An Introduction to the :has() Selector in CSS

In this excerpt from Unleashing the Power of CSS, we take a deep dive into how to select elements with the CSS :has() selector.

Heralded as “the parent selector”, the :has() pseudo-class has far greater range than just styling an element’s ancestor. With its availability in Safari 15.4+ and Chromium 105+, and behind a flag in Firefox, it’s a great time for you to become familiar with :has() and its use cases.

As a pseudo-class, the basic functionality of :has() is to style the element it’s attached to — otherwise known as the “target” element. This is similar to other pseudo-classes like :hover or :active, where a:hover is intended to style the <a> element in an active state.

However, :has() is also similar to :is(), :where(), and :not(), in that it accepts a a list of relative selectors within its parentheses. This allows :has() to create complex criteria to test against, making it a very powerful selector.

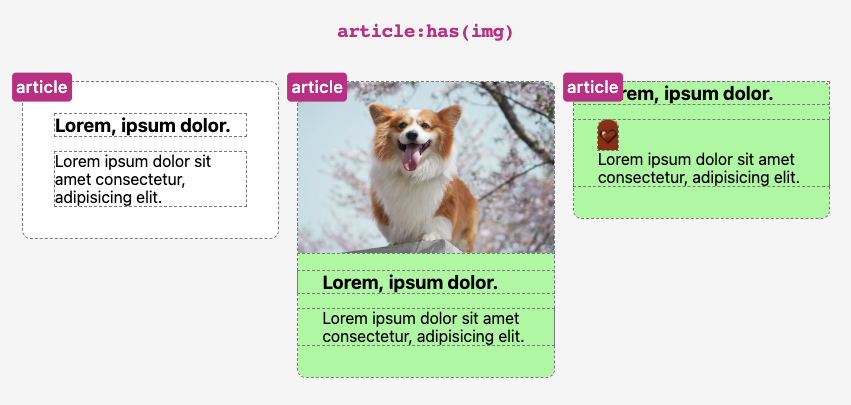

To get a feel for how :has() works, let’s look at an example of how to apply it. In the following selector, we’re testing if an <article> element has an <img> element as a child:

article:has(img) {}

A possible result of this selector is shown in the image below. Three article elements are shown, two containing images and both having a palegreen background and different padding from the one without an image.

The selector above will apply as long as an <img> element exists anywhere with the <article> element — whether as a direct child or as a descendant of other nested elements.

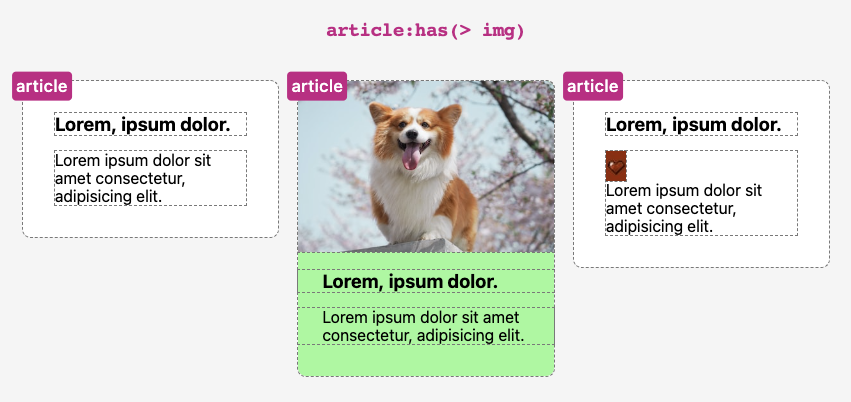

If we want to make sure the rule applies only if the <img> is a direct (un-nested) child of the <article> element, we can also include the child combinator:

article:has(> img) {}

The result of this change is shown in the image below. The same three cards are shown, but this time only the one where the image is a direct child of the <article> has the palegreen background and padding.

In both selectors, the styles we define are applied to the target element, which is the <article>. This is why folks often call :has() the “parent” selector: if certain elements exist in a certain way, their “parent” receives the assigned styles.

Note: the :has() pseudo-class itself doesn’t add any specificity weight to the selector. Like :is() and :not(), the specificity of :has() is equal to the highest specificity selector in the selector list. For example, :has(#id, p, .class) will have the specificity afforded to an id. For a refresher on specificity, review the section on specificity in CSS Master, 3rd Edition.

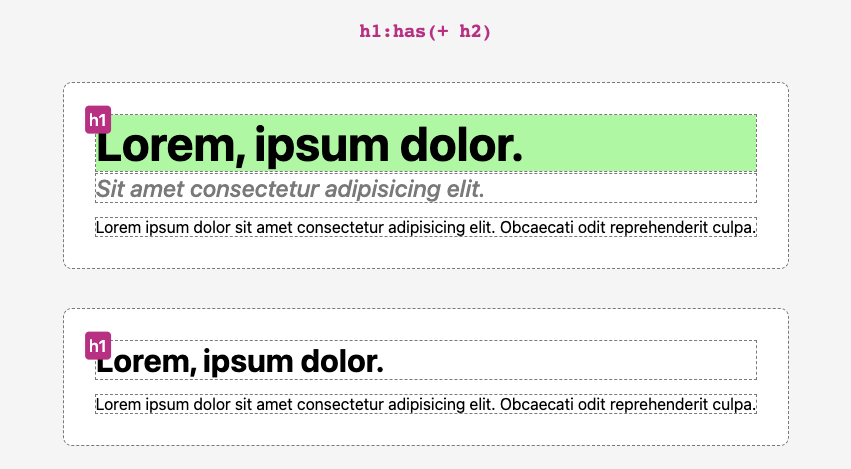

We can also select a target element if it’s followed by a specific sibling element using the adjacent sibling combinator (+). In the following example, we’re selecting an <h1> element only if it’s directly followed by an <h2>:

h1:has(+ h2) {}

In the image below, two <article> elements are shown. In the first one, because the <h1> is followed by an <h2>, the <h1> has a palegreen background applied to it.

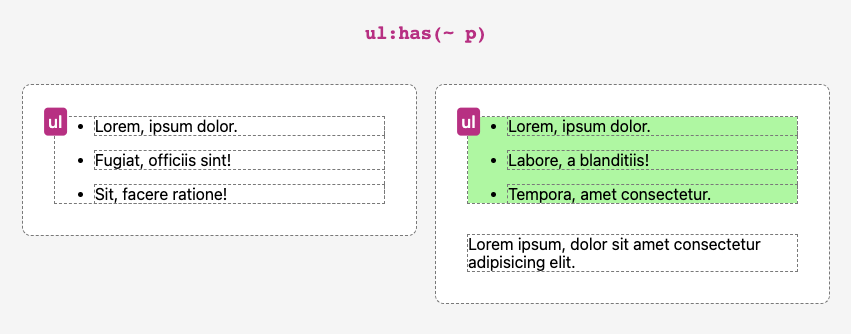

Using the general sibling combinator (~), we can check if a specific element is a sibling anywhere following the target. Here, we’re checking if there’s a <p> element somewhere as a sibling of the <ul>:

ul:has(~ p) {}

The image below shows two <article> elements, each containing an unordered list. The second article’s list is followed by a paragraph, so it has a palegreen background applied.

The selectors we’ve used so far have styled the target element attached to :has(), such as the <ul> in ul:has(~ p). Just as with regular selectors, our :has() selectors can be extended to be far more complex, such as setting styling conditions for elements not directly attached to the :has() selector.

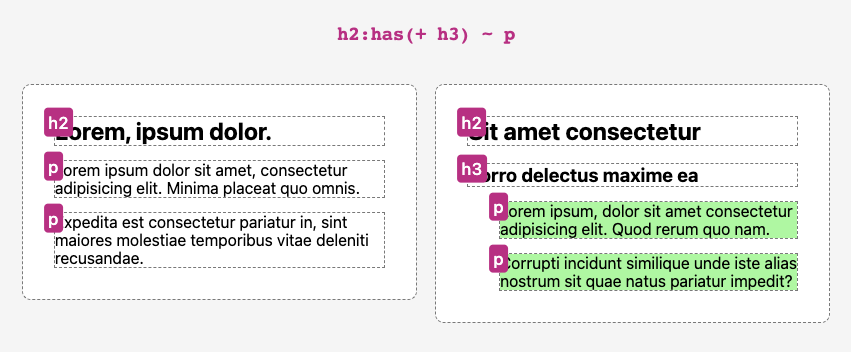

In the following selector, the styles apply to any <p> elements that are siblings of an <h2> that itself has an <h3> as an adjacent sibling:

h2:has(+ h3) ~ p

In the image below, two <article> elements are shown. In the second, the paragraphs are styled with a palegreen background and an increased left margin, because the paragraphs are siblings of an <h2> followed by an <h3>.

Note: we’ll be more successful using :has() if we have a good understanding of the available CSS selectors. MDN offers a concise overview of selectors, and I’ve written a two-part series on selectors with additional practical examples.

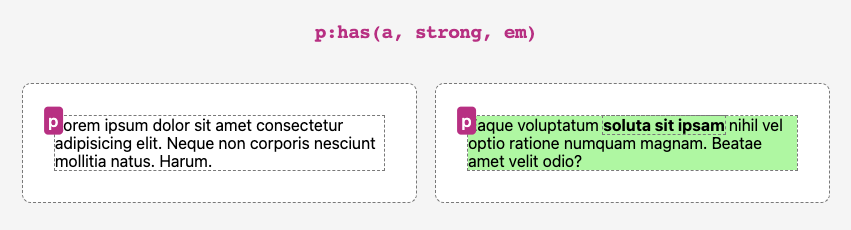

Remember, :has() can accept a list of selectors, which we can think of as OR conditions. Let’s select a paragraph if it includes <a> _or_ <strong> _or_ <em>:

p:has(a, strong, em) {}

In the image below, there are two paragraphs. Because the second paragraph contains a <strong> element, it has a palegreen background.

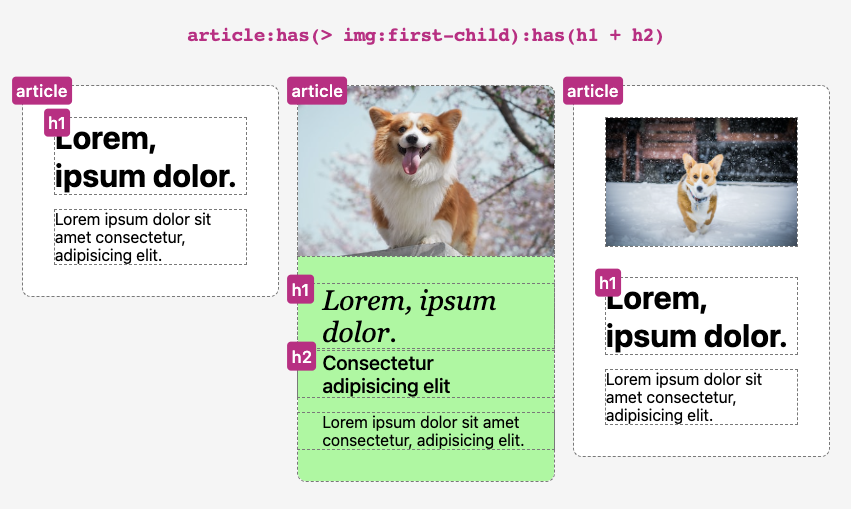

We can also chain :has() selectors to create AND conditions. In the following compound selector, we’re testing both that an <img> is the first child of the <article>, and that the <article> contains an <h1> followed by an <h2>:

article:has(> img:first-child):has(h1 + h2) {}

The image below shows three <article> elements. The second article has a palegreen background (along with other styling) because it contains both an image as a first child and an <h1> followed by an <h2>.

You can review all of these basic selector examples in the following CodePen demo.

See the Pen

:has() selector syntax examples by SitePoint (@SitePoint)

on CodePen.

This article is excerpted from Unleashing the Power of CSS: Advanced Techniques for Responsive User Interfaces, available on SitePoint Premium.