How the CSS :is, :where and :has Pseudo-class Selectors Work

CSS selectors allow you to choose elements by type, attributes, or location within the HTML document. This tutorial explains three new options — :is(), :where(), and :has().

Selectors are commonly used in stylesheets. The following example locates all <p> paragraph elements and changes the font weight to bold:

p {

font-weight: bold;

}

You can also use selectors in JavaScript to locate DOM nodes:

- document.querySelector() returns the first matching HTML element

- document.querySelectorAll() returns all matching HTML elements in an array-like NodeList

Pseudo-class selectors target HTML elements based on their current state. Perhaps the most well known is :hover, which applies styles when the cursor moves over an element, so it’s used to highlight clickable links and buttons. Other popular options include:

:visited: matches visited links:target: matches an element targeted by a document URL:first-child: targets the first child element:nth-child: selects specific child elements:empty: matches an element with no content or child elements:checked: matches a toggled-on checkbox or radio button:blank: styles an empty input field:enabled: matches an enabled input field:disabled: matches a disabled input field:required: targets a required input field:valid: matches a valid input field:invalid: matches an invalid input field:playing: targets a playing audio or video element

Browsers have recently received three more pseudo-class selectors…

The CSS :is Pseudo-class Selector

Note: this was originally specified as :matches() and :any(), but :is() has become the CSS standard.

You often need to apply the same styling to more than one element. For example, <p> paragraph text is black by default, but gray when it appears within an <article>, <section>, or <aside>:

/* default black */

p {

color: #000;

}

/* gray in <article>, <section>, or <aside> */

article p,

section p,

aside p {

color: #444;

}

This is a simple example, but more sophisticated pages will lead to more complicated and verbose selector strings. A syntax error in any selector could break styling for all elements.

CSS preprocessors such as Sass permit nesting (which is also coming to native CSS):

article, section, aside {

p {

color: #444;

}

}

This creates identical CSS code, reduces typing effort, and can prevent errors. But:

- Until native nesting arrives, you’ll need a CSS build tool. You may want to use an option like Sass, but that can introduce complications for some development teams.

- Nesting can cause other problems. It’s easy to construct deeply nested selectors that become increasingly difficult to read and output verbose CSS.

:is() provides a native CSS solution which has full support in all modern browsers (not IE):

:is(article, section, aside) p {

color: #444;

}

A single selector can contain any number of :is() pseudo-classes. For example, the following complex selector applies a green text color to all <h1>, <h2>, and <p> elements that are children of a <section> which has a class of .primary or .secondary and which isn’t the first child of an <article>:

article section:not(:first-child):is(.primary, .secondary) :is(h1, h2, p) {

color: green;

}

The equivalent code without :is() required six CSS selectors:

article section.primary:not(:first-child) h1,

article section.primary:not(:first-child) h2,

article section.primary:not(:first-child) p,

article section.secondary:not(:first-child) h1,

article section.secondary:not(:first-child) h2,

article section.secondary:not(:first-child) p {

color: green;

}

Note that :is() can’t match ::before and ::after pseudo-elements, so this example code will fail:

/* NOT VALID - selector will not work */

div:is(::before, ::after) {

display: block;

content: '';

width: 1em;

height: 1em;

color: blue;

}

The CSS :where Pseudo-class Selector

:where() selector syntax is identical to :is() and is also supported in all modern browsers (not IE). It will often result in identical styling. For example:

:where(article, section, aside) p {

color: #444;

}

The difference is specificity. Specificity is the algorithm used to determine which CSS selector should override all others. In the following example, article p is more specific than p alone, so all paragraph elements within an <article> will be gray:

article p { color: #444; }

p { color: #000; }

In the case of :is(), the specificity is the most specific selector found within its arguments. In the case of :where(), the specificity is zero.

Consider the following CSS:

article p {

color: black;

}

:is(article, section, aside) p {

color: red;

}

:where(article, section, aside) p {

color: blue;

}

Let’s apply this CSS to the following HTML:

<article>

<p>paragraph text</p>

</article>

The paragraph text will be colored red, as shown in the following CodePen demo.

See the Pen

Using the :is selector by SitePoint (@SitePoint)

on CodePen.

The :is() selector has the same specificity as article p, but it comes later in the stylesheet, so the text becomes red. It’s necessary to remove both the article p and :is() selectors to apply a blue color, because the :where() selector is less specific than either.

More codebases will use :is() than :where(). However, the zero specificity of :where() could be practical for CSS resets, which apply a baseline of standard styles when no specific styling is available. Typically, resets apply a default font, color, paddings and margins.

This CSS reset code applies a top margin of 1em to <h2> headings unless they’re the first child of an <article> element:

/* CSS reset */

h2 {

margin-block-start: 1em;

}

article :first-child {

margin-block-start: 0;

}

Attempting to set a custom <h2> top margin later in the stylesheet has no effect, because article :first-child has a higher specificity:

/* never applied - CSS reset has higher specificity */

h2 {

margin-block-start: 2em;

}

You can fix this using a higher-specificity selector, but it’s more code and not necessarily obvious to other developers. You’ll eventually forget why you required it:

/* styles now applied */

article h2:first-child {

margin-block-start: 2em;

}

You can also fix the problem by applying !important to each style, but please avoid doing that! It makes further styling and development considerably more challenging:

/* works but avoid this option! */

h2 {

margin-block-start: 2em !important;

}

A better choice is to adopt the zero specificity of :where() in your CSS reset:

/* reset */

:where(h2) {

margin-block-start: 1em;

}

:where(article :first-child) {

margin-block-start: 0;

}

You can now override any CSS reset style regardless of the specificity; there’s no need for further selectors or !important:

/* now works! */

h2 {

margin-block-start: 2em;

}

The CSS :has Pseudo-class Selector

The :has() selector uses a similar syntax to :is() and :where(), but it targets an element which contains a set of others. For example, here’s the CSS for adding a blue, two-pixel border to any <a> link that contains one or more <img> or <section> tags:

/* style the <a> element */

a:has(img, section) {

border: 2px solid blue;

}

This is the most exciting CSS development in decades! Developers finally have a way to target parent elements!

The elusive “parent selector” has been one of the most requested CSS features, but it raises performance complications for browser vendors, and therefor has been a long time coming. In simplistic terms:

- Browsers apply CSS styles to an element when it’s drawn on the page. The whole parent element must therefore be re-drawn when adding further child elements.

- Adding, removing, or modifying elements in JavaScript could affect the styling of the whole page right up to the enclosing

<body>.

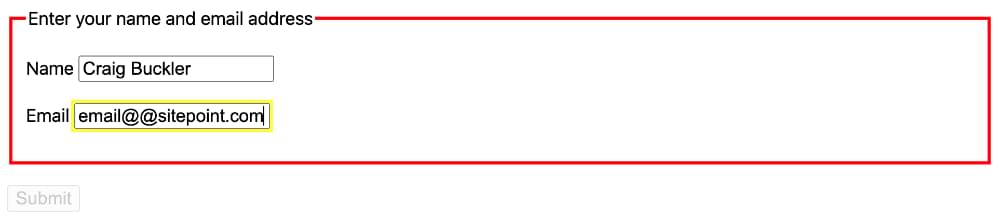

Assuming the vendors have resolved performance issues, the introduction of :has() permits possibilities that would have been impossible without JavaScript in the past. For example, you can set the styles of an outer form <fieldset> and the following submit button when any required inner field is not valid:

/* red border when any required inner field is invalid */

fieldset:has(:required:invalid) {

border: 3px solid red;

}

/* change submit button style when invalid */

fieldset:has(:required:invalid) + button[type='submit'] {

opacity: 0.2;

cursor: not-allowed;

}

This example adds a navigation link submenu indicator that contains a list of child menu items:

/* display sub-menu indicator */

nav li:has(ol, ul) a::after {

display: inlne-block;

content: ">";

}

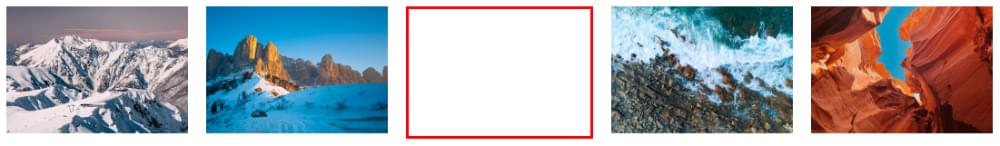

Or perhaps you could add debugging styles, such as highlighting all <figure> elements without an inner img:

/* where's my image?! */

figure:not(:has(img)) {

border: 3px solid red;

}

Before you jump into your editor and refactor your CSS codebase, please be aware that :has() is new and support is more limited than for :is() and :where(). It’s available in Safari 15.4+ and Chrome 101+ behind an experimental flag, but it should be widely available by 2023.

Selector Summary

The :is() and :where() pseudo-class selectors simplify CSS syntax. You’ll have less need for nesting and CSS preprocessors (although those tools provide other benefits such as partials, loops, and minification).

:has() is considerably more revolutionary and exciting. Parent selection will rapidly become popular, and we’ll forget about the dark times! We’ll publish a full :has() tutorial when it’s available in all modern browsers.

If you’d like to dig in deeper to CSS pseudo-class selectors — along with all other things CSS, such as Grid and Flexbox — check out the awesome book CSS Master, by Tiffany Brown.