Game AI: The Bots Strike Back!

The following is a short extract taken from our new book, HTML5 Games: Novice to Ninja, written by Earle Castledine. Access to the book is included with SitePoint Premium membership, or you can grab a copy in stores worldwide. You can check out a free sample of the first chapter here.

We have all the tools at our disposal now to make fantastically detailed worlds to explore and inhabit. Unfortunately, our co-inhabitants haven’t proved themselves to be very worthy opponents. They’re dumb: they show no emotion, no thought, no anima. We can instill these characteristics via graphics, animation, and above all, artificial intelligence (AI).

Artificial intelligence is a huge and extremely complex field. Luckily, we can get impressive results even with a lot more artificial than intelligence. A couple of simple rules (combined with our old friend Math.random) can give a passable illusion of intention and thought. It doesn’t have to be overly realistic as long as it supports our game mechanics and is fun.

Like collision detection, AI is often best when it’s not too good. Computer opponents are superhuman. They have the gift of omniscience and can comprehend the entire state of the world at every point in time. The poor old human player is only able to see what’s visible on the screen. They’re generally no match against a computer.

But we don’t let them know that! They’d feel bad, question the future of humanity, and not want to play our games. As game designers, it’s our job to balance and dictate the flow of our games so that they’re always fair, challenging, and surprising to the player.

Intentional Movement

Choosing how sprites move around in the game is great fun. The update function is your blank canvas, and you get godlike control over your entities. What’s not to like about that!

The way an entity moves is determined by how much we alter its x and y position every frame (“move everything a tiny bit!”). So far, we’ve moved things mostly in straight lines with pos.x += speed * dt. Adding the speed (times the delta) causes the sprite to move to the right. Subtracting moves it to the left. Altering the y coordinate moves it up and down.

To make straight lines more fun, inject a bit of trigonometry. Using pos.y += Math.sin(t * 10) * 200 * dt, the sprite bobs up and down through a sine wave. t * 10 is the frequency of the wave. t is the time in seconds from our update system, so it’s always increasing linearly. Giving that to Math.sin produces a smooth sine wave. Changing the multiplier will alter the frequency: a lower number will oscillate faster. 200 is the amplitude of the waves.

You can combine waves to get even more interesting results. Say you added another sine wave to the y position: pos.y += Math.sin(t * 11) * 200 * dt. It’s almost exactly the same as the first, but the frequency is altered very slightly. Now, as the two waves reinforce and cancel each other out as they drift in and out of phase, the entity bobs up and down faster and slower. Shifting the frequency and amplitude a lot can give some interesting bouncing patterns. Alter the x position with Math.cos and you have circles.

The important aspect of this is that movements can be combined to make more complex-looking behaviors. They can move spasmodically, they can drift lazily. As we go through this chapter, they’ll be able to charge directly towards a player, or to run directly away. They’ll be able to traverse a maze. When you combine these skills (a bobbing motion used in conjunction with a charge-at-player), or sequence them (run away for two seconds, then bob up and down for one second) they can be sculpted into very lifelike beings.

Waypoints

We need to spice up these apathetic ghosts and bats, giving them something to live for. We’ll start with the concept of a “waypoint”. Waypoints are milestones or intermediate target locations that the entity will move towards. Once they arrive at the waypoint, they move on to the next, until they reach their destination. A carefully placed set of waypoints can provide the game character with a sense of purpose, and can be used to great effect in your level design.

So that we can concentrate on the concepts behind waypoints, we’ll introduce a flying bad guy who’s not constrained by the maze walls. The scariest flying enemy is the mosquito (it’s the deadliest animal in the world, after humans). But not very spooky. We’ll go with “bat”.

Bats won’t be complex beasts; they’ll be unpredictable. They’ll simply have a single waypoint they fly towards. When they get there, they’ll pick a new waypoint. Later (when we traverse a maze) we’ll cover having multiple, structured waypoints. For now, bats waft from point to point, generally being a nuisance to the player.

To create them, make a new entity based on a TileSprite, called Bat, in entities/Bat.js. The bats need some smarts to choose their desired waypoint. That might be a function that picks a random location anywhere on screen, but to make them a bit more formidable we’ll give them the findFreeSpot functions, so the waypoint will always be a walkable tile where the player might be traveling:

const bats = this.add(new Container());

for (let i = 0; i < 5; i++) {

bats.add(new Bat(() => map.findFreeSpot()))

}

We have a new Container for the bats, and we create five new ones. Each gets a reference to our waypoint-picking function. When called, it runs map.findFreeSpot and finds an empty cell in the maze. This becomes the bat’s new waypoint:

class Bat extends TileSprite {

constructor(findWaypoint) {

super(texture, 48, 48);

this.findWaypoint = findWaypoint;

this.waypoint = findWaypoint();

...

}

}

Inside Bat.js we assign an initial goal location, then in the bat’s update method we move towards it. Once we’re close enough, we choose another location to act as the next waypoint:

// Move in the direction of the path

const xo = waypoint.x - pos.x;

const yo = waypoint.y - pos.y;

const step = speed * dt;

const xIsClose = Math.abs(xo) <= step;

const yIsClose = Math.abs(yo) <= step;

How do we “move towards” something, and how do we know if we’re “close enough”? To answer both of these questions, we’ll first find the difference between the waypoint location and the bat. Subtracting the x and y values of the waypoint from the bat’s position gives us the distance on each axis. For each axis we define “close enough” to mean Math.abs(distance) <= step. Using step (which is based on speed) means that the faster we’re traveling, the further we need to be to be “close enough” (so we don’t overshoot forever).

Note: Take the absolute value of the distance, as it could be negative if we’re on the other side of the waypoint. We don’t care about direction, only distance.

if (!xIsClose) {

pos.x += speed * (xo > 0 ? 1 : -1) * dt;

}

if (!yIsClose) {

pos.y += speed * (yo > 0 ? 1 : -1) * dt;

}

To move in the direction of the waypoint, we’ll break movement into two sections. If we’re not too close in either the x or y directions, we move the entity towards the waypoint. If the ghost is above the waypoint (y > 0) we move it down, otherwise we move it up—and the same for the x axis. This doesn’t give us a straight line (that’s coming up when we start shooting at the player), but it does get us closer to the waypoint each frame.

if (xIsClose && yIsClose) {

// New way point

this.waypoint = this.findWaypoint();

}

Finally, if both horizontal and vertical distances are close enough, the bat has arrived at its destination and we reassign this.waypoint to a new location. Now the bats mindlessly roam the halls, as we might expect bats to do.

This is a very simple waypoint system. Generally, you’ll want a list of points that constitute a complete path. When the entity reaches the first waypoint, it’s pulled from the list and the next waypoint takes its place. We’ll do something very similar to this when we encounter path finding shortly.

Moving, and Shooting, Towards a Target

Think back to our first shoot-’em-up from Chapter 3. The bad guys simply flew from right to left, minding their own business—while we, the players, mowed down the mindless zombie pilots. To level the playing field and make things more interesting from a gameplay perspective, our foes should at least be able to fire projectiles at us. This gives the player an incentive to move around the screen, and a motive for destroying otherwise quite peaceful entities. Suddenly we’re the hero again.

Providing awareness of the player’s location to bad guys is pretty easy: it’s just player.pos! But how do we use this information to send things hurtling in a particular direction? The answer is, of course, trigonometry!

function angle (a, b) {

const dx = a.x - b.x;

const dy = a.y - b.y;

const angle = Math.atan2(dy, dx);

return angle;

}

Note: In this chapter, we’ll see a couple of trigonometric functions for achieving our immediate goals of “better bad guys”—but we won’t really explore how they work. This is the topic of next chapter … so if you’re a bit rusty on math, you can breathe easy for the moment.

In the same way we implemented math.distance, we first need to get the difference between the two points (dx and dy), and then we use the built-in arctangent math operator Math.atan2 to get the angle created between the two vectors. Notice that atan2 takes the y difference as the first parameter and x as the second. Add the angle function to utils/math.js.

Most of the time in our games, we’ll be looking for the angle between two entities (rather than points). So we’re usually interested in the angle between the center of the entities, not their top-left corners as defined by pos. We can also add an angle function to utils/entity.js, which first finds the two entities’ centers and then calls math.angle:

function angle(a, b) {

return math.angle(center(a), center(b));

}

The angle function returns the angle between the two positions, in radians. Using this information we can now calculate the amounts we have to modify an entity’s x and y position to move in the correct direction:

const angleToPlayer = entity.angle(player.pos, baddie.pos);

pos.x += Math.cos(angle) * speed * dt;

pos.y += Math.sin(angle) * speed * dt;

To use an angle in your game, remember that the cosine of an angle is how far along the x axis you need to move when moving one pixel in the angle direction. And the sine of an angle is how far along the y axis you need to move. Multiplying by a scalar (speed) number of pixels, the sprite moves in the correct direction.

Knowing the angle between two things turns out to be mighty important in gamedev. Commit this equation to memory, as you’ll use it a lot. For example, we can now shoot directly at things—so let’s do that! Create a Bullet.js sprite to act as a projectile:

class Bullet extends Sprite {

constructor(dir, speed = 100) {

super(texture);

this.speed = speed;

this.dir = dir;

this.life = 3;

}

}

A Bullet will be a small sprite that’s created with a position, a velocity (speed and direction), and a “life” (that’s defaulted to three seconds). When life gets to 0, the bullet will be set to dead … and we won’t end up with millions of bullets traveling towards infinity (exactly like our bullets from Chapter 3).

update(dt) {

const { pos, speed, dir } = this;

// Move in the direction of the path

pos.x += speed * dt * dir.x;

pos.y += speed * dt * dir.y;

if ((this.life -= dt) < 0) {

this.dead = true;

}

}

The difference from our Chapter 3 bullets is that they now move in the direction given when it was instantiated. Because x and y will represent the angle between two entities, the bullets will fire in a straight line towards the target—which will be us.

The bullets won’t just mysteriously appear out of thin air. Something needs to fire them. We need another new bad guy! We’ll deploy a couple of sentinels, in the form of top-hat totems. Totems are the guards of the dungeons who watch over the world from the center of the maze, destroying any treasure-stealing protagonists.

The Totem.js entity generates Bullets and fires them towards the Player. So they need a reference to the player (they don’t know it’s a player, they just think of it as the target) and a function to call when it’s time to generate a bullet. We’ll call that onFire and pass it in from the GameScreen so the Totem doesn’t need to worry itself about Bullets:

class Totem extends TileSprite {

constructor(target, onFire) {

super(texture, 48, 48);

this.target = target;

this.onFire = onFire;

this.fireIn = 0;

}

}

When a new Totem is created, it’s assigned a target, and given a function to call when it shoots a Bullet. The function will add the bullet into the main game container so it can be checked for collisions. Now Bravedigger must avoid Bats and Bullets. We’ll rename the container to baddies because the collision logic is the same for both:

new Totem(player, bullet => baddies.add(bullet)))

To get an entity on screen, it needs to go inside a Container to be included in our scene graph. There are many ways we could do this. We could make our main GameScreen object a global variable and call gameScreen.add from anywhere. This would work, but it’s not good for information encapsulation. By passing in a function, we can specify only the abilities we want a Totem to perform. As always, it’s ultimately up to you.

Warning: There’s a hidden gotcha in our Container logic. If we add an entity to a container during that container’s own update call, the entity will not be added! For example, if Totem was inside baddies and it tried to add a new bullet also to baddies, the bullet would not appear. Look at the code for Container and see if you can see why. We’ll address this issue in Chapter 9, in the section “Looping Over Arrays”.

When should the totem fire at the player? Randomly, of course! When it’s time to shoot, the fireIn variable will be set to a countdown. While the countdown is happening, the totem has a small animation (switching between two frames). In game design, this is called telegraphing—a subtle visual indication to the player that they had better be on their toes. Without telegraphing, our totems would suddenly and randomly shoot at the player, even when they’re really close. They’d have no chance to dodge the bullets and would feel cheated and annoyed.

if (math.randOneIn(250)) {

this.fireIn = 1;

}

if (this.fireIn > 0) {

this.fireIn -= dt;

// Telegraph to the player

this.frame.x = [2, 4][Math.floor(t / 0.1) % 2];

if (this.fireIn < 0) {

this.fireAtTarget();

}

}

There’s a one-in-250 chance every frame that the totem will fire. When this is true, a countdown begins for one second. Following the countdown, the fireAtTarget method will do the hard work of calculating the trajectory required for a projectile to strike a target:

fireAtTarget() {

const { target, onFire } = this;

const totemPos = entity.center(this);

const targetPos = entity.center(target);

const angle = math.angle(targetPos, totemPos);

...

}

The first steps are to get the angle between the target and the totem using math.angle. We could use the helper entity.angle (which does the entity.center calls for us), but we also need the center position of the totem to properly set the starting position of the bullet:

const x = Math.cos(angle);

const y = Math.sin(angle);

const bullet = new Bullet({ x, y }, 300);

bullet.pos.x = totemPos.x - bullet.w / 2;

bullet.pos.y = totemPos.y - bullet.h / 2;

onFire(bullet);

Once we have the angle, we use cosine and sine to calculate the components of the direction. (Hmm, again: perhaps you’d like to make that into another math function that does it for you?) Then we create a new Bullet that will move in the correct direction.

That suddenly makes maze traversal quite challenging! You should spend some time playing around with the “shoot-at” code: change the random interval chance, or make it a timer that fires consistently every couple of seconds … or a bullet-hell spawner that fires a volley of bullets for a short period of time.

Note: Throughout this book, we’ve seen many small mechanics that illustrate various concepts. Don’t forget that game mechanics are flexible. They can be reused and recombined with other mechanics, controls, or graphics to make even more game ideas—and game genres! For example, if you combine “mouse clicking” with “waypoints” and “fire towards”, we have a basic tower defense game! Create a waypoint path for enemies to follow: clicking the mouse adds a turret (that uses math.distance to find the closest enemy) and then fires toward it.

Smart Bad Guys: Attacking and Evading

Our bad guys have one-track minds. They’re given a simple task (fly left while shooting randomly; shoot towards player …) and they do the same thing in perpetuity, like some mindless automata. But real bad guys aren’t like that: they scheme, they wander, they idle, they have various stages of alertness, they attack, they retreat, they stop for ice cream …

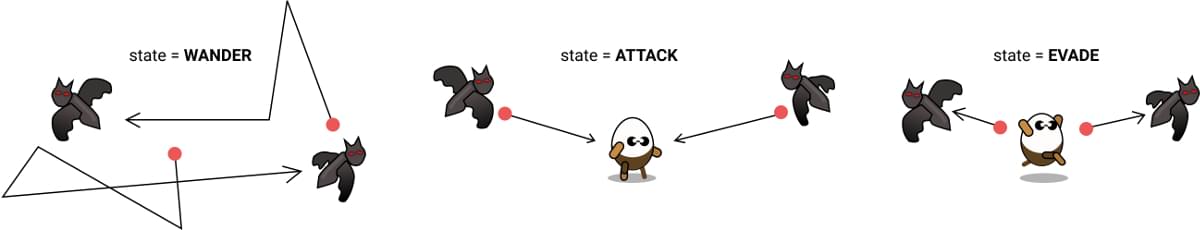

One way to model these desires is through a state machine. A state machine orchestrates behavior changes between a set number of states. Different events can cause a transition from the current state to a new state. States will be game-specific behaviors like “idle”, “walk”, “attack”, “stop for ice cream”. You can’t be attacking and stopping for ice cream. Implementing state machines can be as simple as storing a state variable that we restrict to one item out of a list. Here’s our initial list for possible bat states (defined in the Bat.js file):

const states = {

ATTACK: 0,

EVADE: 1,

WANDER: 2

};

Note: It’s not necessary to define the states in an object like this. We could just use the strings “ATTACK”, “EVADE”, and “WANDER”. Using an object like this just lets us organize our thoughts—listing all the possible states in one place—and our tools can warn us if we’ve made an error (like assigning a state that doesn’t exist). Strings are fine though!

At any time, a bat can be in only one of the ATTACK, EVADE, or WANDER states. Attacking will be flying at the player, evading is flying directly away from the player, and wandering is flitting around randomly. In the function constructor, we’ll assign the initial state of ATTACKing: this.state = state.ATTACK. Inside update we switch behavior based on the current state:

const angle = entity.angle(target, this);

const distance = entity.distance(target, this);

if (state === states.ATTACK) {

...

} else if (state === states.EVADE) {

...

} else if (state === states.WANDER) {

...

}

Depending on the current state (and combined with the distance and angle to the player) a Bat can make decisions on how it should act. For example, if it’s attacking, it can move directly towards the player:

xo = Math.cos(angle) * speed * dt;

yo = Math.sin(angle) * speed * dt;

if (distance < 60) {

this.state = states.EVADE;

}

But it turns out our bats are part chicken: when they get too close to their target (within 60 pixels), the state switches to state.EVADE. Evading works the same as attacking, but we negate the speed so they fly directly away from the player:

xo = -Math.cos(angle) * speed * dt;

yo = -Math.sin(angle) * speed * dt;

if (distance > 120) {

if (math.randOneIn(2)) {

this.state = states.WANDER;

this.waypoint = findFreeSpot();

} else {

this.state = states.ATTACK;

}

}

While evading, the bat continually considers its next move. If it gets far enough away from the player to feel safe (120 pixels), it reassesses its situation. Perhaps it wants to attack again, or perhaps it wants to wander off towards a random waypoint.

Combining and sequencing behaviors in this way is the key to making believable and deep characters in your game. It can be even more interesting when the state machines of various entities are influenced by the state of other entities—leading to emergent behavior. This is when apparent characteristics of entities magically appear—even though you, as the programmer, didn’t specifically design them.

Note: An example of this is in Minecraft. Animals are designed to EVADE after taking damage. If you attack a cow, it will run for its life (so hunting is more challenging for the player). Wolves in the game also have an ATTACK state (because they’re wolves). The unintended result of these state machines is that you can sometimes see wolves involved in a fast-paced sheep hunt! This behavior wasn’t explicitly added, but it emerged as a result of combining systems.

A More Stately State Machine

State machines are used a lot when orchestrating a game—not only in entity AI. They can control the timing of screens (such as “GET READY!” dialogs), set the pacing and rules for the game (such as managing cool-down times and counters) and are very helpful for breaking up any complex behavior into small, reusable pieces. (Functionality in different states can be shared by different types of entities.)

Dealing with all of these states with independent variables and if … else clauses can become unwieldy. A more powerful approach is to abstract the state machine into its own class that can be reused and extended with additional functionality (like remembering what state we were in previously). This is going to be used across most games we make, so let’s create a new file for it called State.js and add it to the Pop library:

class State {

constructor(state) {

this.set(state);

}

set(state) {

this.last = this.state;

this.state = state;

this.time = 0;

this.justSetState = true;

}

update(dt) {

this.first = this.justSetState;

this.justSetState = false;

...

}

}

The State class will hold the current and previous states, as well as remember how long we’ve been in the current state. It can also tell us if it’s the first frame we’ve been in the current state. It does this via a flag (justSetState). Every frame, we have to update the state object (the same way we do with our MouseControls) so we can do timing calculations. Here we also set the first flag if it’s the first update. This is useful for performing state initialization tasks, such as reseting counters.

if (state.first) {

// just entered this state!

this.spawnEnemy();

}

When a state is set (via state.set("ATTACK")), the property first will be set to true. Subsequent updates will reset the flag to false. The delta time is also passed into update so we can track the amount of time the current state has been active. If it’s the first frame, we reset the time to 0; otherwise, we add dt:

this.time += this.first ? 0 : dt;

We now can retrofit our chase-evade-wander example to use the state machine, and remove our nest of ifs:

switch (state.get()) {

case states.ATTACK:

break;

case states.EVADE:

break;

case states.WANDER:

break;

}

state.update(dt);

This is some nice documentation for the brain of our Bat—deciding what to do next given the current inputs. Because there’s a flag for the first frame of the state, there’s also now a nice place to add any initialization tasks. For example, when the Bat starts WANDERing, it needs to choose a new waypoint location:

case states.WANDER:

if (state.first) {

this.waypoint = findFreeSpot();

}

...

break;

}

It’s usually a good idea to do initialization tasks in the state.first frame, rather than when you transition out of the previous frame. For example, we could have set the waypoint as we did state.set("WANDER"). If state logic is self-contained, it’s easier to test. We could default a Bat to this.state = state.WANDER and know the waypoint will be set in the first frame of the update.

There are a couple of other handy functions we’ll add to State.js for querying the current state:

is(state) {

return this.state === state;

}

isIn(...states) {

return states.some(s => this.is(s));

}

Using these helper functions, we can conveniently find out if we’re in one or more states:

if (state.isIn("EVADE", "WANDER")) {

// Evading or wandering - but not attacking.

}

The states we choose for an entity can be as granular as needed. We might have states for “BORN” (when the entity is first created), “DYING” (when it’s hit, and stunned), and “DEAD” (when it’s all over), giving us discrete locations in our class to handle logic and animation code.

Controlling Game Flow

State machines are useful anywhere you need control over a flow of actions. One excellent application is to manage our high-level game state. When the dungeon game commences, the user shouldn’t be thrown into a hectic onslaught of monsters and bullets flying around out of nowhere. Instead, a friendly “GET READY” message appears, giving the player a couple of seconds to survey the situation and mentally prepare for the mayhem ahead.

A state machine can break the main logic in the GameScreen update into pieces such as “READY”, “PLAYING”, “GAMEOVER”. It makes it clearer how we should structure our code, and how the overall game will flow. It’s not necessary to handle everything in the update function; the switch statement can dispatch out to other methods. For example, all of the code for the “PLAYING” state could be grouped in an updatePlaying function:

switch(state.get()) {

case "READY":

if (state.first) {

this.scoreText.text = "GET READY";

}

if (state.time > 2) {

state.set("PLAYING");

}

break;

case "PLAYING":

if (entity.hit(player, bat)) {

state.set("GAMEOVER");

}

break;

case "GAMEOVER":

if (controls.action) {

state.set("READY");

}

break;

}

state.update(dt);

The GameScreen will start in the READY state, and display the message “GET READY”. After two seconds (state.time > 2) it transitions to “PLAYING” and the game is on. When the player is hit, the state moves to “GAMEOVER”, where we can wait until the space bar is pressed before starting over again.