was significant variation between countries. Some system relied on where the stamp was placed on the postcard while others were concerned only its orientation to the page.

The system was remarkably subtle and sophisticated. Messages could be as simple as ‘Yes’ or ‘No’ but also as complex as:

- “May I ask for your portrait?”

- “Take care. We’re being watched.”

- “I think you are very ungrateful.”

- “My heart is another’s”

- “I have discovered your deceipt.”

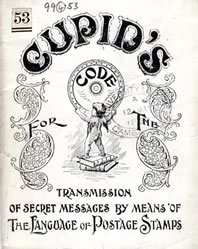

In fact, the introduction page in one ‘how-to’ booklet claimed to be able to encode 270,000 message variations. It makes you wonder if we really need the full alphabet anymore.

Of course, postcard companies often saw the code as a great opportunity to sell more postcards. They printed millions of these stamp messaging guides from the 1890s onward, though there was never a centralized body standardizing the code from region to region. Variation and mutation happen naturally.

As a consequence, some guides prescribe that a 90º right-turned stamp means a hopeful “Reply at once!“, while other guides would interpret the same stamp as “I wish for your friendship, but no more“.

I suspect there must have been thousands of star-crossed lovers who’s dreams were dashed by a misread coded message from a potential partner. Who would have thought that the mundane act of attaching a stamp to a letter could be loaded with such social danger?

You have to LOL, right?

Originally published in the SitePoint Design Newsletter.