An Introduction to Native CSS Nesting

Nesting is one of the core reasons for using a CSS preprocessor such as Sass. The feature has now arrived in standard browser CSS with a similar syntax. Can you drop the preprocessor dependency from your build system?

CSS nesting saves typing time and can make the syntax easier to read and maintain. Up till now, you’ve had to type full selector paths like this:

.parent1 .child1,

.parent2 .child1 {

color: red;

}

.parent1 .child2,

.parent2 .child2 {

color: green;

}

.parent1 .child2:hover,

.parent2 .child2:hover {

color: blue;

}

Now, you can nest child selectors inside their parent, like so:

.parent1, .parent2 {

.child1 {

color: red;

}

.child2 {

color: green;

&:hover {

color: blue;

}

}

}

You can nest selectors as deep as you like, but be wary about going beyond two or three levels. There’s no technical limit to the nesting depth, but it can make code harder to read and the resulting CSS may become unnecessarily verbose.

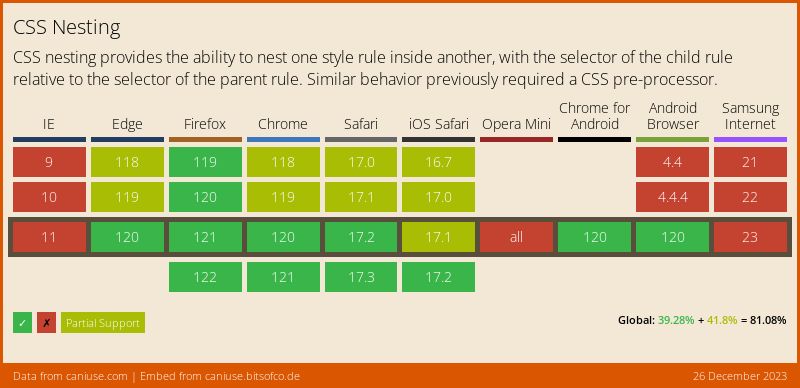

Until April 2023, no browser understood the nested CSS syntax. You required a build step with a CSS preprocessor such as Sass, Less, or PostCSS to transform the nested code to the regular full-selector syntax. Nesting has now arrived in Chrome 112+ and Safari 16.5+, with Firefox support coming later in 2023 (version 115 has it available behind a feature flag).

Can you drop your preprocessor in favor of native nesting? As usual … it depends. Native nesting syntax has evolved over the past couple of years. It’s superficially similar to Sass — which will please most web developers — but don’t expect all SCSS code to work directly as you expect.

Native CSS Nesting Rules

You can nest any selector inside another, but it must start with a symbol such as &, . (for a HTML class), # (for a HTML id), @ (for a media query), :, ::, *, +, ~, >, or [. In other words, it cannot be a direct reference to an HTML element. This code is invalid and the <p> selector is not parsed:

.parent1 {

/* FAILS */

p {

color: blue;

}

}

The easiest way to fix this is to use an ampersand (&), which references the current selector in an identical way to Sass:

.parent1 {

/* WORKS */

& p {

color: blue;

}

}

Alternatively, you could use one of these:

-

> p— but this would style direct children of.parent1only -

:is(p)— but :is() uses the specificity of the most specific selector -

:where(p)— but :where() has zero specificity

They would all work in this simple example, but you could encounter specificity issues later with more complex stylesheets.

The & also allows you to target pseudo-elements and pseudo-classes on the parent selector. For example:

p.my-element {

&::after {}

&:hover {}

&:target {}

}

If you don’t use &, you’ll be targeting all child elements of the selector and not p.my-element itself. (The same would occur in Sass.)

Note that you can use an & anywhere in the selector. For example:

.child1 {

.parent3 & {

color: red;

}

}

This translates to the following non-nested syntax:

.parent3 .child1 { color: red; }

You can even use multiple & symbols in a selector:

ul {

& li & {

color: blue;

}

}

This would target nested <ul> elements (ul li ul), but I’d recommend against using this if you want to keep your sanity!

Finally, you can nest media queries. The following code applies a cyan color to paragraph elements — unless the browser width is at least 800px, when they become purple:

p {

color: cyan;

@media (min-width: 800px) {

color: purple;

}

}

Native CSS Nesting Gotchas

Native nesting wraps parent selectors in :is(), and this can lead to differences with Sass output.

Consider the following nested code:

.parent1, #parent2 {

.child1 {}

}

This effectively becomes the following when it’s parsed in a browser:

:is(.parent1, #parent2) .child1 {}

A .child1 element inside .parent1 has a specificity of 101, because :is() uses the specificity of its most specific selector — in this case, the #parent2 ID.

Sass compiles the same code to this:

.parent1 .child1,

#parent2 .child1 {

}

In this case, a .child1 element inside .parent1 has a specificity of 002, because it matches the two classes (#parent2 is ignored). Its selector is less specific than the native option and has a greater chance of being overridden in the cascade.

You may also encounter a subtler issue. Consider this:

.parent .child {

.grandparent & {}

}

The native CSS equivalent is:

.grandparent :is(.parent .child) {}

This matches the following mis-ordered HTML elements:

<div class="parent">

<div class="grandparent">

<div class="child">MATCH</div>

</div>

</div>

MATCH becomes styled because the CSS parser does the following:

-

It finds all elements with a class of

childwhich also have an ancestor ofparent— at any point up the DOM hierarchy. -

Having found the element containing

MATCH, the parser checks whether it has an ancestor ofgrandparent— again, at any point up the DOM hierarchy. It finds one and styles the element accordingly.

This is not the case in Sass, which compiles to this:

.grandparent .parent .child {}

The HTML above is not styled, because the element classes don’t follow a strict grandparent, parent, and child order.

Finally, Sass uses string replacement, so declarations such as the following are valid and match any element with an outer-space class:

.outer {

&-space { color: black; }

}

Native CSS ignores the &-space selector.

Do You Still Require a CSS Preprocessor?

In the short term, your existing CSS preprocessor remains essential. Native nesting is not supported in Firefox or Chrome/Safari-based browsers, which have not received updates in a few months.

The Sass development team has announced they will support native CSS nesting in .css files and output the code as is. They will continue to compile nested SCSS code as before to avoid breaking existing codebases, but will start to emit :is() selectors when global browser support reaches 98%.

I suspect preprocessors such as PostCSS plugins will expand nested code for now but remove the feature as browser support becomes more widespread.

Of course, there are other good reasons to use a preprocessor — such as bundling partials into a single file and minifying code. But if nesting is the only feature you require, you could certainly consider native CSS for smaller projects.

Summary

CSS nesting is one of the most useful and practical preprocessor features. The browser vendors worked hard to create a native CSS version which is similar enough to please web developers. There are subtle differences, though, and you may encounter unusual specificity issues with (overly) complex selectors, but few codebases will require a radical overhaul.

Native nesting may make you reconsider your need for a CSS preprocessor, but they continue to offer other benefits. Sass and similar tools remain an essential part of most developer toolkits.

To delve more into native CSS nesting, check out the W3C CSS Nesting Specification.