Managing the CSS Box Model

Perhaps the most important point to understand about CSS is this: Everything is a box. More specifically, every element in a document generates a box. This box may be a block-level box, or it may be an inline-level box. The box type determines how the element affects page layout.

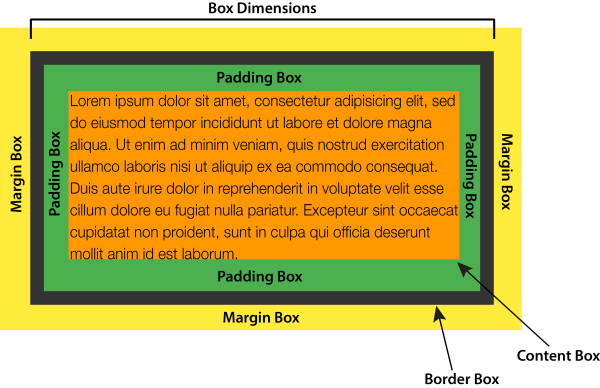

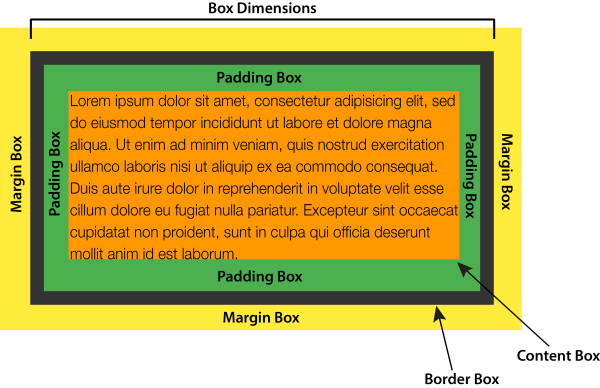

The CSS Box Model is a concept used to describe the layout and sizing of HTML elements. Each element contains a box for its content, padding, border, and margin. The boxes combine to determine an element’s layout of content as well as how adjacent elements appear alongside it:

Whether or not an element creates a box and which type of box it creates will depend on the markup language. CSS developed as a way to style HTML documents so, as a result, much of the CSS visual rendering model is rooted in HTML’s distinction between block-level and inline elements. By default, elements such as p and section create block-level boxes but a, span, and em create inline boxes. SVG, on the other hand, does not use the box model, so most layout-related CSS properties fail to work with SVG.

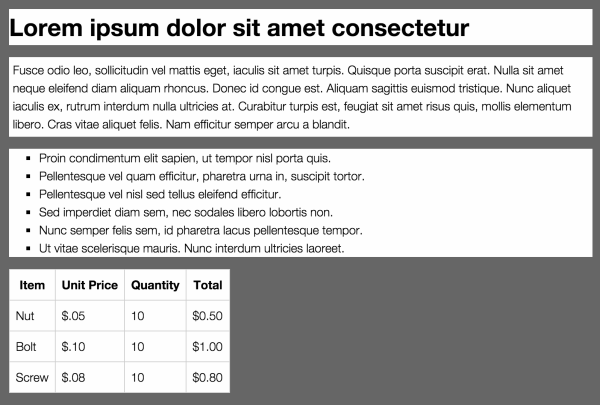

Block-level boxes create new blocks of content as can be seen in Figure 4.1. Block-level boxes are rendered vertically according to their source order and (except for tables) expand to fill the available width of their containing element. This is known as normal flow. Block-level boxes have a display value of block, list-item, table, or any of the table-* values (for example, table-cell).

Figure 4.1. Block-level boxes featuring h1, p, ul, and table elements within a containing element (gray area)

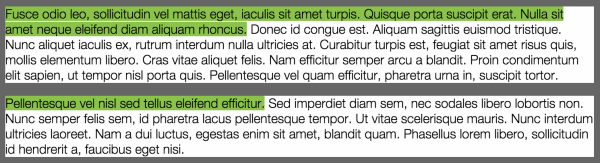

Inline-level boxes, by contrast, do not form new blocks of content. Instead, these boxes make up the lines inside a block box. They’re displayed horizontally and fill the width of the containing box, wrapping across lines if necessary, as shown in Figure 4.2. Inline-level boxes have a display value of inline, inline-block, inline-table, or ruby.

Figure 4.2. An example of an inline box with margin: 1em and padding: 5px applied

But how are the dimensions of the box calculated? Here is where it becomes more complicated. As seen in Figure 4.3, box dimensions are the sum of the box’s content area, plus its padding width, and border width. The margin width creates a margin box for the element, and affects other elements in the document; however, the margin width has no effect on the dimensions of the box itself.

Figure 4.3. The CSS 2.1 box model

For instance, a p element with width: 300px, padding: 20px, and border: 10px has a calculated width of 360 pixels. That’s the sum of its width, left and right padding, and left and right border-width properties. To create an element that is 300 pixels wide with 20 pixels of padding and a 10 pixel border, the width needs to be 240px. Most leading browsers calculated the width in just this way.

Partly as a way to resolve competing models of browsers, the CSS working group introduced the box-sizing property. It lets us choose the box model implementation that we prefer, and greatly simplifies calculations when working with responsive designs.

Choosing a Box Model with box-sizing

The box-sizing property is defined in the CSS Basic User Interface Module Level 3 specification. It has two possible values: content-box and border-box.

Initially, the value of box-sizing is content-box. With this value, setting the width and height properties of an element affect the size of its content area. This matches the behavior defined by the CSS 2.1 specification, and it’s the default behavior in modern browsers (as presented in Figure 4.4).

Setting the value of box-sizing to border-box creates a little bit of magic. Now, the values of width and height will be applied to the outer border edge instead of the content area. Borders and padding are drawn inside the element box, matching the old Internet Explorer 5.5 behavior. Let’s look at an example that mixes percentage widths and px units for padding and borders:

<div class="wrapper">

<article>

<h2>This is a headline</h2>

<p>Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipisicing ... </p>

</article>

<aside>

<h2>This is a secondary headline</h2>

<p>Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipisicing ... </p>

</aside>

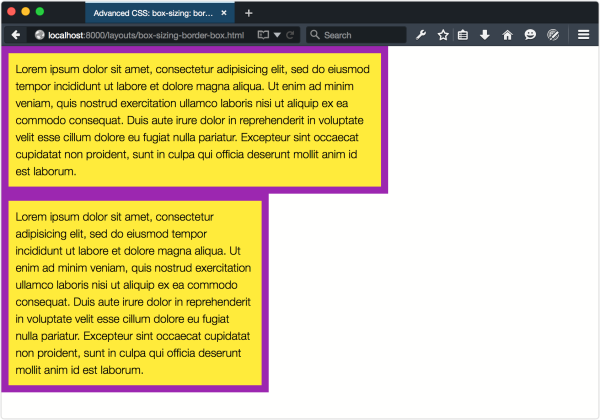

</div>Both our article and aside elements have the following CSS applied, which gives us the layout shown in Figure 4.5 where the first element has a width of 60% while the second has a width of 40%:

article, aside {

background: #FFEB3B;

border: 10px solid #9C27B0;

float: left;

padding: 10px;

}

article {

width: 60%;

}

aside {

width: 40%;

}

Figure 4.5. Elements with box-sizing: content-box

By default, both aside and article have a box-sizing value of content-box. The border-width and padding values add 40 pixels to the width of each element, which throws off the 60%/40% split considerably. Now let’s add box-sizing: border-box to the article and aside elements:

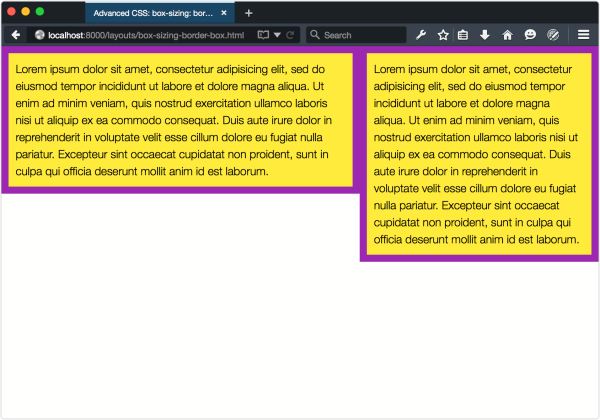

article, aside {

box-sizing: border-box;

}You can see the change in Figure 4.6: the elements have the same width, but the box-sizing: border-box means that the width includes the border and padding. Because the width property applies to the border edge instead of the content area, our elements now fit side by side.

Figure 4.6. Elements with box-sizing: border-box.

I’d suggest that you use box-sizing: border-box in your projects. It makes life easier, as there’s no need to calculate the width value to account for the values of padding and border, and boxes behave more predictably.

The best way to apply box-sizing: border-box is with reset rules. The following example is from Chris Coyier’s CSS-Tricks post, Inheriting box-sizing Probably Slightly Better Best-Practice:

html {

box-sizing: border-box;

}

*, *:before, *:after {

box-sizing: inherit;

}This applies border-box sizing to every element by default, without affecting the box-sizing behavior of existing parts of your project. If you know that there will be no third-party or legacy components that rely on content-box behavior, you can simplify these rules:

*,

*:before,

*:after {

box-sizing: border-box;

}Managing the box model is just one ingredient in understanding how to create complex layouts.