Selecting an Operating System

The fact that you’re reading this book means you want to learn about the Linux operating system (OS). To begin this journey, you must first understand what an OS is and what type of OS Linux is. This chapter is therefore devoted to these basic issues.

In this chapter, we describe what an OS is, how users interact with an OS, how Linux compares with other OSs with which you may be familiar, and how specific Linux implementations vary. Understanding these issues will help you find your way as you learn about Linux and switch between Linux-based and other systems.

- What is an OS?

- Investigating user interfaces

- Where does Linux fit in the OS world?

- What is a distribution?

What Is an OS?

An operating system, or OS, provides all of the most fundamental features of a computer, at least from a software point of view. An OS enables you to use the computer’s hardware devices, defines the user interface standards, and provides the basic tools that begin to make the computer useful. Ultimately, many of these features trace their way back to the OS’s kernel, which is described in more detail next. Other OS features are owed to additional programs that run atop the kernel, as described later in this chapter.

What Is a Kernel?

An OS kernel is a software component that’s responsible for managing various low-level features of the computer, including the following:

- Interfacing with hardware devices (network adapters, hard drives, and so on)

- Allocating memory to individual programs

- Allocating CPU time to individual programs

- Enabling programs to interact with each other

When you use a program (say, a web browser), it relies on the kernel for many of its basic functions. The web browser can communicate with the outside world only by using network functions provided by the kernel. The kernel allocates memory and CPU time to the web browser, without which it couldn’t run. The web browser may rely on plug-ins to display multimedia content; such programs are launched by and interact with the web browser through kernel services. Similar comments apply to any program that you run on a computer, although the details vary from one OS to another and from one program to another.

In sum, the kernel is the software “glue” that holds the computer together. Without a kernel, a modern computer can do very little.

Kernels are not interchangeable; the Linux kernel is different from the Mac OS X kernel or the Windows kernel. Each of these kernels uses a different internal design and provides different software interfaces for programs to use. Thus, each OS is built from the kernel up and uses its own set of programs that further define each OS’s features.

Many programs run on multiple kernels, but most need OS-specific tweaks. Programmers create binaries —the program files for a particular processor and kernel—for each OS.

Linux uses a kernel called Linux —in fact, technically speaking, the word Linux refers only to the kernel. Nonkernel programs provide other features that you might associate with Linux, most of which are available on other platforms, as described next in “What Else Identifies an OS.”

A student named Linus Torvalds created the Linux kernel in 1991. Linux has evolved considerably since that time. Today it runs on a wide variety of CPUs and other hardware. The easiest way to learn about Linux is to use it on a desktop or laptop PC, so that’s the type of configuration that’s emphasized in this book. The Linux kernel, however, runs on everything from tiny cell phones to powerful supercomputers.

What Else Identifies an OS?

The kernel is at the core of any OS, but it’s a component that most users don’t directly manipulate. Instead, most users interact with a number of other software components, many of which are closely associated with particular OSs. Such programs include the following:

![]()

Command-Line Shells Years ago, users interacted with computers exclusively by typing commands in a program (known as a shell) that accepted such commands. The commands would rename files, launch programs, and so on. Although many computer users today don’t use text-mode shells, they’re still important for intermediate and advanced Linux users, so we describe them in more detail in Chapter 6, “Getting to Know the Command Line,” and subsequent chapters rely heavily on your ability to use a text-mode shell. Many shells are available, and which shells are available and popular vary from one OS to another. In Linux, a shell known as the Bourne Again Shell (bash or Bash) is popular.

![]()

Graphical User Interfaces A graphical user interface (GUI) is an improvement on a text-mode shell, at least from the perspective of a beginning user. Instead of typing in commands, GUIs rely on icons, menus, and a mouse pointer. The Windows and Mac OS both have their own OS-specific GUIs. Linux relies on a GUI known as the X Window System, or X for short. X is a basic GUI, so Linux also uses desktop environment program suites, such as GNOME or the K Desktop Environment (KDE), to provide a more complete user experience. It’s the differences among Linux desktop environments and the GUIs in Windows or OS X that will probably strike you most when you first begin using Linux.

Utility Programs Modern OSs invariably ship with a wide variety of simple utility programs—calculators, calendars, text editors, disk maintenance tools, and so on. These programs differ from one OS to another. Indeed, even the names and methods of launching these programs can differ between OSs. Fortunately, you can usually find the programs you want by perusing menus in the main desktop environment.

You can search for Linux equivalents to popular OS X or Windows programs on websites such aswww .linuxrsp.ru/win-lin-soft/table-eng or www.linuxalt .com.

In addition to software that runs on an OS, several other features can distinguish between OSs, such as the details of user accounts, rules for naming disk files, and technical details of how the computer starts up. These features are all controlled by software that’s part of the OS, of course—sometimes by the kernel and sometimes by nonkernel software.

Libraries Unless you’re a programmer, you’re unlikely to need to work with libraries directly; nonetheless, we include them in this list because they provide critical services to programs. Libraries are collections of programming functions that can be used by a variety of programs. In Linux, for instance, most programs rely on a library called libc. Other libraries provide features associated with the GUI or that help programs parse options passed to them on the command line. Many libraries exist for Linux, which helps enrich the Linux software landscape.

Productivity Programs Major productivity programs—web browsers, word processors, graphics editors, and so on—are the usual reason for using a computer. Although such programs are often technically separate from the OS, they are sometimes associated with certain OSs. Even when a program is available on many OSs, it may have a different “feel” on each OS because of the different GUIs and other OS-specific features.

Investigating User Interfaces

Earlier, we noted the distinction between text-mode and graphical user interfaces. Although most end users favor GUIs because of their ease of use, Linux retains a strong text-mode tradition. Chapter 6 describes Linux’s text-mode tools in more detail, and Chapter 4, “Using Common Linux Programs,” covers basic principles of Linux GUI operations. It’s important that you have some grounding in the basic principles of both text-mode and graphical user interfaces now, since user interface issues crop up from time to time in intervening chapters.

Using a Text-Mode User Interface

In the past, and even sometimes today, Linux computers booted in text mode. Once the system had completely booted, the screen would display a simple text-mode login prompt, which might look like this:

![]()

Fedora release 21 (Twenty One)Kernel 3.18.6-200.fc21.x86_64 on an x86_64 (tty1)

essentials login:The details of such a login prompt vary from one system to another. This example includes several pieces of information:

- The OS name and version—Fedora Linux 21

- The computer’s name—

essentials - The name of the hardware device being used for the login—

tty1 - The login prompt itself—

login:

To log in to such a system, you must type your username at the login: prompt. The system then prompts you for a password, which you must also type. If you entered a valid username and password, the computer is likely to display a login message, followed by a shell prompt:

To try a text-mode login, you must first install Linux on a computer. Neither the Linux Essentials exam nor this book covers Linux installation. Consult your distribution’s documentation to learn more about installing Linux.

If you see a GUI login prompt, you can obtain a text-mode prompt by pressing Ctrl+Alt+F1 or Ctrl+Alt+F2. To return to the GUI login prompt, press Alt+F1 or Alt+F7.

[rich@essentials:~]$In this book, we omit most of the prompts from example commands when they appear on their own lines. We keep the dollar sign ($) prompt, though, for ordinary user commands. Some commands must be entered as root, which is the Linux administrative user. We change the prompt to a hash mark (#) for such commands, since most Linux distributions make a similar change to their prompts for the root user.

The details of this shell prompt vary from one installation to another, but you can type text-mode commands at the shell prompt. For instance, you could type ls (short for list) to see a list of files in the current directory. Removing vowels, and sometimes consonants, shortens the most basic commands, in order to minimize the amount of typing required to execute a command. This has the unfortunate effect of making many commands rather obscure.

Chapter 13, “Creating Users and Groups,” describes Linux accounts, including the root account, in more detail.

Some commands display no information, but most produce some type of output. For instance, the ls command produces a list of files:

$ ls106792c01.doc f0101.tifThis example shows two files in the current directory: 106792c01.doc and f0101.tif. You can use additional commands to manipulate these files, such as cp to copy them or rm to remove (delete) them. Chapter 6 and Chapter 7 (“Managing Files”) describe some common file-manipulation commands.

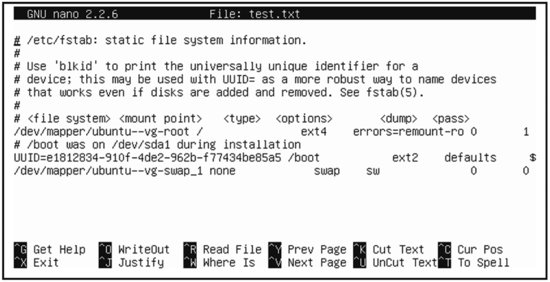

Some text-mode programs take over the display in order to provide constant updates or to enable you to interact with data in a flexible manner. Figure 1.1, for instance, shows the nano text editor, which is described in more detail in Chapter 10, “Editing Files.” Once nano is working, you can use your keyboard’s arrow keys to move the cursor around, add text by typing, and so on.

Figure 1.1 Some text-mode programs take over the entire display.

Even if you use a graphical login, you can use a text-mode shell inside a window, known as a terminal. Common Linux GUIs provide the ability to launch a terminal program, which delivers a shell prompt and the means to run text-mode programs.

Using a Graphical User Interface

![]()

Most users are more comfortable with GUIs than with text-mode commands. Thus many modern Linux systems start up in GUI mode by default, presenting a login screen similar to the one shown in Figure 1.2. You can select your username from a list or type it, followed by typing your password, to log in.

Figure 1.2 Graphical login screens on Linux are similar to those for Windows or OS X.

Unlike Windows and OS X, Linux provides a number of desktop environments. Which one you use depends on the specific variety of Linux you’re using, what software options you selected at installation time, and your own personal preferences. Common choices include GNOME, KDE, Xfce, and Unity. Many other options are available as well. Many graphical desktops have assistive technology features built in. In Figure 1.2, the person icon in the top-right corner of the Ubuntu login window lets you select an assistive technology, such as a screen reader or onscreen keyboard, to assist you with the login entry.

Some Linux GUI login screens don’t prompt you for a password until after you’ve entered a valid username.

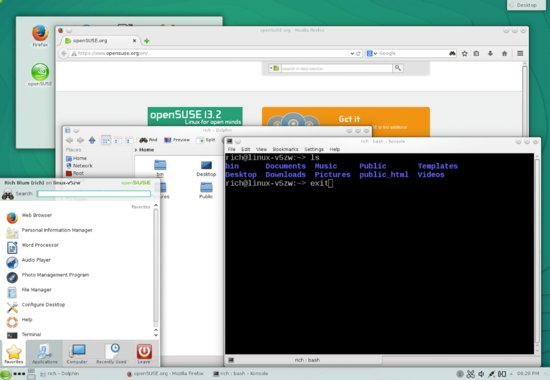

Linux desktop environments can look quite different from one another, but they all provide similar functionality. Figure 1.3 shows the default KDE on an openSUSE 13.2 installation with a couple of programs running.

Figure 1.3 Linux desktop environments provide the types of GUI controls that most users expect.

Chapter 4 describes common desktop environments and their features in more detail, but for now you should know that they all provide features such as these:

Program Launchers You can launch programs by selecting them from menus or lists. Typically, one or more menus exist along the top, bottom, or side of the screen. In Figure 1.3, you can click the openSUSE gecko icon in the bottom-left corner of the screen to produce the menu that appears in that figure.

File Managers Linux provides GUI file managers similar to those in Windows or OS X. A window for one of these is open in the center of Figure 1.3.

Window Controls You can move windows by clicking and dragging their title bars, resize them by clicking and dragging their edges, and so on.

Multiple Desktops Most Linux desktop environments enable you to keep multiple virtual desktops active, each with their own set of programs. This feature is handy to keep the screen uncluttered while you run many programs simultaneously. Typically, an icon in one of the menus enables you to switch between virtual desktops.

Logout Options You can log out of your Linux session, which enables you to shut down the computer or let another user log in.

Logging out is important in public computing environments. If you fail to log out, a stranger might come along and use your account for malicious purposes.

As you learn more about Linux, you’ll discover that its GUI environments are quite flexible. If you find that you don’t like the default environment for your distribution, you can change it. Although they all provide similar features, some people have strong preferences about desktop environments. Linux gives you a choice in the matter that is not available in Windows or OS X, so feel free to try multiple desktop environments.

You may need to install extra desktop environments to use them. This topic is not covered in this book.

Where Does Linux Fit in the OS World?

As described later, in “What Is a Distribution?,” Linux can be considered a family of OSs. Thus you can compare one Linux version to another one.

This chapter’s title implies a comparison, and as this book is about Linux, the comparison must be with non-Linux OSs. Thus we compare Linux to three other OSs or OS families: Unix, Mac OS X, and Microsoft Windows.

Comparing Linux to Unix

![]()

If you were to attempt to draw a “family tree” of OSs, you would end up scratching your head a lot. This is because OS designers often mimic each other’s features, and sometimes even incorporate each other’s ideas into their OSs’ workings. The result can be a tangled mess of similarities between OSs, with causes ranging from coincidence to code “borrowing.” Attempting to map these influences can be difficult. In the case of Linux and Unix, though, a broad statement is possible: Linux is modeled after Unix.

Unix was created in 1969 at AT&T’s Bell Labs. Unix’s history is complex and involves multiple forks (that is, splitting of the code into two or more independent projects) and even entirely separate code rewrites. Modern Linux systems are, by and large, the product of open source projects that clone Unix programs, or of original open source code projects for Unix generally. These projects include the following:

You can not only run open source software, but also modify and redistribute it yourself. Chapter 3, “Investigating Linux’s Principles and Philosophy,” covers the philosophy and legal issues concerning open source software.

The Linux Kernel Linus Torvalds created the Linux kernel as a hobby programming project in 1991, but it soon grew to be much more than that. The Linux kernel was designed to be compatible with other Unix kernels, in the sense that it used the same software interfaces in source code. This made using open source programs for other Unix versions with the Linux kernel easy.

The GNU Project The GNU’s Not Unix (GNU) project is an effort by the Free Software Foundation (FSF) to develop open source replacements for all of the core elements of a Unix OS. In 1991, the FSF had already released the most important of such tools, with the notable exception of the kernel. (The GNU HURD kernel is now available, but is not as popular as the Linux kernel.) Alternatives to the GNU tools include proprietary commercial tools and open source tools developed for the Berkeley Software Distribution (BSD) Unix variants. The tools used on a Unix-like OS can influence its overall “flavor,” but all of these tool sets are similar enough to give any Unix variety a similar feel when compared to a non-Unix OS.

GNU is an example of a recursive acronym—an acronym whose expansion includes the acronym itself. This is an example of geek humor.

Xorg-X11 The X Window System is the GUI environment for most Unix OSs. Most Linux distributions today use the Xorg-X11 variety of X. As with the basic text-mode tools provided by the GNU project, choice of an X server can affect some features of a Unix-like OS, such as the types of fonts it supports.

Desktop Environments GNOME, KDE, Unity, Xfce, and other popular open source desktop environments have largely displaced commercial desktop environments, even on commercial versions of Unix. Thus you won’t find big differences between Linux and Unix in this area.

Mac OS X, described shortly, is a commercial Unix-based OS that eschews both X and the desktop environments that run on it in favor of Apple’s own GUI.

Server Programs Historically, Unix and Linux have been popular as server OSs—organizations use them to run web servers, email servers, file servers, and so on. Linux runs the same popular server programs as do commercial Unix versions and the open source BSDs.

User Productivity Programs In this realm, as in server programs, Linux runs the same software as do other Unix-like OSs. In a few cases, Linux runs more programs, or runs them better. This is mostly because of Linux’s popularity and the vast array of hardware drivers that Linux offers. If a program needs advanced video card support, for example, it’s more likely to find that support on Linux than on a less popular Unix-like OS.

On the whole, Linux can be thought of as a member of the family of Unix-like OSs. Although Linux is technically not a Unix OS, it’s similar enough that the differences are unimportant compared to the differences between this family as a whole and other OSs, such as Windows. Because of its popularity, Linux offers better hardware support, at least on commodity PC hardware. Some Unix varieties offer specific features that Linux lacks, though. For instance, the Zettabyte File System (ZFS), available on Solaris, FreeBSD, and some other OSs, provides advanced filesystem features that aren’t yet fully implemented in Linux.

A ZFS add-on for Linux is available, but it’s not fully integrated into the OS. A Linux filesystem known as Btrfs offers many ZFS features, and it is gaining in popularity among various Linux distributions.

Comparing Linux to Mac OS X

![]()

Mac OS X is a commercial Unix-based OS that borrows heavily from the BSDs and discards the usual Unix GUI (namely X) in favor of its own user interface. This makes OS X both very similar to Linux and quite different from it.

Code Types

Programmers write programs in a form known as source code. Although source code can seem arcane to the uninitiated, it’s crystal clear compared to the form a program must take for a computer to run it—that is, binary code. A program known as a compiler translates source code to binary code. (Alternatively, some programming languages rely on an interpreter, which converts source code to binary code “on the fly,” eliminating the need to compile source code.)

The term open source refers to the availability of source code. This is generally withheld from the public in the case of commercial software programs and OSs. Conversely, a programmer with access to a program’s source code through open source software can fix bugs, add features, and otherwise alter how the program operates.

You can open an OS X Terminal window and type many of the same commands described in this book to achieve similar ends. If a command described in this book isn’t present, you may be able to install it in one way or another. OS X ships with some popular Unix server programs, so you can configure it to work much like Linux or another Unix-like OS as a network server computer.

OS X differs from Linux in its user interface, though. The OS X user interface is known as Cocoa from a programming perspective, or Aqua from a user’s point of view. It includes elements that are roughly equivalent to both X and a desktop environment in Linux. Because Cocoa isn’t compatible with X from a programming perspective, applications developed for OS X can’t be run directly on Linux (or on other Unix-like OSs), and porting them (that is, modifying the source code and recompiling them) for Linux is a nontrivial undertaking. Thus native OS X applications seldom make the transition to Linux.

The X in X server is a letter X, but the X in OS X is a Roman numeral (10), denoting the tenth version of Mac OS.

OS X includes an implementation of X that runs under Aqua. This makes the transfer of GUI Linux and Unix programs to OS X relatively straightforward. The resulting programs don’t entirely conform to the Aqua user interface, though. They may have buttons, menus, and other features that look out of place compared to the usual appearance of OS X equivalents.

Apple makes OS X available for its own computers. Its license terms forbid installation on non-Apple hardware and, putting aside licensing issues, installing OS X on non-Apple hardware is a nontrivial undertaking. A variant of OS X, known as iOS, runs on Apple’s iPad and iPhone devices, and it is equally nonportable to other devices. Thus OS X is largely limited to Apple hardware. Linux, by contrast, runs on a wide variety of hardware, including most PCs. You can even install Linux on Macintosh computers.

Comparing Linux to Windows

![]()

Most desktop and laptop computers today run Microsoft Windows. Thus if you’re considering running Linux, the most likely comparison is to Windows. Broadly speaking, Linux and Windows have similar capabilities; however, there are significant differences in details. These include the following:

Licensing Linux is an open source OS, whereas Windows is a proprietary commercial OS. Chapter 2, “Understanding Software Licensing,” covers open source issues in greater detail, but for now you should know that open source software gives you greater control over your computer than does proprietary software—at least in theory. In practice, you may need a great deal of expertise to take advantage of open source’s benefits. Proprietary software may be preferable if you work for an organization that’s comfortable only with the idea of software that’s sold in a more traditional way. (Some Linux variants, though, are sold in a similar way, along with service contracts.)

Costs Many Linux varieties are available free of charge, and so they are appealing if you’re trying to cut costs. On the other hand, the expertise needed to install and maintain a Linux installation is likely to be greater, and therefore more expensive than the expertise needed to install and maintain a Windows installation. Different studies on the issue of total cost of ownership of Linux vs. Windows have gone both ways, but most tend to favor Linux.

Hardware Compatibility Most hardware components require OS support, usually in the form of drivers. Most hardware manufacturers provide Windows drivers for their devices, or they work with Microsoft to ensure that Windows includes appropriate drivers. Although some manufacturers provide Linux drivers, too, for the most part the Linux community as a whole must supply the necessary drivers. This means that Linux drivers may take a few weeks or even months to appear after a device becomes available. On the other hand, Linux developers tend to maintain drivers for old hardware for much longer than manufacturers continue to support their own old hardware. Thus a modern Linux may run better than a recent version of Windows on old hardware. Linux also tends to be less resource-intensive, so you can be productive on older hardware when using Linux.

Software Availability Some popular desktop applications, such as Microsoft Office, are available on Windows but not on Linux. Although Linux alternatives, such as Apache OpenOffice.org or LibreOffice, are available, they haven’t caught on in the public’s mind. In other realms, the situation is reversed. Popular server programs, such as the Apache web server, were developed first for Linux or Unix. Although many such servers are available for Windows, they run more efficiently on Linux. If you have a specific program that you must run, you may want to research its availability and practicality on any of the platforms that you’re considering.

User Interfaces Like OS X, Windows uses its own unique user interface. This fact contributes to poor inter-OS portability. (Tools exist to help bridge the gap, though; X Window System implementations for Windows are available, as are tools for running Windows programs in Linux.) Some users prefer the Windows user interface to any Linux desktop environment, but others prefer a Linux desktop environment.

Microsoft has made major changes to its user interface, starting with Windows 8. The updated user interface, called Metro, works in a similar manner on everything from smartphones to desktop computers.

Configurability Linux is much more configurable OS than Windows. Although both OSs provide the means to run specific programs at startup, change user interface themes, and so on, Linux’s open source nature means that you can tweak any detail that you wish. Furthermore, you can pick any Linux variant that you like to get a head start on setting up the system as you see fit.

Security Advocates of each OS claim it’s more secure than the other. They can do this because they focus on different security issues. Many of the threats to Windows come from viruses, which by and large target Windows and its huge installed user base. Viruses are essentially a nonissue for Linux; in Linux, security threats come mostly from break-ins involving misconfigured servers or untrustworthy local users.

For over two decades, Windows has dominated the desktop arena. In both homes and offices, users have become familiar with Windows and are used to popular Windows applications, such as Microsoft Office. Although Linux can be used in such environments, it’s a less popular choice for a variety of reasons—its unfamiliarity, the fact that Windows comes preinstalled on most PCs, and the lack of any compelling Linux-only applications for most users.

Unix generally, and Linux in particular, on the other hand, have come to dominate the server market. Linux powers the web servers, email servers, file servers, and so on that make up the Internet and that many businesses rely on to provide local network services. Thus most people use Linux daily even if they don’t realize it.

In most cases, it’s possible to use either Linux or Windows on a computer and have it do an acceptable job. Sometimes, though, specific needs dictate the use of one OS or another. You might need to run a particular exotic program, for instance, or your hardware might be too old for modern Windows or too new for Linux. In other cases, your own or your users’ familiarity with one OS or the other may favor its use.

What Is a Distribution?

Up until now, we’ve described Linux as if it were a single OS, but this isn’t really the case. Many different Linux distributions are available, each consisting of a Linux kernel along with a set of utilities and configuration files. The result is a complete OS, and two Linux distributions can differ from each other as much as either differs from OS X or Windows. We therefore describe in more detail what makes up a distribution, what distributions are popular, and the ways in which distribution maintainers keep their offerings up-to-date.

Creating a Complete Linux-Based OS

![]()

We’ve already described some of what makes up a Linux OS, but some details need reiteration or elaboration:

A Linux Kernel A Linux kernel is at the core of any Linux OS, of course. We’ve written this item as a Linux kernel because the Linux kernel is constantly evolving. Two distributions are likely to use slightly different kernels. Distribution maintainers also offer patch kernels—that is, they make small changes to fix bugs or add features.

Core Unix Tools Tools such as the GNU tool set, the X Window System, and the utilities used to manage disks are critical to the normal functioning of a Linux system. Most Linux distributions include more or less the same set of such tools, but as with the kernel, they can vary in versions and patches.

Supplemental Software Additional software, such as major server programs, desktop environments, and productivity tools, ship with most Linux distributions. As with core Unix software, most Linux distributions provide similar options for such software. Distributions sometimes provide their own “branding,” though, particularly in desktop environment graphics.

Startup Scripts Much of a Linux distribution’s “personality” comes from the way it manages its startup process. Linux uses scripts and utilities to launch the dozens of programs that link the computer to a network, present a login prompt, and so on. These scripts and utilities vary between distributions, which means that they have different features and may be configured in different ways.

An Installer In order to be used, software must be installed, and most Linux distributions provide unique installation software to help you manage this important task. Thus two distributions may install in different ways, giving you different options for key features, such as disk layouts and initial user account creation.

Typically, Linux distributions are available for download from their websites. You can usually download a CD-R or DVD image file that you can then burn to an optical disc. When you boot the resulting disc, the installer runs, and you can install the OS. You can sometimes download an image that can be copied to a USB flash drive if your computer lacks an optical drive. There are also cloud versions of many Linux distributions, which allow you to download a complete Linux system to run in either a private virtual machine or on a commercial cloud such as Amazon or Google cloud services.

The UNetbootin tool (http:// unetbootin .sourceforge .net) can copy the files from a Linux installation disc image file to a USB flash drive.

Some Linux installers come complete with all of the software you’re likely to install. Others come with only minimal software and expect you to have a working Internet connection so that the installer can download additional software. If your computer isn’t connected to the Internet, be sure to get the right type of installer.

Exploring Common Linux Distributions

![]()

Depending on how you count, there are about a dozen major Linux distributions for desktop, laptop, and small server computers, and hundreds more that serve specialized purposes. Table 1.1 summarizes the features of the most important distributions.

Table 1.1 Features of major Linux distributions

| Distribution | Availability | Package format | Release cycle | Administrator skill requirements |

| Arch | Free | pacman | Rolling | Expert |

| CentOS | Free | RPM | Approximately 2-year | Intermediate |

| Debian | Free | Debian | 2-year | Intermediate to expert |

| Fedora | Free | RPM | Approximately 6-month | Intermediate |

| Gentoo | Free | ebuild | Rolling | Expert |

| Mint | Free | Debian | 6-month | Novice to intermediate |

| openSUSE | Free | RPM | 8-month | Intermediate |

| Red Hat Enterprise | Commercial | RPM | Approximately 2-year | Intermediate |

| Scientific | Free | RPM | Approximately 6-month | Intermediate to expert |

| Slackware | Free | tarballs | Irregular | Expert |

| SUSE Enterprise | Commercial | RPM | 2–3 years | Intermediate |

| Ubuntu | Free | Debian | 6-month | Novice to intermediate |

These features require explanation:

Availability Most Linux distributions are entirely open source or free software; however, some include proprietary components and are for sale only, typically with a support contract. Red Hat Enterprise Linux (RHEL) and SUSE Enterprise Linux are the two most prominent examples of this type of distribution. Both have completely free cousins. For RHEL, CentOS is a near-clone that omits the proprietary components, and Fedora is an open source version that serves as a testbed for technologies that may eventually be included in RHEL. For SUSE Enterprise, openSUSE is a free alternative.

Package Format Most Linux distributions distribute software in packages, which are collections of many files in one. Package software maintains a local database of installed files, making upgrades and uninstallations easy. The RPM Package Manager (RPM) system is the most popular one in the Linux world, but Debian packages are common, too. Other packaging systems work fine, but they are distribution-specific. Slackware is unusual in that it uses tarballs for its packages. These are package files created by the standard tar utility, which is used for backing up computers and for distributing source code, among other things. The tarballs that Slackware uses for its packages contain Slackware-specific information to help with package management. Gentoo is unusual because its package system is based on compiling most software from source code. This is time-consuming, but it enables experienced administrators to tweak compilation options to optimize the packages for their own hardware and software environments.

Tarballs are similar to the zip files that are common on Windows. Chapter 8, “Searching, Extracting, and Archiving Data,” describes how to create and use tarballs.

Release Cycle We describe release cycles in more detail shortly, in “Understanding Release Cycles.” As a general rule, distributions with short release cycles aim to provide the latest software possible, whereas those with longer release cycles strive to provide the most stable environments possible. Some try to have it both ways; for instance, Ubuntu releases long-term support (LTS) versions in April of even-numbered years. Its other releases aim to provide the latest software.

Administrator Skill Requirements The final column in Table 1.1 provides our personal estimation of the skill level required to administer a distribution. As you can see, we’ve described most Linux distributions as requiring “intermediate” skill to administer. Some, however, provide less in the way of user-friendly GUI administrative tools, and so require more skill. Ubuntu aims to be particularly easy to use and administer.

Don’t be scared off by the “intermediate” classification of most distributions. This book’s purpose is to help you manage the essential features of such distributions.

Most Linux distributions are available for at least two platforms—that is, CPU types: x 86 (also known as IA32, i386, and several variants) and x 86-64 (also known as AMD64, EM64T, and x 64). Until about 2007, x 86 computers were the most common variety, but now x 86-64 computers have become the standard. If you have an x 86-64 computer, you can run either an x 86 or an x 86-64 distribution on it, although the latter provides a small speed improvement. More-exotic platforms, such as ARM (for tablets), PowerPC, Alpha, and SPARC, are available. Such platforms are mostly restricted to servers and to specialized devices (described shortly).

In addition to the mainstream PC distributions, several others are available that serve more specialized purposes. Some of these run on regular PCs, but others run on their own specialized hardware:

Android Many cell phones today use a Linux-based OS known as Android. Its user interface is similar to that of other smartphones, but underneath lies a Linux kernel and a significant amount of the same Linux infrastructure that you’ll find on a PC. Such phones don’t use X or typical desktop applications, though; instead, they run specialized applications for mobile phones.

Android is best known as a mobile phone OS, but it can be used on other devices. Some tablets and e-book readers, for instance, run Android.

Network Appliances Many broadband routers, print servers, and other devices that you plug into a local network to perform specialized tasks run Linux. You can sometimes replace the standard OS with a customized one if you want to add features to the device. Tomato (www.polarcloud.com/tomato) and OpenWrt (https://openwrt.org) are two examples of such customized Linux distributions. Don’t install such software on a whim, though; if done improperly, or on the wrong device, they can render the device useless!

TiVo This popular digital video recorder (DVR) uses a Linux kernel and a significant number of standard support programs, along with proprietary drivers and DVR software. Although many people who use them don’t realize it, they are Linux-based computers under the surface.

Parted Magic This distribution, based at http://partedmagic.com, is a Linux distribution for PCs that’s intended for emergency recovery operations. It runs from a single CD-R, and you can use it to access a Linux or Windows hard drive if the main installation won’t boot.

We recommend that you download Parted Magic, or a similar tool, to have on hand in case you run into problems with your main Linux installation.

![]()

Android, Linux-based network appliances, and TiVo are examples of embedded systems that use Linux. Such devices typically require little or no administrative work from users, at least not in the way that such tasks are described in this book. Instead, these devices have fixed basic configurations and guided setup tools to help inexperienced users set critical basic options, such as network settings and time zones.

Understanding Release Cycles

![]()

Table 1.1 summarized the release cycles employed by a number of common Linux distributions. The values cited in that table are the time between releases. For instance, new versions of Ubuntu come out every six months, like clockwork. Most other distributions’ release schedules provide some “wiggle room”; if a release date slides a month, that may be acceptable.

After its release, a distribution is typically supported until sometime after the next version’s release—typically a few months to a year or more. During this support period, the distribution’s maintainers provide software updates to fix bugs and security problems. Once the support period has passed, you can continue to use a distribution, but you’re on your own—if you need updated software, you’ll have to compile it from source code yourself or hope that you can find a compatible binary package from another source. As a practical matter, therefore, it’s generally a good idea to upgrade to the latest version before the support period ends. This fact makes distributions with longer release cycles appealing to businesses, since a longer time between installations minimizes disruptions and costs associated with upgrades.

Two of the distributions in Table 1.1 (Arch and Gentoo) have rolling release cycles. Such distributions have no version numbers in the usual sense; instead, upgrades occur in an ongoing manner. Using such a distribution makes it unnecessary ever to do a full upgrade, with all of the hassles that entails; however, you’ll occasionally have to do a disruptive upgrade of one particular subsystem, such as a major upgrade in your desktop environment.

![]()

Prior to the release of a new version, most distributions make prerelease versions available. Alpha software is extremely new and very likely to contain serious bugs, while beta software is more stable but nonetheless more likely to contain bugs than the final-release software. As a general rule, you should avoid using such software unless you want to contribute to the development effort by reporting bugs or unless you’re desperate to have a new feature.

The Essentials and Beyond

Linux is a powerful OS that you can use on everything from a smartphone to a supercomputer. At Linux’s core is its kernel, which manages the computer’s hardware. Built atop that are various utilities (many from the GNU project) and user applications. Linux is a clone of the Unix OS, with which it shares many programs. Mac OS X is another Unix OS, although one with a unique user interface. Although Windows shares many features with Unix, it’s an entirely different OS, so software compatibility between Linux and Windows is limited.

Linux comes in many varieties, known as distributions, each of which has its own unique “flavor.” Because of this variety, you can pick a Linux version that best suits your needs, based on its ease of use, release cycle, and other unique features.

Suggested Exercises

- Make a list of the programs that you run as an ordinary user, including everything from a calculator applet to a major office suite. Look for equivalents at www.linuxrsp.ru/win-lin-soft/table-eng or www.linuxalt.com. Is there anything that you can’t find? If so, try a web search to find an equivalent.

- Read more about two or three Linux distributions by perusing their web pages. Which distribution would you select for running a major web server? Which distribution sounds most appealing for use by office workers who use word processing and email?

Review Questions

- Which of the following is not a function of the Linux kernel?

- Allocating memory for use by programs

- Allocating CPU time for use by programs

- Creating menus in GUI programs

- Controlling access to the hard drive

- Enabling programs to use a network

- Which of the following is an example of an embedded Linux OS?

- Android

- SUSE

- CentOS

- Debian

- Fedora

- Which of the following is a notable difference between Linux and Mac OS X?

- Linux can run common GNU programs, whereas OS X cannot.

- Linux’s GUI is based on the X Window System, whereas OS X’s is not.

- Linux cannot run on Apple Macintosh hardware, whereas OS X can run only on Apple hardware.

- Linux relies heavily on BSD software, whereas OS X uses no BSD software.

- Linux supports text-mode commands, but OS X is a GUI-only OS.

- True or false: The Linux kernel is derived from the BSD kernel.

- True or false: If you log in to a Linux system in graphical mode, you cannot use text-mode commands in that session.

- True or false: CentOS is a Linux distribution with a long release cycle.

- A Linux text-mode login prompt reads ___________ (one word).

- A common security problem with Windows that’s essentially nonexistent on Linux is ___________.

- Prerelease software that’s likely to contain bugs is known as ___________ and ___________.

- Linux distributions that have no version number but instead release upgrades in an ongoing manner are said to have a(n) ___________ release cycle.