CSS Selectors: Combinators

CSS rules are matched to elements with selectors. There are a number of ways to do this, and you’re probably familiar with most of them. Element type, class name, ID, and attribute selectors are all well-supported CSS selectors and widely used.

The Selectors Level 3 and Level 4 specifications introduced several new selectors. In some cases, these are new variations of existing types. In other cases, they are new features of the language.

In this chapter, we’ll look at the current browser landscape for CSS selectors, with a focus on newer selectors. This includes new attribute selectors and combinators, and a range of new pseudo-classes. In the section Choosing Selectors Wisely, we look at the concept of specificity.

This chapter stops short of being a comprehensive look at all selectors―that could be a book unto itself. Instead, we’ll focus on selectors with good browser support that are likely to be useful in your current work. Some material may be old hat, but it’s included for context.

Tip: Browser Coverage for Selectors

A comprehensive look at the current state of browser support for selectors can be found at CSS4-Selectors.

The following is an extract from our book, CSS Master, written by Tiffany B. Brown. Copies are sold in stores worldwide, or you can buy it in ebook form here.

Combinators

Combinators are character sequences that express a relationship between the selectors on either side of it. Using a combinator creates what’s known as a complex selector. Complex selectors can, in some cases, be the most concise way to define styles.

You should be familiar with most of these combinators:

-

descendant combinator, or whitespace character

-

child combinator, or

> -

adjacent sibling combinator, or

+ -

general sibling combinator, or

~

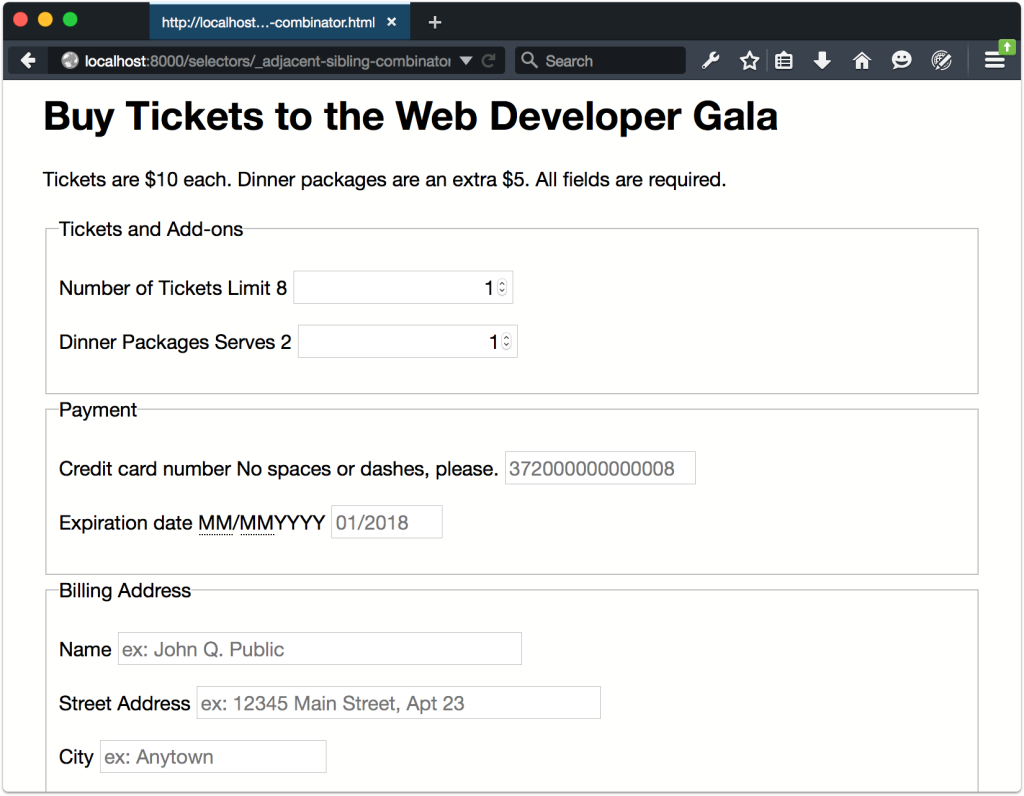

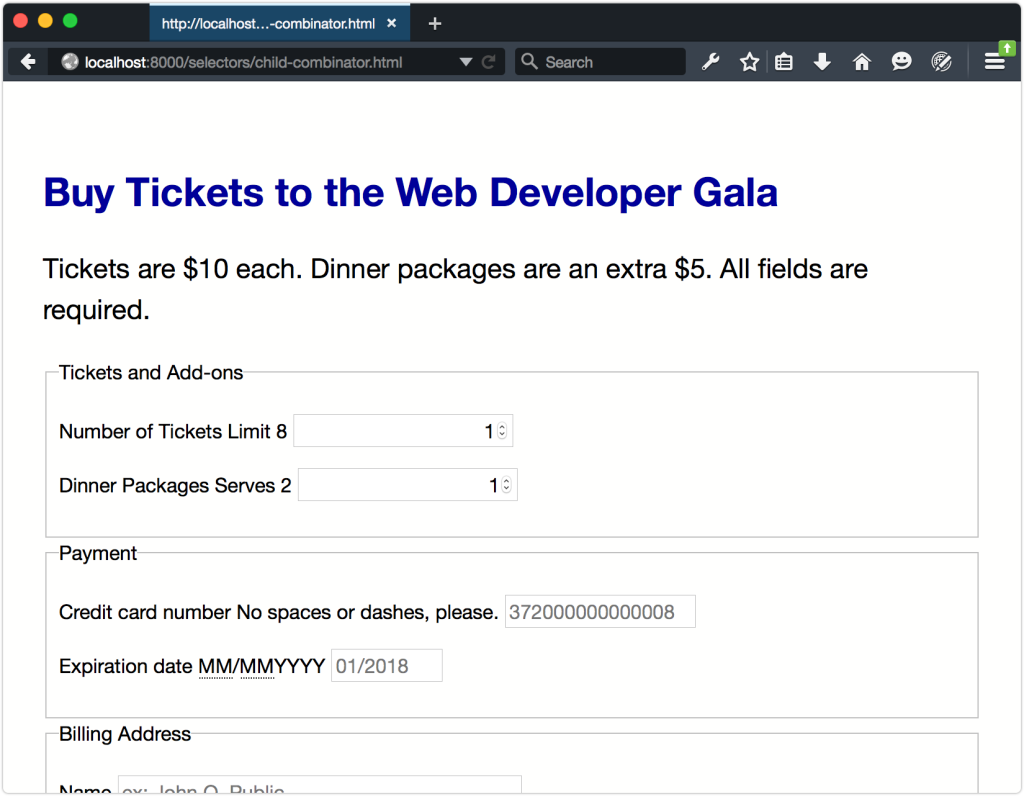

Let’s illustrate each of these combinators. We’ll use them to add styles to the HTML form shown below.

This form was created using the following chunk of HTML:

<form method="GET" action="/processor">

<h1>Buy Tickets to the Web Developer Gala</h1>

<p>Tickets are $10 each. Dinner packages are an extra $5. All fields are required.</p>

<fieldset>

<legend>Tickets and Add-ons</legend>

<p>

<label for="quantity">Number of Tickets</label>

<span class="help">Limit 8</span>

<input type="number" value="1" name="quantity" id="quantity" step="1" min="1" max="8">

</p>

<p>

<label for="quantity">Dinner Packages</label>

<span class="help">Serves 2</span>

<input type="number" value="1" name="quantity" id="quantity" step="1" min="1" max="8">

</p>

</fieldset>

<fieldset>

<legend>Payment</legend>

<p>

<label for="ccn">Credit card number</label>

<span class="help">No spaces or dashes, please.</span>

<input type="text" id="ccn" name="ccn" placeholder="372000000000008" maxlength="16" size="16">

</p>

<p>

<label for="expiration">Expiration date</label>

<span class="help"><abbr title="Two-digit month">MM</abbr>/<abbr title="Four-digit Year">MM</abbr>YYYY</span>

<input type="text" id="expiration" name="expiration" placeholder="01/2018" maxlength="7" size="7">

</p>

</fieldset>

<fieldset>

<legend>Billing Address</legend>

<p>

<label for="name">Name</label>

<input type="text" id="name" name="name" placeholder="ex: John Q. Public" size="40">

</p>

<p>

<label for="street_address">Street Address</label>

<input type="text" id="name" name="name" placeholder="ex: 12345 Main Street, Apt 23" size="40">

</p>

<p>

<label for="city">City</label>

<input type="text" id="city" name="city" placeholder="ex: Anytown">

</p>

<p>

<label for="state">State</label>

<input type="text" id="state" name="state" placeholder="CA" maxlength="2" pattern="[A-W]{2}" size="2">

</p>

<p>

<label for="zip">ZIP</label>

<input type="text" id="zip" name="zip" placeholder="12345" maxlength="5" pattern="0-9{5}" size="5">

</p>

</fieldset>

<button type="submit">Buy Tickets!</button>

</form>The Descendant Combinator

You’re probably quite familiar with the descendant combinator. It’s been around since the early days of CSS (though it was without a type name until CSS2.1). It’s widely used and widely supported.

The descendant combinator is just a whitespace character. It separates the parent selector from its descendant, following the pattern A B, where B is an element contained by A. Let’s add some CSS to our markup from above and see how this works:

form h1 {

color: #009;

}We’ve just changed the color of our form title, the result of which can be seen below.

Let’s add some more CSS, this time to increase the size of our pricing message (“Tickets are $10 each”):

form p {

font-size: 22px;

}There’s a problem with this selector, however, as you can see below. We’ve actually increased the size of the text in all of our form’s paragraphs, which isn’t what we want. How can we fix this? Let’s try the child combinator.

The Child Combinator

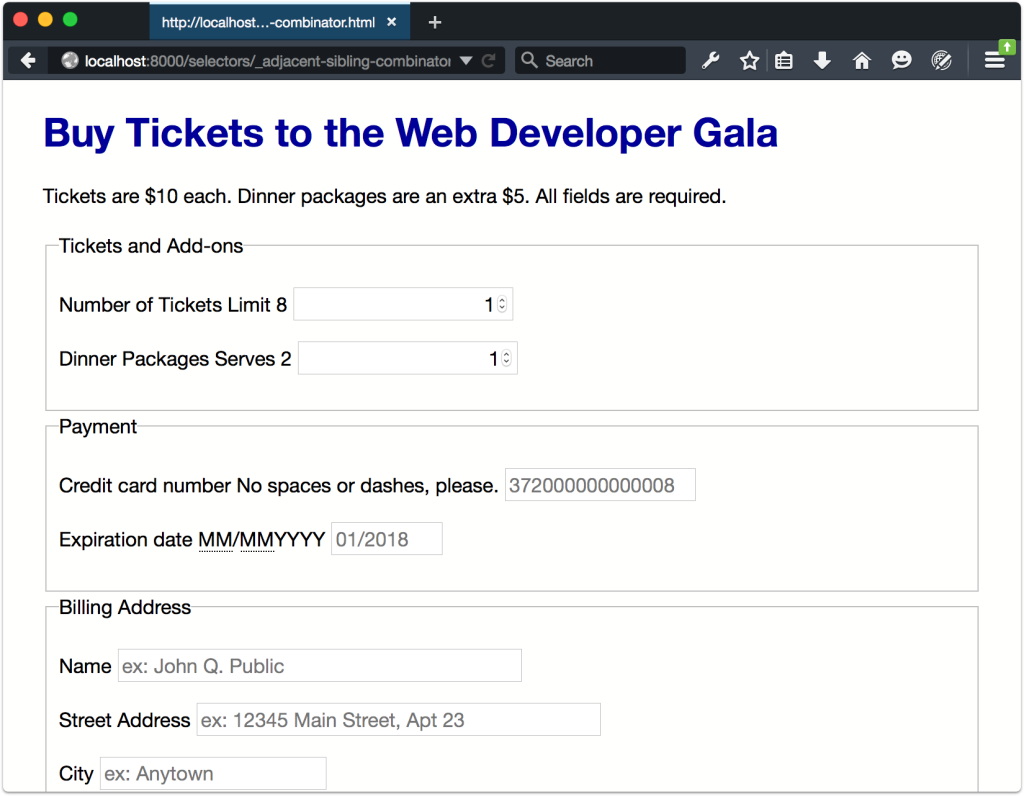

In contrast to the descendant combinator, the child combinator (>) selects only the immediate children of an element. It follows the pattern A > B, matching any element B where A is the immediate ancestor.

If elements were people, to use an analogy, the child combinator would match the child of the mother element. But the descendant combinator would also match her grandchildren, and great-grandchildren. Let’s modify our previous selector to use the child combinator:

form > p {

font-size: 22px;

}Now only the direct children of article are affected, as shown below.

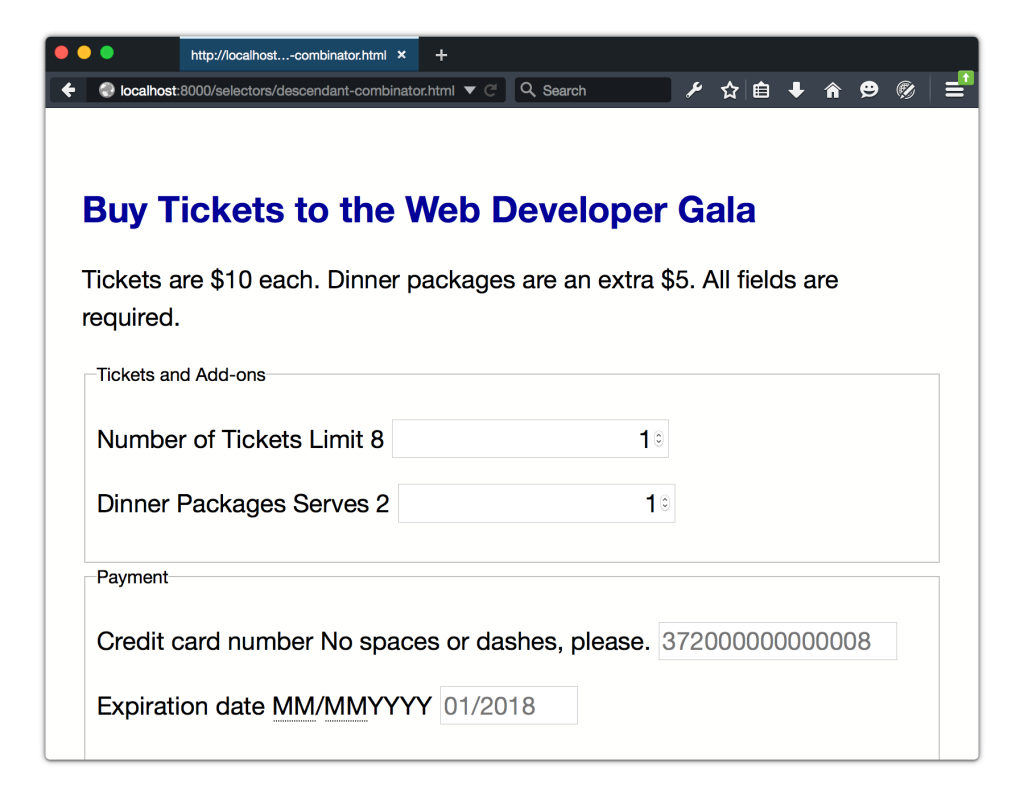

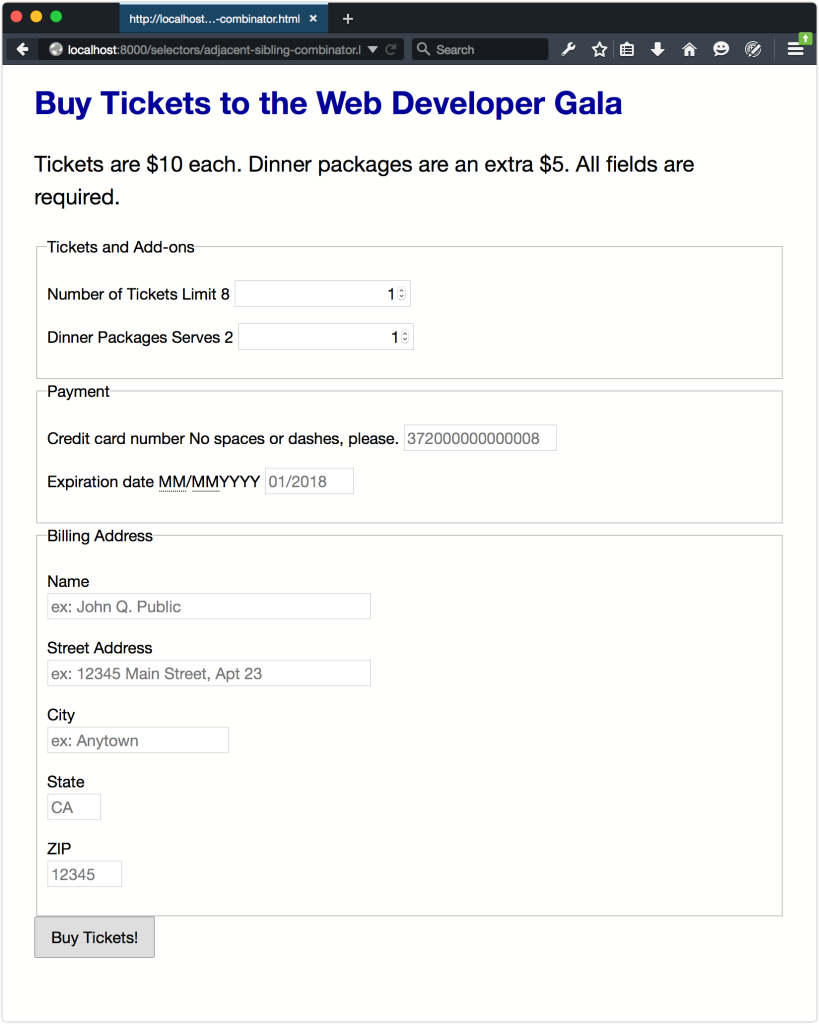

The Adjacent Sibling Combinator

With the adjacent sibling combinator (+), we can select elements that follow each other and have the same parent. It follows the pattern A + B. Styles will be applied to B elements that are immediately preceded by A elements.

Let’s go back to our example. Notice that our labels and inputs sit next to each other. That means we can use the adjacent sibling combinator to make them sit on separate lines:

label + input {

display: block;

clear: both;

}You can see the results below.

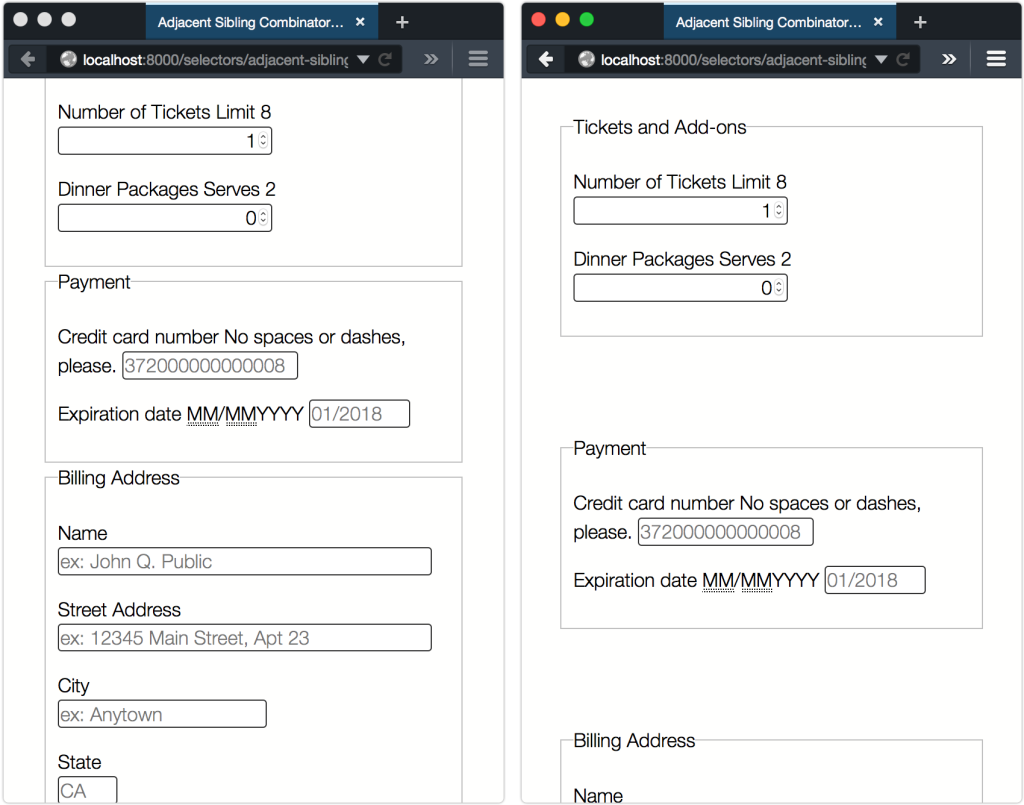

Let’s look at another example that combines the universal selector (*) with a type selector:

* + fieldset {

margin: 5em 0;

}This example adds a 5em margin to the top and bottom of every fieldset element, shown below. Since we’re using the universal selector, there’s no need to worry about whether the previous element is another fieldset or p element.

Note: More Uses of the Adjacent Sibling Selector

Heydon Pickering explores more clever uses of the adjacent sibling selector in his article “Axiomatic CSS and Lobotomized Owls.”

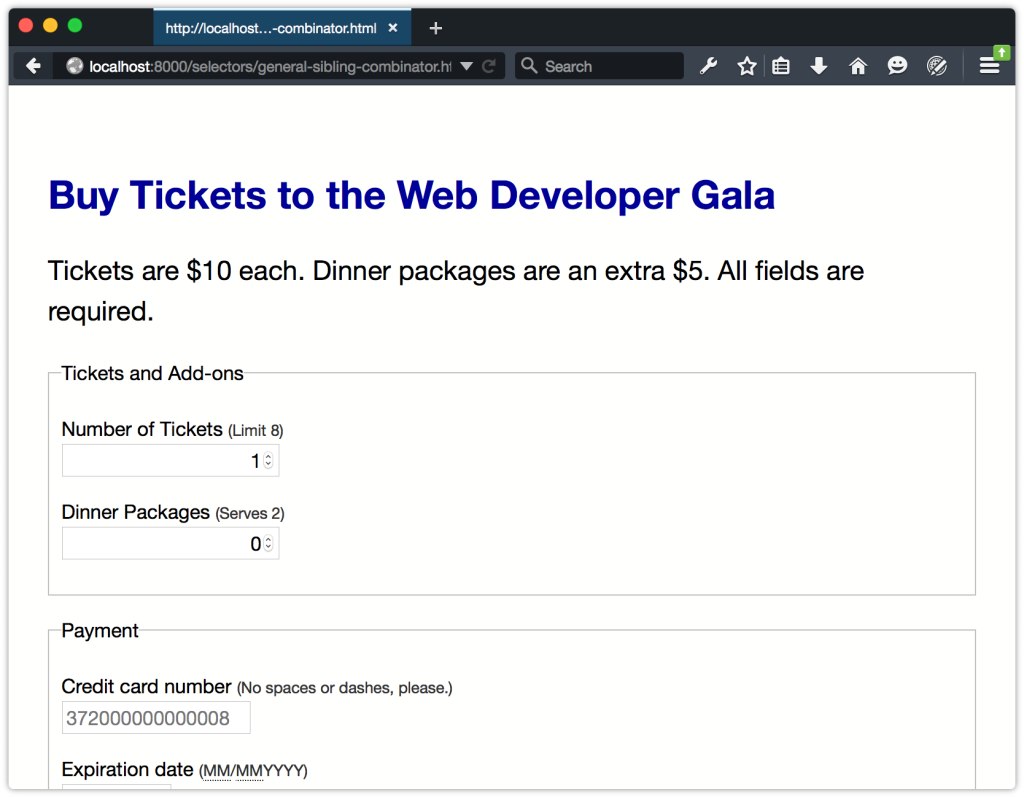

What if we want to style a sibling element that isn’t adjacent to another, as with our Number of Tickets field? In this case, we can use the general sibling combinator.

The General Sibling Combinator

With the general sibling combinator―a tilde―we can select elements that share the same parent without considering whether they’re adjacent. Given the pattern A ~ B, this selector matches all B elements that are preceded by an A element, whether or not they’re adjacent.

Let’s look at the Number of Tickets field again. Its markup looks like this:

<p>

<label for="quantity">Number of Tickets</label>

<span class="help">Limit 8</span>

<input type="number" value="1" name="quantity" id="quantity" step="1" min="1" max="8">

</p>Our input element follows the label element, but there is a span element in between. Since a span element sits between input and label, the adjacent sibling combinator will fail to work here. Let’s change our adjacent sibling combinator to a general sibling combinator:

label ~ input {

display: block;

}Now all of our input elements sit on a separate line from their label elements, as seen below.

Using the general sibling combinator is the most handy when you lack full control over the markup. Otherwise, you’d be better off adjusting your markup to add a class name. Keep in mind that the general sibling combinator may create some unintended side effects in a large code base, so use with care.